The clock strikes 8:40 a.m. Lines of Coppell High School students stream down the sidewalk as they complete their walk to school. Bikes are fastened to the racks near buses unloading hundreds of students. The parking lot buzzes with teenage drivers and experienced parents alike.

By the time the clock flashes 8:50 a.m., CHS is filled with thousands of students who all found their way to class differently. The school has entered a new era of transportation, marked by less student drivers and increased usage of alternate transportation.

Disappearance of drivers

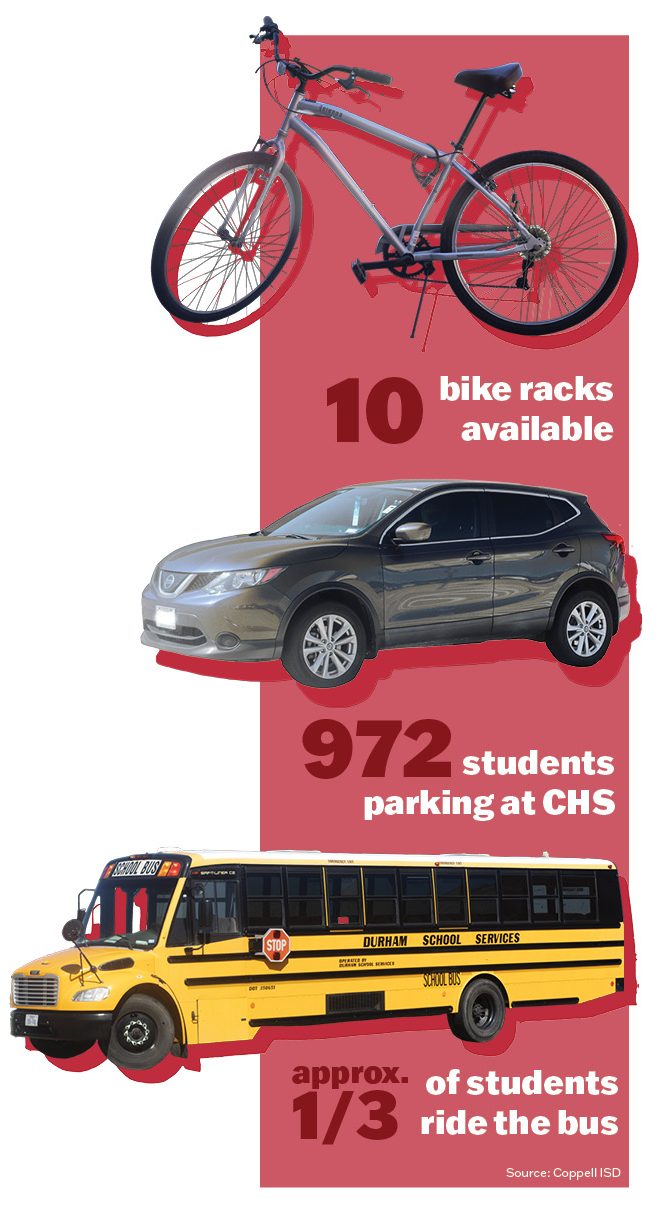

Senior Jackson Cusano’s eyes landed on a sea of parking stickers when he first visited Coppell High School in 2014. When he parks in the same lot today, despite the school being home to almost 3,000 students, he finds half of the spots empty.

Cars no longer seem to be the favored choice of transportation at CHS. The current student body, dissuaded by the congestion in the student parking lot and neighboring roads during dismissal times, is increasingly choosing to ditch the car keys and find other substitutes.

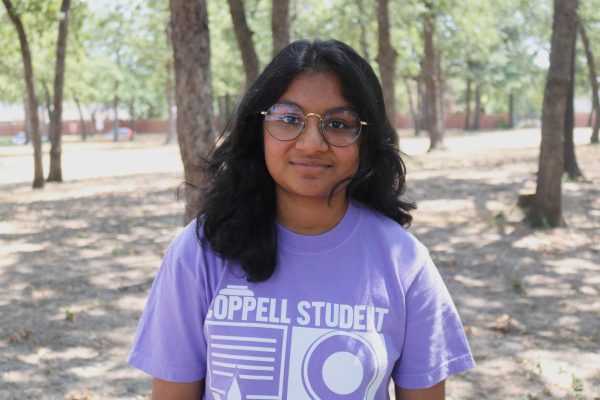

“For me, walking to school is faster than driving to school because the traffic is unpredictable,” junior Nishka Vartikar said. “I don’t want to wake up at 7 in the morning to get to school. I took an afternoon release period so I can relax and go home, not to get stuck in the parking lot for 15 minutes.”

The increased indifference to driving of today’s students marks a large difference from the driving culture prevalent in previous generations.

“When I was growing up, we couldn’t wait to get our driver’s license to get out of the house and as far from the parents as possible,” assistant principal Colleen Lowry said. “But, we could only connect with our friends in person, so that was a motivating factor to get a driver’s license and have some freedom. Because current students can connect to each other online and through social media, there’s not that motivation.”

As fewer students step behind the wheel, many are inhibited in their ability to participate in co-curriculars dependent on community interaction, such as the student broadcast program KCBY-TV, the student newspaper program The Sidekick and the education and training career cluster, all of which consist of students leaving campus to pursue educational assignments.

“When students don’t drive, it limits their ability to experience certain schools,” education and training facilitator Raneta Ansley said. “It can be crippling to the program growing when you have fewer and fewer drivers.”

With fewer people driving to school, education and training students have adapted to alternative transportation methods by biking and walking to schools nearby and even training in CHS special education classes.

Yet, the decrease in car drivers is causing concern in adults for the development and experiences of current teenagers as they leave high school and step out into different communities. Having a car provides invaluable experiences to students.

