Mapping COVID-19: adopting manual, technological means of contact tracing

December 1, 2020

One positive case.

One student, walking the carpeted halls of Coppell High School, sitting down for lunch and going home to siblings and parents.

One student, unwittingly spreading the virus that has affected the life of every single person around the world.

The next day, an email arrives in the inbox of every high school student and parent in the district: ‘Notification of COVID-19 Positive In-Person Student at Coppell High School.’ Soon after, Coppell ISD’s COVID-19 tracker sees an uptick in positive cases.

Such is the reality of coronavirus in Coppell.

In the 2020-21 school year, pep rallies are filmed and pieced together, student athletes are unable to play due to quarantines, and every class period takes place on Zoom. When everything is virtual, how do we track what is physical? The answer lies in contact tracing. It is a practice dating back centuries in which people exposed to a disease are identified, assessed and managed to reduce transmission. However, during the coronavirus pandemic, the method – and application – of contact tracing has expanded and modernized.

Enter NOVID, the first and only completely anonymous COVID-19 radar application published in the United States. NOVID was conceptualized by Carnegie Mellon University associate professor of mathematics Dr. Po-Shen Loh.

Dr. Loh is a fellow for the Hertz Foundation, an organization which funds the post doctoral education of its members in exchange for their moral commitment to aid in a national emergency. On March 14, Dr. Loh received a message from the Hertz Foundation detailing the extent of COVID-19 and calling the recipients to action. The next day, as he began reading a Ph.D thesis one of his students had written about network theory, Dr. Loh had a pivotal realization.

“When I got to the second sentence, it just hit me like a flash,” Dr. Loh said. “COVID-19 is a network problem. Then, I started to think: what can you do with that network? I realized that in the 21st century, because of smartphones, we can use the network to fight pandemic spread in an extremely powerful way.”

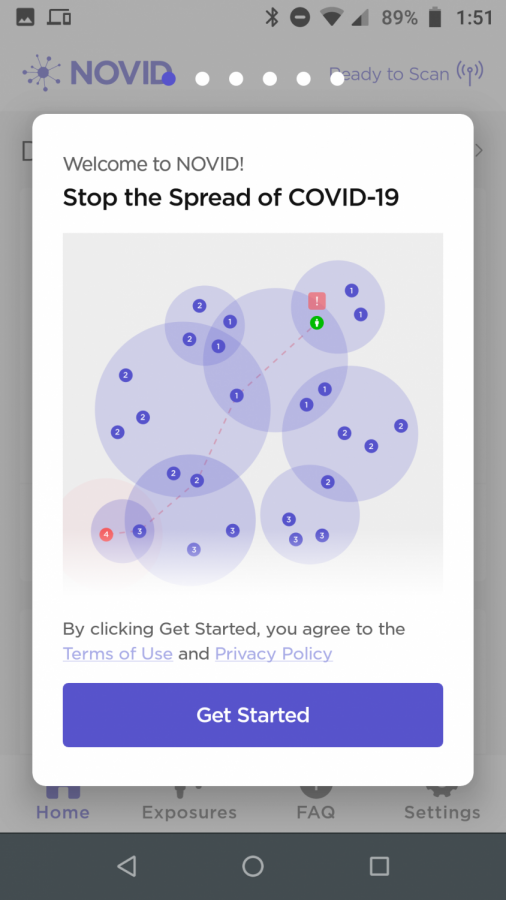

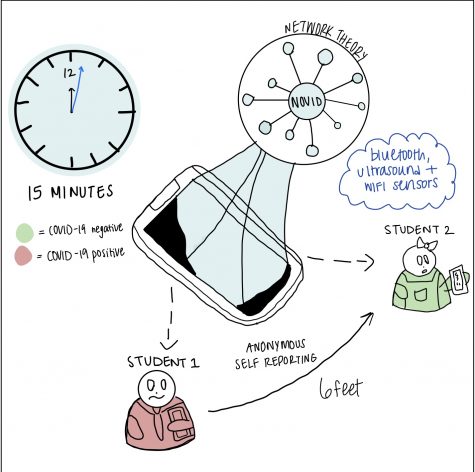

In network theory, degrees of separation measure the amount of social distance between people. For example, someone is one degree of separation away from everyone they know, two degrees of separation away from everyone their friend knows and so on. NOVID allows people to visualize cases up to 12 degrees of separation away from them by tracking and compiling these interactions graphically. Additionally, the app records the physical distance between people for each interaction, which can be reviewed and verified at later dates.

“We’re building a big network, and through it, I can understand how COVID-19 is moving from person to person,” Dr. Loh said. “This is really useful information because we need to use science to inform our policies. So, if you think about it, it’s pretty scary that we don’t yet have that information. Everyone is governing blind.”

Using bluetooth, ultrasound and WiFi sensors on smartphones, NOVID detects other devices with the app downloaded, without the app even being open. However, the app will only detect these devices if they remain six feet apart or closer for 15 minutes or more. The app is checking for prolonged exposure, meaning the two users have a higher risk of transmission.

