Cutthroat race to university

Recent lawsuits present controversy about affirmative action, tying cheating to competitive college admissions process

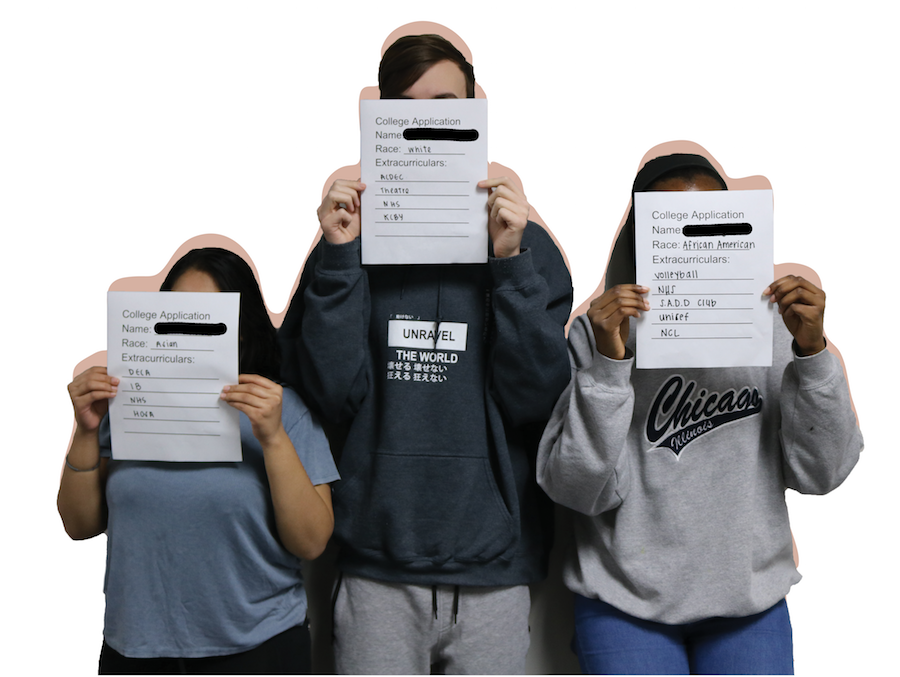

In August, President Donald Trump’s administration’s announcement to investigate a 2015 complaint against Harvard University by 64 Asian-Americans reopened the debate about the role of race in college admissions. Especially with public institutions receiving tens of thousands of applications, specific information about race and extracurriculars on resumes are not verified by college admission officials.

For five months, the college application process has been on Coppell High School senior Maya Garg’s mind. It was initially the daunting process of inputting personal information, writing a personal essay and supplements, and submitting financial aid documents for more than 20 schools, now, it was the months long wait.

Despite her academics and resume, at a highly selective, private school that she has applied to, the deciding factor in gaining admission could be out of his control: her race.

Private institutions in the United States do not have to abide by affirmative action laws unless they are given federal funding.

With President Donald Trump’s administration’s announcement to investigate a 2015 complaint against Harvard University by 64 Asian-Americans, the debate about the role of race in college admissions was reopened in August 2017.

Rise of dishonesty

Competition is said to breed excellence, however, the cutthroat culture of the U.S. college admissions process, for some, has instead given rise to desperation.

“It’s understandable to why they would it, but don’t rely on race to get you into college,” Garg said. “Be true to who you are and let the college accept you for yourself.”

The Common Application, which is used by more than 700 colleges, asks optional demographic questions about religious preference, Hispanic or Latino descent and the question, “regardless of your answer to the prior question, please indicate how you identify yourself (Select one or more).”

However, ethnic descent can also be determined by the information about where the applicant’s parents attended college and were born. First generation status is also determined this way.

Race is commonly defined as unitary, often socially imposed and it is determined by physical features. However, someone can claim multiple ethnic affiliations according to PBS. This begs the question, who determines the validity of one’s claim to a race?

