Molding to the new normal

Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on education

After returning to full in person school, Coppell High School students have been facing academic and emotional challenges. Coppell ISD is working to bridge learning gaps caused by COVID-19 by emphasizing learner choice and interaction.

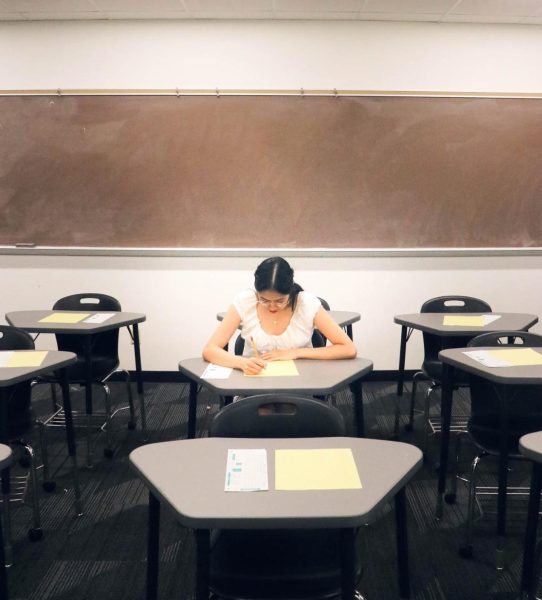

For many Coppell ISD students, the 2020-21 school year began in the silence of their bedrooms in front of a screen. Fast forward, and the school year finished in the same place, with only a screen to connect them to buildings and teachers they barely knew.

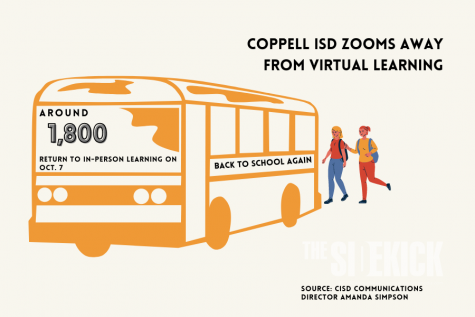

The 2021-22 school year opened in person for grades seven through 12, with a virtual option available the first nine weeks only for kindergarten through sixth grade. But amid the joyful reunions, the impact of last year was festering. How do you learn in a building with others after 18 months of doing almost the opposite?

“You got sidetracked a lot last year,” Coppell High School sophomore Ayman Salaar said. “You had different [distractions], whereas being in school, you don’t have those worries.”

CHS Principal Laura Springer’s priority is to bring students back into the routine of school.

“Last year, you could go online, you could wake up at any time of the day you wanted,” Springer said. “Our students for 18 months got trained to not have demands and a time limit [put on them]. We feel like the big gap right now is just teaching kids to get a schedule again, to teach kids to understand there are deadlines they have to meet, and those deadlines are going to be before 11 or 12 at night.”

The emphasis on establishing routine was why CISD classrooms dedicated the first week of school to building connections, reserving curriculum content for the weeks that followed.

“We were very intentional about spending that first week of instruction, primarily, building relationships and getting a feel for where everyone is in their headspace,” CISD executive director of teaching and learning Dr. Deana Dynis said. “That was time well spent. Curriculum wasn’t yet a priority. We just [wanted] to make sure that we are building the most levels of support that our learners need coming back into a more structured environment.”

Once the first week was finished, however, teachers began seeing gaps in students’ understanding of the curriculum. CHS geometry teacher Philip Smith attributes this in part to the virtual environment last school year, where many students fell behind in the curriculum due to cheating or a lack of understanding.

“My on-level students, their algebra skills are very poor,” Smith said. “I would say most of them are at an eighth grade level, instead of at a 10th grade level. One hundred percent the reason why is because of last year. Some students are great at algebra and that’s because they actually tried to learn it last year, and then there were a lot of students who either couldn’t learn virtually or chose not to and just cheated throughout the entire year.”

One method through which teachers are mending these gaps is by providing learners different ways to showcase their knowledge, which gives them the option of meeting curriculum standards in a multitude of ways.

“Our campus is embarking on Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which allows choice in the process,” CHS associate principal Melissa Arnold said. “[It] allows you the opportunity to say, ‘Yes, I can show you that I understand this standard by taking this multiple choice test, but I would much rather show you that I’m mastering this standard by writing an essay or by creating an art project that covers the same thing.’”