When a user is exposed to someone with the virus, NOVID notifies them with information about how long and at what distance the user interacted with the person who had the positive test. With the capability to understand how far away each positive case is from the user in terms of networks, NOVID becomes a precautionary tool that can show the virus moving degrees towards or away from an individual.

“NOVID helps you avoid getting quarantined,” Dr. Loh said. “You see it coming, and then you do something about it. You make sure you’re wearing a mask; you avoid unnecessary gatherings. It’s going to have as big of an impact on controlling pandemics as the invention of radar and sonar in modern warfare. It gives you the power back.”

NOVID’s design allows it to fill gaps in large communities by pinpointing individuals who may have been close enough to be exposed to COVID-19 but are unknown to the individual with a positive test result. These strangers may otherwise be unaccounted for in manual contact tracing.

Once Dr. Loh made the connection between contact tracing and network theory, he began researching if smartphones could be used to build these networks without utilizing users’ personal information. Privacy has risen as a concern because countries including Israel, Singapore and China began using a combination of location data, video footage and credit card information to conduct contact tracing in their populations.

However, unlike other contact tracing apps, NOVID does not require any personal information, including phone numbers, addresses, credit card information and email addresses.

“[Other apps] don’t mind about the regulations because they’re taking the personal information and selling it,” Dr. Loh said. “If we tried to do this 10 years ago, the only way would have been to get everyone’s GPS. But if I have your GPS information, I have too much information. Our entire app works by checking if two things are relatively close to each other, analogously to how we use bluetooth to connect two earbuds.”

With the help of dozens of CMU students and alumni, Dr. Loh’s initial idea became a fully-functioning app available for iOS and Android. NOVID is being used at CMU and Georgia Tech University.

Currently, the NOVID team is finding new ways to use sensors, particularly in iPhones. Dr. Loh is investigating how WiFi networks work in schools and universities to better understand how WiFi sensors can be utilized with the app in those settings.

“I did it because I didn’t see anyone else doing it, and that’s why I still work on it,” Dr. Loh said. “At this moment, I do not know of any project in the entire world except a vaccine which will do anything. I cannot name a single thing – and that’s why everyone is either despondent or has given up.”

NOVID was pitched to CISD in early August, a connection that was facilitated by CHS 2018 graduate and current Johns Hopkins University sophomore Deepa Ravindra. Ravindra is one of NOVID’s campus ambassadors, who coordinates with administration at universities and school systems they’re associated with to bring awareness to and implement NOVID. With two siblings currently in CISD – Mockingbird Elementary fourth grader Rajiv Ravindra and CHS senior Divya Ravindra – beginning the school year virtually alongside her, Deepa saw an opportunity to introduce NOVID to the same district she grew up in.

“I was hearing about CISD reopening [when I was home for] the summer, so it was something on my mind,” Deepa said. “Everyone in CISD, for the most part, is provided a technological device that they keep with them and I thought that it would be very useful to have this in place. I thought the landscape and design of CISD would very much align with what NOVID has to offer and that it was worth pitching to the district.”

For Dr. Loh and the NOVID team, CISD was a worthy target because of the possibility of integrating the app throughout Coppell. Effective contact tracing requires speed and high adoption. The digital aspect can ensure greater speed in the identification and management of cases, but high adoption means that many people need to download the app. With more downloads, NOVID detects a greater number of smartphones nearby and builds a more accurate and useful network to track transmission.

“The biggest impact is if everyone gets on the app and their families are also encouraged to get on the app,” Dr. Loh said. “This is something that could have a huge impact with a city-wide deployment. The sooner we can have something deployed in the school district, town and city, the better off everyone will be.”

Accepting a new normal is one thing. But living in it, every single day, is another.

Students, staff and administrators go from class to class: clicking into Zoom meetings and walking the spacious halls of CISD schools. Teachers prepare virtual activities and greet students with grins hidden behind masks, even clapping and dancing on Friday mornings.

During it all, classrooms are emptied, entire athletics teams are quarantined and COVID-19 notification emails pile in inboxes. The school year is progressing – but there is still a virus that needs to be contained.

Behind the brunt of this effort is a team of four people. These individuals answer phone calls daily and work with all 18 CISD campuses and communicate with families. The group, expanded from only two people at the start of the school year, leads manual contact tracing for a district with more than 13,000 students.

NOVID was pitched to a member of this committee, CISD Executive Director of Communications and Community Engagement Angela Brown, prior to the start of the 2020-21 school year. According to Brown, the district does not believe that a K-12 environment would be a good fit for NOVID. The main arguments against the implementation of the COVID-19 radar app are privacy laws, an extensive enforcement process and desire to maintain manual contact tracing.

