Past in present

Diving into determination process of U.S. history curriculum

Coppell Middle School East eighth grader Justin Sturm, sixth grader Mallory Cooper and Coppell High School junior Granger Hassmann read various history books. The current U.S. history curriculum in Texas is determined in a process that involves lawmakers, educators, parents, students and industry representatives.

“‘It’s today in history!’”

This is Wilson Elementary fifth grade teacher Beth Brandenburg’s first year of teaching history in fifth grade after 19 years of teaching, 15 of those spent at Wilson.

“This year it’s been really exciting,” Brandenburg said. “So many things that happen in history are events that are [pertinent to] today, and the kids need to know about that. To me as a teacher, to be able to give two sides to the story is really important because the learner needs to learn how to develop real opinions about things and know the facts behind how things are happening.”

Elementary school lays the foundations for higher level U.S. history education. According to the Grade 5 Social Studies Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS), learners are expected to explore a survey of U.S. history from 1565 to present, with a focus on introducing historical content, geography, economics, government, culture and social studies skills, such as differentiating between valid primary and secondary sources and mapping geographic information.

“Fifth grade is a great year to start getting your feet wet into social studies,” Coppell Middle School West eighth grade U.S. history teacher Margaret Anne Tucker said. “It gives them a very good introductory perspective; they get a great cursory exploration of what we cover more in eighth grade. I like that we stair step in that way.”

But how exactly is this introductory curriculum determined?

The State Board of Education (SBOE) determines policies and standards for Texas public schools, which includes establishing social studies curriculum standards, adopting instructional material and determining graduation requirements. The SBOE consists of 15 members who are elected by the public to represent their districts. Representing Dallas (District 13) is Aicha Davis, who also serves on the Committee on Instruction.

The SBOE is split into three primary committees, with the occasional Ad Hoc committee, which is created to address specific issues. The Committee on Instruction’s main responsibilities include establishing curriculum and graduation requirements, instructional materials, library standards, curriculum implementation and more.

The SBOE periodically reviews and revises TEKs for each subject area by creating work groups to make recommendations, holding public hearings on recommended changes and later voting on them. These work groups consist of educators, parents, business and industry representatives and employers.

“It’s a pretty well-vetted process that is organic,” Coppell High School U.S. history teacher Diane de Waal said. “In Austin, when I served [on a work group], there were parents, teachers, professors, all parts of life.”

The last revision to the current social studies curriculum was in 2010. The curriculum was then streamlined in 2018, and is set to be revised again in 2023 to incorporate events that have taken place since the last revision. When a curriculum is streamlined, the content required is reduced to fit instructional years or before state-required assessments. Streamlining does not involve the addition of new materials; instead, it pares the curriculum down to what is essential for the time allotted to the course.

“When [the revision] process begins, I encourage both educators and learners to take part,” Coppell ISD director of social studies Maria McCoy said. “Whether it is serving on a TEKS Committee, writing letters to your SBOE member or testifying in front of the SBOE during hearings on the proposed standards, it is important to let your voice be heard.”

The SBOE derives its authority from Article 7, Section 8 of the Texas Constitution. The board is required to meet at least quarterly; the upcoming meeting is from April 14 -16 and will be livestreamed.

“Back in the day, [history education] was very black and white,” Brandenburg said. “Whenever I was growing up and you read it in a book, [that was] the way [it was]. I think certain things were kind of covered up when I was growing up, whereas things now are out in the open. It’s more real. I just want to teach more [history], so the kiddos know [what is happening].”

As children progress from elementary to middle school, they dive deeper into the metaphorical swimming pool of history.

The eighth grade U.S. history curriculum provides more depth to the knowledge established in fifth grade, with TEKS focusing on historical content from the early colonial period through Reconstruction, gaining a better understanding of economics, government and culture, applying critical thinking skills and analysis.

“[Elementary school students] have a couple of years to learn more about a global perspective and focus on Texas,” Tucker said. “We’re always circling back because it gives them a chance to compare. [In middle school], we see a lot of ‘Oh, I learned that in fifth grade but now I know how it looks in comparison to world history in Texas,’ so it bookends nicely to those middle school years where they’re really learning how to do social studies.”

Coppell students typically begin a topic in eighth grade U.S. history with an introductory activity, such as talking through notes or watching a video. The year is characterized by a development of writing skills and deeper understanding, with students focusing on primary and secondary source analysis rather than simple identification. Book studies are incorporated as well to balance between project-based learning and direct instruction.

“I would like to think that we are moving away from wholesale lectures and taking notes,” Tucker said. “We’re focusing more on turning it over to the students and providing them with good primary and secondary sources and letting them really construct their own interpretation. We do try to do a lot of vertical alignment with the high school teachers, so we’ve tried to incorporate more writing and analysis.”

At the high school level, individual research, analysis and critical thinking skills are heavily emphasized parts of history education. These are cornerstones of Advanced Placement courses and the International Baccalaureate (IB) program at CHS.