“It teaches you responsibility and communication skills,” Cusano said. “I am responsible for my car and if I get in a car accident, then I am fully responsible for my actions. And genuinely, I just love my truck so much. It’s the community of having a bunch of people in your car and listening to music with each other; it brings warm, fuzzy feelings.”

Students swarming to buses

A bell rings at 4:15 p.m., signaling the end of the school day. For the next 45 minutes, Lowry listens attentively to her walkie-talkie, sitting on her red chair in the Small Commons. She inputs the numbers of the latest buses pulling in while overlooking the rambunctious congregation of hundreds of students to her right.

Getting a car was once a rite of passage for every 16-year-old and driving was a necessary part of teenage life. Today, 26 buses are the preferred choice of a thousand students for transportation according to Lowry, representing one-third of the student body.

“It’s a convenience thing,” Lowry said. “The parents don’t have to come and pick them up or leave work to come get them. You have a ride to school and home, so you do not have to worry about parking, driving and all of that.”

Like a self-fulfilling prophecy, the increased dependence on buses reduces CHS traffic. Despite car congestion persisting due to the sheer numbers at the school, the consolidation of students into buses largely clears parking space and nearby roads.

“If all of the bus drivers were driving cars or if their parents were picking them up, the parking lot would be even more congested than it already is,” Lowry said. “We are grateful to have the buses to be able to take out a third of our learners home every day.”

Yet, the convenience buses provide comes with a price. Relying on unpredictable outside transportation, students must compromise on their in-school activities.

“I have to miss out on club meetings and such just to catch the bus,” junior Anushka Joshi said. “If I wasn’t as reliant on the bus, I probably would join more extracurriculars because I would have more time.”

The shift in students favoring buses over cars has overwhelmed the current capabilities of the transportation system. It is not uncommon for buses to be continuously late or filled to the brim with high schoolers.

“At the beginning of the year, a lot of us had to sit three to a seat,” Joshi said. “All of us still didn’t fit on the bus, so kids had to sit

on the floor. The first day of school I came by car at around 9:50 a.m. because my bus didn’t come until after first period.”

Additionally, the Durham School Services bus system has faced issues with construction occurring on major roads such as Belt Line Road, resulting in irregular detour routes and inconsistent arrival times.

“Students at times are waiting for 20-25 minutes at the bus stop for the bus to come,” Parkside West neighborhood parent Rajiv Singh said. “That’s valuable time that students are losing, just waiting for the bus.”

Durham and Coppell ISD are working to alleviate the many issues bus riders face, focusing on improving routes. The district works with municipalities of Coppell, Irving, Dallas and Cypress Waters to be notified of road closures ahead of time to reroute buses efficiently.

“With information from surrounding municipalities and us having a great partnership with them, we’re able to make some good decisions as we have obstacles or opportunities come up,” CISD chief operations officer Chris Trotter said.

Additionally, Durham plans to attend the upcoming district job fair to hire additional drivers to supplement its current staff. The district also seeks long-term improvement to the bus system, purchasing 14 new buses through the 2023 bond package set to start service in the upcoming school year.

“New buses will be available for the next school year to where if we needed to add more routes, we don’t have the constraints of not having enough buses,” Trotter said. “That provides an opportunity to have better transportation operations each and every day.”

An expansion into Irving

Joshi settles into her bus seat as she gets on in the morning, ready for a 30-minute ride to school from Parkside East, an Irving community settled at the edge of Coppell’s zoning district.

As the area’s population has increased, the school district has grown further into Irving to support this growth. These regions quickly garnered settlement as families tried to send their children to CISD schools.

To accommodate recent builds including Lee and Canyon Ranch Elementary Schools, the district expanded its zoning further into Irving and Las Colinas to serve more people, including communities such as Parkside, Bridges, South Haven and Cypress Waters.

Hundreds of families have moved to Irving communities to send their children to CISD schools. However, issues occur as these students advance to the high school level. Every morning, they need transport to the other end of the district to get to class.

The 2019 rezoning of Parkside residents, all situated past State Highway 114, from Lee to Canyon Ranch has isolated students from their closest elementary school, Lee. Now, these families face even longer commute times to get to their schools.

“It has been difficult, and not only to get to high school, but elementary school as well, especially after the rezoning happened,” Singh said. “It takes about 15 minutes to get to either CHS or Canyon Ranch for any reason.”

As parents are forced to send their kids to distant schools, difficulties arise in transporting students.

“Honestly, it would be a lot easier for me and my parents if I lived closer,” Joshi said. “I know a lot of people walk home from school, but for me, when my dad picks me up, it takes an hour of his time.”

Students residing miles from CHS face extensively long times for bus-drop offs. On days when the buses face delays, driver absences or alternate routing, the commute lasts even longer.

“I’ve seen a lot of times that they merge the routes and the buses are actually in communities which are much closer to the school, which are also at times very off the route,” Singh said. “So, at times like these, they reach home at 5:35-5:45 p.m.”

The commute for parents and students from Irving communities is too long to justify the amount of time and gas money spent. Instead, many families are left relying on the bus system for transportation to school efficiently, even with its setbacks. In the event of after-school activities, some parents choose to carpool with others in their area, although carpooling quickly becomes difficult to coordinate with the separate zoning of neighboring Parkside communities.

“In Parkside itself, it’s a little bit difficult because Parkside East and West are about 5-10 minutes apart,” Singh said. “It’s still better because you don’t have to drive every time so it saves you a trip, but on the day you drive, it adds about 8-10 minutes. But again, the challenge is that you need to find someone who is in the same club that has signed up for the same time.”

Follow @CHSCampusNews on X.