In many ways, the definition of ethnicity is more flexible because it encompasses culture, traditions and features of social and cultural groups while race is determined by biology, for example, white, black or brown.

Public institutions, by law, cannot discriminate based on race, sex, age or any biological information, often with the tens of thousands of application, this information is not verified by the university’s admission office allowing applicants to exaggerate facts about their heritage to gain an advantage.

“We just go off of what was checked on the application,” Ohio State counselor David Wallace said. “It doesn’t have any sort of admission consideration, it’s just for statistical information.”

Most notably, affirmative action was implemented to lessen the historical impact of racial discrimination and is targeted at people of African-American, Hispanic and Native American descent.

According to Coppell High School lead counselor Debbie Fruithandler, she is required to verify race for the College Board’s National Hispanic Recognition Program (NHRP) by checking the student’s birth certificate and signing off on the claim.

“I’m not certain that they have a means to validate the race the student reports on their application, however, if a student is ever found to have lied on an application that might revoke their admissions or even, I guess, they technically have the right to remove you from that university, “ Fruithandler said. “I’m not sure they will do that based on that one factor.”

In order to qualify for the program, a student must be at least 25 percent of Hispanic or Latino descent.

While university admission officers are able to meticulously check quantitative data and official records such as letters of recommendation, transcripts, birth records, standardized test scores and GPA, it is more difficult to verify qualitative information.

Most commonly, officers will check for inconsistencies between the student’s resume and counselor’s letter of recommendation. With the recent cases of dishonesty, officers will most commonly, contact high school counselors to confirm claims.

However, Fruithandler said a college has never called the CHS counselors department to verify information.

Competition across the board

The sentiment of increased competitiveness has been felt by college applicants of all backgrounds and races.

Among top-tier public and private liberal arts institutions, the number of applications has increased by one third during the last five years.

Similarly, the number of high school graduates has reached 3.6 million in 2018 and almost two thirds of all high school graduates now apply to college.

However, class sizes have increased minimally despite increases in the number of applicants.

Attributed to the intentions of selective institutions to strive to build a well-rounded class size, admissions offices employ a holistic review, taking into account activities, academic records, employment history, internship experience, volunteer service and even race and sexual orientation.

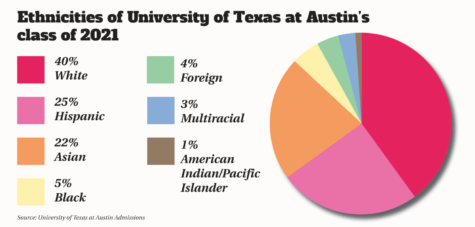

For many schools, such as the University of Texas at Austin, which receives a high volume of applicants, admissions offices rarely have the time to fact check the information on submitted resumes.

“We like to believe that students are telling the truth,” University of Texas at Austin assistant director of admissions Alexandra Taylor said.

However, at times, if something piques an admission officer’s interest, he or she will often do a quick internet search.

Lying on applications also includes parents or businesses such as buyessays.us, writing admissions essays or personal statements such in the case of tutor Lacy Crawford in 2013.

“At some point, each student is responsible for their own honor, even in the National Honor Society,” CHS AP U.S. History teacher and NHS sponsor Kevin Casey said.

Reversing discrimination

While Taylor’s job entails regular interaction with affirmative action, she also has a personal connection to the legislature.

“I, for example, was a first-generation student, my mother is from Mexico so that’s a big part of who I am and how I was raised and the language I grew up speaking as opposed to the language I engaged more within school,” Taylor said.

Taylor believes that the intentions of affirmative action contribute to a well-rounded class and the admissions office strives to include and highlight the unique opportunities, backgrounds, upbringings, cultures and religions of their world in their class.

“By employing our holistic review process not only do we feel it to be the most fair because that way we are looking at students in their individual contexts,” Taylor said.

Of about the 20.8 million of people enrolled in postsecondary institutions last year, 58 percent were white, 15 percent were black and 17 percent were Hispanic.