In Smith’s classroom, UDL takes place through a system involving self-tracking and reflection and group learning. Assessments, which include tests and projects, do not receive number grades until the student shows corrections and/or reflection. At the end of the nine week grading period, students have the opportunity to discuss a potential five point raise in their grade after presenting evidence as to why to Smith. The self-tracking, group learning and grading policy directly correspond to four levels of understanding, with level one beginning at being able to identify and recognize the topic and level four ending with being able to verify, prove, teach and create content related to the topic. This system relies heavily on face to face interaction and conversation, which many students lacked last year.

“Having conversations from person to person, compared to teacher to student, is huge because it deepens the relationship between me and the student,” Smith said. “I don’t always think that grades accurately reflect someone’s knowledge. I came to the decision last year that it would be a good idea to have the students argue in a positive way. I told them at the beginning of the year that there were multiple different ways you could convince me. One of the ways is every class period I have my students track their learning – what they do, what was the topic that day, did they take notes [and] did they complete their practice. I have dived into this whole thing about level of understanding versus grades.”

For Smith, this system has proven to be relatively successful academically and has also helped to reduce stress among his students.

“It’s been really helpful,” CHS sophomore Carleigh Fezzey said. “It was something that we all needed because a lot of people were virtual. It’s been really helpful to have a teacher who wants you to get to that deepest level of understanding to be able to do the work on your own.”

Other examples of UDL in CHS include standards-based grading, pioneered by IB mathematics/AP calculus BC teacher Ian VanderSchee in 2019, in which students are graded by their mastery of the curriculum standards instead of scores on assessments. Standards-based grading is also utilized by CHS AP calculus BC and honors precalculus teacher Dana DeLoach and AP chemistry teacher Amy Snyder.

We want to help our kids but our kids have to help us help themselves. — Laura Springer

“[Standards-based grading] helps me focus more on content rather than what grade I’m going to get,” CHS IB senior Una Urgello said. “One of the first tests I took [this year] I did really bad [on] but it didn’t affect my grade that much. It put me at ease, and it just helped me focus more on what I should get better at. ”

An additional benefit of utilizing UDL in classrooms is that it is centered around more qualitative practices. Several academic assessments in the 2020-21 school year, including the STAAR (on the elementary and middle school level) and the SAT and ACT were optional for fall 2022 enrollment. The data from these examinations were used to help determine where students were academically and how to convey the curriculum for maximum understanding.

However, with these tests becoming optional, some data is missing.

“We have the data from the learners who took the tests, but we’re missing a whole section of learners who opted out and chose not to take the tests,” Dr. Dynis said. “It’s an interesting challenge from a data standpoint. There are a lot of things that I believe our learners learned out of sheer necessity over the last year that we may not have learned otherwise. A lot of that is qualitative in nature, not just quantitative, and we always knew that the quantitative didn’t paint the whole picture. This has taken an evolutionary leap forward in terms of thinking about learning anytime, anywhere, any space. COVID provided that for us. I don’t think we’ll ever go back to what’s normal.”

Qualitative data from classrooms can also be supported by Professional Learning Communities (PLC), which are well established in CISD. PLCs are content groups in which educators gather to discuss how to better deliver curriculum. According to Dr. Dynis, PLCs are centered around four concepts: what students need to know (standards), how educators can know if the students understand the content (assessment), what to do if the students do not know the content (intervention) and what to do once the students already know it.

Through PLCs, educators may alter the sequence of the curriculum, but not its scope.

“The sequence that the school district sets is fairly flexible,” Dr. Dynis said. “We can revise the order in which we teach something to best meet the needs of our learners. The scope of the curriculum is defined by the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills [TEKS]; it says, ‘This is what you have to teach.’”

Springer thinks for UDL, choice-based learning and the return-to-school to be smooth, students must apply themselves and respond to the school environment.

“I really want to tell our kids, ‘You’ve got to get involved again in the system [and] with our teachers, you’ve got to get involved with the learning and you’ve got to apply yourself,’” Springer said. “We’re going to present work and learning. We’re going to present critical thinking and design, but [students] have got to put [their] heart and soul into that and give back to us so we can meet [them] halfway and help get [them] to be successful. Right now it seems like we’re doing all the pushing and there’s no give back. We want to help our kids but our kids have to help us help themselves.”

Follow Akhila (@akhila_gunturu) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.

Akhila is a senior and the Executive News Editor for The Sidekick. She is part of the IB Diploma Programme at CHS and when she isn't doing schoolwork,...

Srihari Yechangunja is a senior and the Executive Design/Interactive Editor for The Sidekick. In his free time, Srihari enjoys producing YouTube videos...

Nandini is a senior and the photo editor for The Sidekick. She is in the Coppell Color Guard, and outside of school she enjoys doing Taekwondo, dance,...