“We are dealing with minors and their medical rights, so we have to be very careful with anything that might track a student or release any information,” Brown said. “If we push it out to all iPads, we would have to get students and parents and families on board with using it. We would have to train them, we would have to explain it. We really wanted to concentrate on implementing safety protocols to keep our students safe.”

Additionally, Brown thinks there are specific advantages to having a person conduct the assessment portion of the manual contact tracing process. By gleaning specific information about a confirmed case’s interactions, people may more effectively understand how and at what point the virus was transmitted.

“A lot of the work when it comes to contact tracing does have to be by a human, because you have to ask them very specific questions,” Brown said. “Did you touch anybody, did you hug anyone, were you within six feet for 15 minutes? [An app] is not going to know if you touched someone, if you hugged somebody, if you were sneezed on or coughed on.”

It is these questions that CHS nurse Beth Dorn asks students and families daily. At the largest school in Coppell, Dorn’s workspace and routine look a bit different. In a typical year, the nurse’s office averages 70-80 visits per day, at times reaching 100. This school year, however, Dorn sees at most 15-20 students per day. The nurse’s office has expanded into the Student Resource Officers’ space with clearly defined ‘sick’ and ‘well’ areas.

These transformations, as well as mandates for teachers to send only students requiring medication or examination to the nurse, ensure a reduction in traffic and hopefully transmission. Instead of student interaction and evaluation, much of Dorn’s work now involves updating a COVID-19 tracker with student names and quarantine dates by conducting interviews with families.

“My job has changed tremendously because I spend a lot of time on the tracker and calling and talking to parents,” Dorn said. “Sometimes, it’s just so many phone calls and emails, and then it tapers off – you just never know what’s going to happen. The numbers we’ve seen on certain days have been overwhelming.”

When a student comes to her office, Dorn takes their temperature and asks about their complaints. She directs them to the ‘sick’ area if they seem to be exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19. After Dorn is informed by email or visit of a student exposed to COVID-19, the first step is tracking the duration and extent of their symptoms.

“People are more on guard and cautious than they typically might be,” Dorn said. “I have had quite a few kids coming in here saying, ‘Oh, I just don’t feel quite right, I better go to the clinic.’ People used to say, ‘Oh, I don’t want to miss school, I think I’m going to stay here even though I don’t feel good.’ I don’t think we’re seeing that at all this year.”

If the student tests positive, the CHS administration team must remove them from in-person classes and bring them to the nurse’s office. The student’s parents are informed by administrators and instructed to pick up the student as soon as possible. Then, the administrators determine when and where the student was on campus two to three days prior to having symptoms from video footage and other evidence.

In the case a student who tests positive also has siblings at other CISD schools, it is Dorn’s job to communicate with nurses at the respective elementary or middle school to ensure all students are quarantined.

CHS senior Ananya Chawla is a hybrid student, where she attends her practicum class in-person every school day. A quiet campus greets her as she walks through the front entrance and empty hallways.

“It’s a strange experience,” Chawla said. “I’m one of the only people coming to school for third period. Usually I come in before the bell rings to let students out, so it’s very quiet and I typically only see a few administrators around.”

The week prior to Thanksgiving break, Chawla’s class had to shift to a virtual setting due to a positive COVID-19 case, which had a significant impact on class activities.

“It was inconvenient because a big part of our class involves hands on training, labs and skills which are taught by instructors from Brookhaven College,” Chawla said. “We didn’t really have the resources to suddenly shift online and so we had to cancel those hands-on activities.”

Though Chawla is not currently doing in-person learning, her mindset on in-person learning has shifted due to rising coronavirus cases.

“It didn’t make me nervous [to go to school] at first, because I trusted my classroom,” Chawla said. “I am in a classroom full of CPR-certified learners and a teacher who is a certified paramedic, so I felt safe in that environment. But right now, with all the cases, it does make me a little nervous to be around people.”

Above all, the manual contact tracing process requires collaboration on the part of multiple CHS departments. CHS clinic aide Jane Signore works with Dorn to enter symptoms and quarantine dates for individuals. CHS registrar Kristi Carroll is informed as soon as the student tests positive so she can transfer them from in-person to virtual school, if applicable, which also allows the teachers to become aware of the change. Afterwards, CHS administrative assistants Veena Bhat and Kim Dicken prepare letters with quarantine information and dates to the respective families of any exposed students.

“Despite all of it, it’s been almost a bonding experience,” Dorn said. “The admin teams, nurses, and registrars – we’re working a lot closer than we normally do.”

In the spring, the necessity of ‘flattening the curve’ was emphasized. Now, as the curve continues to surge and dip and the fall semester comes to a close, the landscape of CISD and the lives of its students and staff continues to stray further from what was considered normal. But, behind the emails, trackers, newsletters and rumors lies CISD’s core. It is one of collaboration – across campuses, administrations, staff and families – and a commitment to streamlining and maintaining tracking of the virus until each campus can function as they once did.

Follow Shivi (@_shivisharma_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.