Affirmative action was signed into law by United States President John F. Kennedy with the intent to “end and correct the effects of a specific form of discrimination” and emerged from debates about the non-discriminatory policies in the 1940s as part of the Civil Rights Movement.

“A negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the state of which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing a high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day, one third as much chance of completing college,” Kennedy said in his address to the nation.

With a focus on education and employment, affirmative action grants special considerations to historically excluded groups such as racial minorities including Native Americans, African-Americans, Hispanics and women.

“It’s this recognition that sometimes these inherent facts about us very much say who we are and the experiences that we have had,” Taylor said.

At UT, Taylor oversees the holistic review process and recruitment efforts and claims that race and ethnicity is mainly looked at an individual level and the class simply comes together.

While the practice of affirmative action is constitutional, the use of racial or gender quotas by employers or universities is not.

“Shouldn’t college admissions be determined by merit?” CHS economics and psychology teacher Jared Stansel said. “Not on where you’re from or the color of your skin? If we have to correct for historical discrimination as individual human beings, we are not going to see everything eye to eye.”

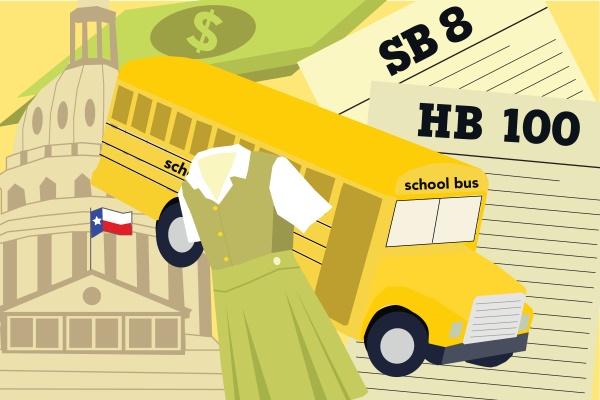

Current controversy

Edward Blum rose to prominence by helping file over two dozen lawsuits challenging affirmative action policies and voting rights laws.

In June 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that schools could continue using race as a factor in college admissions. The case was filed by University of Texas at Austin applicant Abigail Fisher in 2008.

Fisher, a white woman, contended that she was denied admission to the university over peers with lower scores, extracurriculars and grades because of the color of her skin.

“Like most Americans, I don’t believe students should be treated differently based on their race,” Fisher said after a court hearing. “Hopefully, this case will end racial classifications and preferences in admissions at the University of Texas.”

Eight states have a current ban, passed through voter referenda, against race-based affirmative action at public universities: California, Washington, Michigan, Nebraska, Arizona and Oklahoma.

Other states still practicing affirmative actions have promised new diversity strategies such as percent plans, adding socioeconomic factors to admissions, increasing financial aid packages, improving recruitment and eliminating benefits of legacy applications.

“Who gets to determine whose disenfranchisement has more merit or is more legitimate?” Stansel said.”It’s nice and pretty and it sounds like we are trying to do the good thing but usually, the path to hell is paved with the best intentions.”

After allegations of racial discrimination in two federal cases, Harvard University issued a statement.

“To become leaders in our diverse society, students must have the ability to work with people from different backgrounds, life experiences and perspectives,” the university said in a statement. “Harvard remains committed to enrolling diverse classes of students. Harvard’s admissions process considers each applicant as a whole person, and we review many factors, consistent with the legal standards established by the U.S. Supreme Court.”

“I have grave concerns about anyone who would falsify information on an application or a resume because it really speaks to the character of that individual and in life,” Fruithandler said. “Our character and our integrity are of the utmost importance and at some point, not living up to those standards, will catch up with that student.”

Tanya Raghu is a senior and third year staffer on The Sidekick. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with friends and family, watching movies and...

Wren is a senior. She moved here from the Land of Disney: Orlando, Florida. Yes, she went to Disney a lot. Yes, she has been to Universal. Wren adores...