Feminism as a living entity

Women’s rights movement evolving over time

February 16, 2019

DALLAS – Clutching a sign featuring a photo of Christine Blasey Ford, and beside it the words: “Of course I believe her, the same thing happened to me”, Dallas resident Amy Bennett stomped through the city for the 2019 Dallas Women’s March.

“I just want to make sure for myself, for my daughters and for every woman in America that we have equal rights and that we continue to progress forward,” Bennett said. “It’s wonderful to see we’re not alone. There’s women who will believe us, women who are fighting for us, because we can’t do it by ourselves. We need other people to stand with us, to believe us, to march with us, to vote with us.”

We need other people to stand with us, to believe us, to march with us, to vote with us.

— Amy Bennett

At age 15, Bennett experienced an attempted rape, but fear of disbelief kept her from speaking up until recently, when the #MeToo movement gave her the courage to finally tell her story. Largely because of the statute of limitations, which prevents people from being prosecuted after a certain amount of time has passed since the crime, her attacker was never punished.

“I’ve seen so much forward progress [regarding feminism],” Bennet said. “For example, now women are more vocal than we used to be – the #MeToo movement is one example, the Women’s March is another example.”

In addition to becoming more vocal, throughout the past few decades the feminist movement has evolved in numerous other aspects, proving itself to be a living entity that will adapt to each generation’s needs. The fight did not end when women were granted the right to vote, the right to initiate a divorce, or the right to run their own bank accounts.

“Women have won voting rights, and things like that, so some people think there’s nothing left to advocate for,” Dallas Women’s March attendee Hayley Scoggins said. “But that’s not true. Helping women of color is one thing, and there’s multiple others.”

Uniting with fellow equality campaigns

To intersectional feminists, one group’s battle is every group’s battle.

From welcoming all sexualties to accepting all ethnicities, intersectional feminists fight for the complete, multi-faceted sphere of equality, rather than picking bits and pieces to support. In recent years, the movement overall has been moving toward this principle.

“In the end, equality in general is what we’re all striving for,” Coppell High School sophomore Jordyn Morris said. “It’s very important for the equal rights movements to support each other. We’re all humans, we all deserve the same rights.”

The 2019 Dallas Women’s March reflected this ideology by being a melting pot of diversity; after marchers reached Dallas City Hall, speakers from a multitude of equality movements took the stage.

“I want to remind everyone that Texas locks up more people with mental health conditions than many other states,” speaker Natasha Taylor said. “We need to make a difference. Many of the people who are poor and experiencing homelessness have a disability.”

Advocates marched for the acceptance of all genders, all races, all lifestyles.

They marched for attendee Jade Voyles, who was born with a spine-related disability, and participated in the event via wheelchair.

“I get a lot of stares and mean looks [because of my disability],” Voyles said. “[I came to the march] because there’s a lot of injustice for women, especially for people like me. I know that I’m not alone, seeing the women around me.”

They marched for Muslim attendee Maysa*, who is regularly made uncomfortable because of her religion, and was dressed in bloody white robes at the march to raise awareness for Razan Al Najjar, a Palestinian martyr killed by the Israeli military.

“On a day to day basis, I am regularly made uncomfortable due to the Palestine aspect of my identity, or the Muslim one, or both, so this is something that is awesome to be able to fight for,” Maysa said.

They marched for attendee Julia Johnson, a transgender woman who came out two years ago.

“When I go places, people treat me differently because they notice I’m transgender,” Johnson said. “They look at me differently, like I’m a freak of nature.”

After being disappointed in their lack of representation during last year’s march, the American Indian Heritage day in Texas organizers spearheaded this year’s by physically leading the march and bringing their culture’s dancers to the event.

One of the organization’s ambassadors, Jodi Yellowfish, grew up in the Dallas area rather than a reservation, and was the only American Indian at her school, where she was teased for her culture.

“[The discrimination American Indians face] is almost like an inherent thing,” Yellowfish said. “It’s just something I feel everyday, all day.”

The natives’ opportunity to lead the march provided them a platform from which to raise awareness for their Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), as the murder rate for Native American women is 10 times the average, and four out of five native women are somehow troubled by violence.

“I came to support my sisters and the missing women and children,” Native American Jason Ortiz said. “[Seeing my people lead the march] brought a lot of pride to me, it’s good to see that acknowledgment. Many times, our voice is overlooked. When you have a table, and you have all these individuals that sit at the table, we just want to sit at the table to, so people can hear our voice.”

Because many equality advocates consider themselves intersectional feminists, they were angered by the revelation that a few of the national Women’s March founders were found to support anti-Semitism and homophobia. Angered enough that some, including Morris, refused to attend the march.

