Filling the empty throne of women’s professional tennis

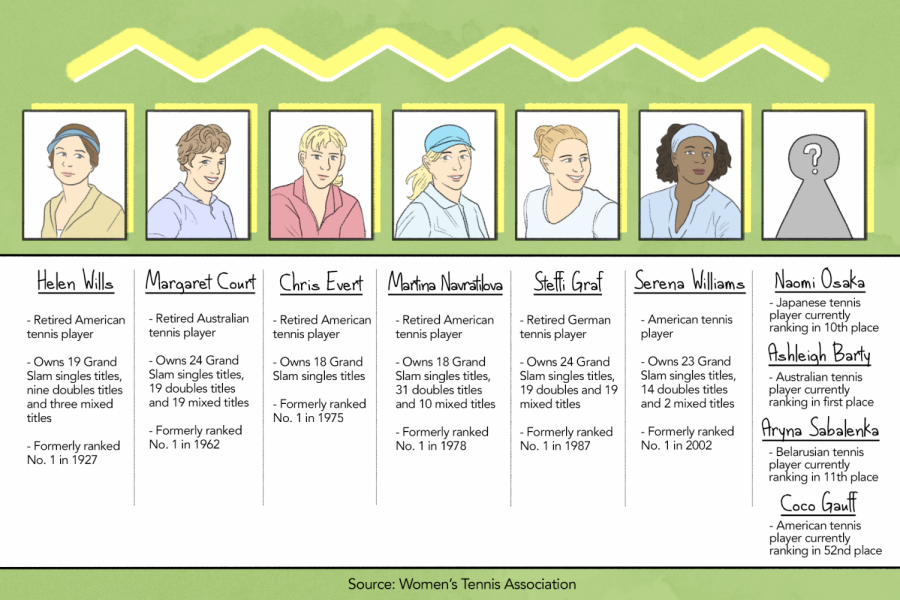

Throughout the years, women’s tennis has always had a gold standard player; Helen Willis, Margaret Court, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Steffi Graf and Serena Williams are prime examples. Sidekick staff writer Anjali Krishna analyzes the current state of women’s professional tennis.

April 2, 2020

After her stunning victory against Petra Kvitova in the finals of last year’s Australian Open championships, Naomi Osaka took the No. 1 world ranking and high regard of the international tennis community. She became the first woman to win consecutive Grand Slam singles titles since Serena Williams in 2015, the other being the U.S. Open late 2018.

Osaka was considered to be the heir the throne previously held by Serena Williams, whose return after childbirth seemed at first to be a smashing reinstatement of the crown, but eventually became shrouded in doubt as she seemed to fade into the group of women who won Grand Slams one day, then lost unceremoniously in the first round of the next Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) 250.

In this year’s Australian Open, Osaka joined that pack, losing to lowly-ranked but promising 15 year old Coco Gauff in the third round. From the moment Williams stepped off the court to now, women’s tennis has lacked a gold-standard player.

While the women’s field is sprinkled with talented players, the group of 20-somethings headlining the sport struggle to break away from the pack and stand out for a specific disruptive style of play. Most women cling to the baseline and serve well within the typical speed range (of 85 to 90 mph), with very few one-handed backhands making an appearance.

Of course, ther are a few outliers to the pattern, such as Aryna Sabalenka’s dominating power and Osaka’s service speeds reaching 125 mph, but no one is as utterly commanding of the game as Serena Williams was for nearly 20 years.

Lacking adventurous, explosive play, the game has come to a near standstill. The competition has all come equipped with solid groundstrokes and baseline play, but no extraordinary point-finishing shots that make a supreme winner.

The stars who were presumed to be the next big names such as Madison Keys, Bianca Andreescu and Karolina Pliskova are all dogged by the same inconsistency as Osaka. 2017 U.S. Open champion Sloane Stephens, for instance, failed to win a single match in the remainder of that season. Nowadays, any match is just about anyone’s as ranking continually decreases in importance and the No. 1 spot seems to be everchanging.

The skills of each player seems to fluctuate by day to day, illustrated by Jelena Ostapenko or Garbine Muguruza, who so flawlessly took out top seeded players to become Grand Slam champions, then fell in the early rounds of the following Grand Slams. More and more unheard of players become title holders and Grand Slam champions, taking their spot in the sun for a tournament or two, then immediately falling from grace.

In contrast, the men’s side of play is dominated by three familiar names: Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, just as the women’s side had been by Margaret Court, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graff before Williams took over. The rivalries between these women were legendary, each of them marking the end of an era of rule.

The issue with the lack of pacesetters in women’s tennis lies in that the group of headliners becomes larger every day, failing to create recognizable names and rivalries keeping the game alive. The group blurs into an unmemorable assembly line of faces, and the threat of the loss of fans and future players inspired by these pacesetters looms.

The threat does not seem to be imminent at Coppell High School, as the number of girls entering the tennis program have slightly increased, though there are still fewer girls than boys, according to Coppell tennis coach Rich Foster.

Considering this trend at the professional level may lead to a discovery of why the current professionals are left in a cycle of sameness. The smaller number of girls at the high school level may lower the competition it takes to make it to the next level of skill.

“The uncertainty I see on the girls side has less to do with their rank than with their dreams and aspirations,” Foster said. “The boys tend to hold on to their tennis hopes/dreams (college play, scholarships, state playoffs etc.) longer than the girls.”

The lack of competition may hinder the development of a killer shot or adventurous style of play and allow girls to stick to the basics, as we see in the WTA. The boys’ side, on the other hand, is drenched in ambition.

“I’m not really sure why that is, but I have boys who might be ranked in the mid 20’s on our team ladder who still cling to their hopes and desires to make varsity,” Foster said. “I have far more girls who choose to move on to another interest when they are not ranked among the top players.”

If utilized correctly, several of the pack have the specialty to become the next big name. The aging Angelique Kerber could return to the top by crafting her game around her unique left-handed play, Sofia Kenin could continue her run as 2019 Most Improved Player of the Year, increasing her wide variety to net play and Ashleigh Barty could find firepower to match her vision of using all parts of the court. Others such as Muguruza, Johanna Konta, Simona Halep, Gauff and Elina Svitolina can do the same.

A champion emerging with a game-changing element? A growing group of talented individuals that fluctuate in the ability to win from day to day? One thing is for sure: women’s tennis needs a gold standard for the sake of both professional and school-level aspirations.

Follow @anjalikrishna_ and @SidekickSports on Twitter.