“The IB curriculum charges us with giving students the opportunity to work as professionals,” IB program coordinator Michael Brock said. “Providing those research opportunities and putting you in a position where you have to manage that yourself, that gives you the opportunity to really not just learn historical information, but also learn about how historians think.”

Unlike elementary and middle school curriculums, the IB curriculum is determined by the International Baccalaureate Organization, which designs curriculum to be broad so that individual schools can filter it to meet local standards.

“In all honesty, there are only a couple of things for which, whatever the state standards are, we don’t already meet or exceed them,” Brock said. “I have to incorporate some government concepts and principles into [IB History of the Americas] just to make sure we cover what the state says you need for that credit. But it’s very easy to do. So, there are just a handful of things we’ve got to make sure we work in, and they’re very easy to work in with the topics we choose to teach.”

Also offered at CHS are AP history courses, with AP U.S. history (APUSH) being a popular option for sophomores, juniors and seniors to meet their graduation requirements. APUSH focuses on U.S. history from 1491 to the present day while analyzing historical events and trends. The course culminates in students taking the APUSH exam in May. However, due to COVID-19, the exam was pared down significantly in May 2020, with students being assessed through a 45 minute document based question (DBQ).

“We don’t have a one size fits all,” de Waal said. “We have different learners that would benefit from different programs. U.S. history should be rich and robust and meet interest level and learning level as an AP class, IB class or dual credit. It’s important to have different fits for different kids that have different needs.”

Though each history class may contain differences in teaching style and to an extent, content, there is one similarity connecting them all: the necessity of incorporating current events into every day learning.

“We need to look more at current events,” CHS Principal Laura Springer said. “All the time frames you’re trying to cover with U.S. history are changing again, by the moment. We need to talk about everything, we need to weigh it, we need to research it, we need to look at it.”

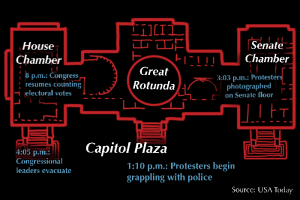

On Jan. 6, the United States Capitol was stormed as a part of several protests in reaction to the results of the 2020 presidential election. A sea of people. Five deaths. Riots. Vandalism. Shootings.

“We always have groups waiting for somebody to let them hate,” Springer said. “What you have to make sure of is that we hold those people accountable. You do that by teaching in schools what happened and showing them if you allow a person to legislate with hate, we’re in trouble. Democracy is at risk.”

For educators, the event posed different problems; how do they teach current events to students?

“Part of the difficulty is that our students are being exposed to hard things at a much younger age than ever before because of social media, because of their 24 hour news cycle,” Tucker said. “It’s our job as educators, not to prevent that from happening, but to come alongside them and help them see either both sides of an issue or to understand it and process it on their own.”

The 2020-21 school year is further defined by COVID-19. The ongoing pandemic hit the United States in March limiting schools’ capability to deliver instruction. For Brandenburg, this meant shifting most of the interactive elements of her classroom to a virtual platform.

“I wish there were more ways we could actually bring the history into the classroom or bring the kiddos out into the history areas,” Brandenburg said. “We’ve actually definitely had to get a bit more creative. We love to go on field trips and we can’t. So we’ve had to bring Google Expedition [virtual and augmented reality tour app] and virtual field trips to school. However, it’s something we’ve learned a lot from, and it will change how we teach history. ”

Similar experiences can be found on the secondary level. For de Waal, many interactive experiences that helped students understand APUSH have been scrapped.

“In the time before COVID, our first major learning experience would have been a court trial, which, of course, was the kids’ most favorite thing we ever did,” de Waal said. “It’s very much experience based. COVID-19 definitely affected the fun things we can do, but my kids in U.S. history, if you would ask them if they thought it was fun, [they would say] it was.”

Despite these challenges, Coppell seeks to provide a rigorous history education for its learners.

“Coppell really sees the importance of having a strong social studies program, K-12,” McCoy said. “We want our learners to understand the world they live in, so they can make informed decisions about issues affecting them, especially when they grow older.”

History is an ever-changing field that teaches more than dates and figures.

“What history should teach you are the skills to assess information,” Brock said. “To manage large blocks of information, to recognize those places where the information is complete or incomplete. If you learn those things, from there, the key is just read. [History is] perusing the information in a way where you’re constantly scrutinizing, ‘Where’s this coming from, who is putting this together, what research did they gather, what basis do they have to present this?’”

For schools nationwide, the debate on what to teach in U.S. history classes is never-ending.

“If you’re teaching [a historical event] in sixth grade, it’s going to look very different than how you teach it in 11th grade,” Tucker said. “First and foremost is understanding where the students are at and what they can handle, because at the heart of social studies is teaching our students how to be human, how to coexist with the world around them – and it’s a hard line to walk.”

Follow Akhila (@akhila_gunturu) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.

Akhila is a senior and the Executive News Editor for The Sidekick. She is part of the IB Diploma Programme at CHS and when she isn't doing schoolwork,...

Samantha Freeman is a senior and the executive design editor of The Sidekick. She is on the Coppell High School varsity tennis team and has been playing...