“I got really upset [about the founder controversy] because I am part of the LGBTQ community, I have friends who are part of it, and I have Jewish friends,” Morris said. “I decided that was something I didn’t want to support.”

Pushing for women in government, male dominated industries

While early feminists were fighting to simply give women the right to vote, current advocates are taking the issue to the next level, pushing for more women to be the ones others vote for.

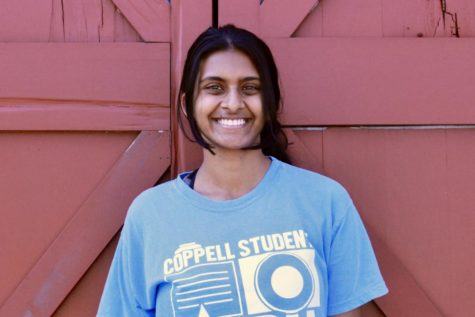

“If you see pictures of any political scene, if you take the men out it’s always a scary picture because there’s only a few women,” CHS senior Arohi Srivastav said. “That’s not OK, because we’re half the world, and our voices need to be heard too.”

Last November, the portion of women in Congress hit a record high at 20.6 percent – still well below half – with 23 women in the U.S. Senate and 87 in the U.S. House of Representatives. Likewise, the number of women who even ran also set a record last year, with a total of 256 women qualifying for the November 2018 ballot across both houses.

“Even when a women runs, it’s making a statement because that has only started in the past few years,” Morris said. “When they run, it’s them saying, ‘just because I’m a woman doesn’t mean I can’t do this. I’m a citizen of the U.S., I can do this.’”

During the Revolutionary War, one of the colonists’ main complaints was their lack of voice in government, despite the fact British laws still affected them. Because many laws specifically affect women more than men, many feminists think an increased female voice in government is constitutionally crucial.

“In office, when making laws about abortion, yes men can have a say in it, but for only men to decide what should be done with women’s’ bodies, without women having much say in it, is absolutely not OK,” Srivastav said.

According to Srivastav and other intersectional feminists, the same principle applies to people of color, LGBT citizens and other minorities, which is why vast diversity in Congress is one of the movement’s priorities. The world’s first native and muslim Congress women — Deb Haaland, Sharice Davids, Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar — being elected last year was an important victory for feminists and other equality advocates.

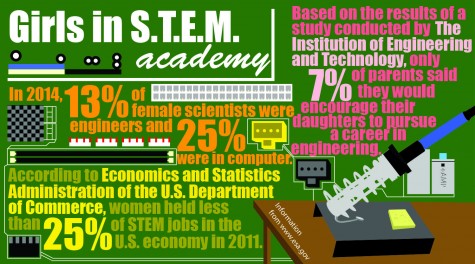

Politics is not the only field feminists are pushing more women to enter. From STEM to film, fighting for females to break into traditionally male-dominated industries is one of modern feminism’s main goals – a major step up from the early feminists’ goal of getting women out of the kitchen and into any job at all.

“My friend in engineering is the only girl in her class,” Morris said. “Women have always been pushed away from those industries, so if you see women in those industries, it’s really powerful to see them there.”

Scoggins first discovered her passion for feminism around age 20, when she realized the discrimination girls in her field of study face.

“[My intended field] is a really male dominated industry, and it’s really hard to be taken seriously as a woman who has opinions, musical opinions,” Scoggins said. “In my music school, there was a doctoral student who was always given the lower choirs; whenever she got accepted, she demanded that she wanted to have one of the top choirs, and they didn’t necessarily like that – it was all men who were on the board, by the way. If she was a man, it would be different, he would be seen as really driven and motivated.”

From the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, which is considered to mark the beginning of feminism, to the 2019 Women’s March, the movement has evolved and molded itself to address each generation’s needs.

The future of feminism

A few years, decades or centuries from now, it is likely that women’s voice in government will equal men’s, that there will be few industries still considered “male dominated”.

“In terms of legislation, I think we’ll have laws [for equality], and in theory, we’ll probably all be equal,” Srivastav said. “But I think equality also resides in people’s minds and how we view each other. We’re never gonna reach the point where 100 percent, every single person, sees everyone as their equal. We can get close to that, though.”

But according to Srivastav, even if feminism’s current goals are accomplished, the movement will not die.

“I don’t think feminism will end after equality is legally reached,” Srivastav said. “Feminism is not just about politically seeing men and women as equal, it’s also about the empowerment and upliftment of women on a day-to-day basis. And I don’t think that’s ever something that’s just going to go away.”

Follow Pramika on Twitter @pramika_kadari