Waging an inevitable war (Part 3)

Media literacy in youth, strategies to increase objectivity

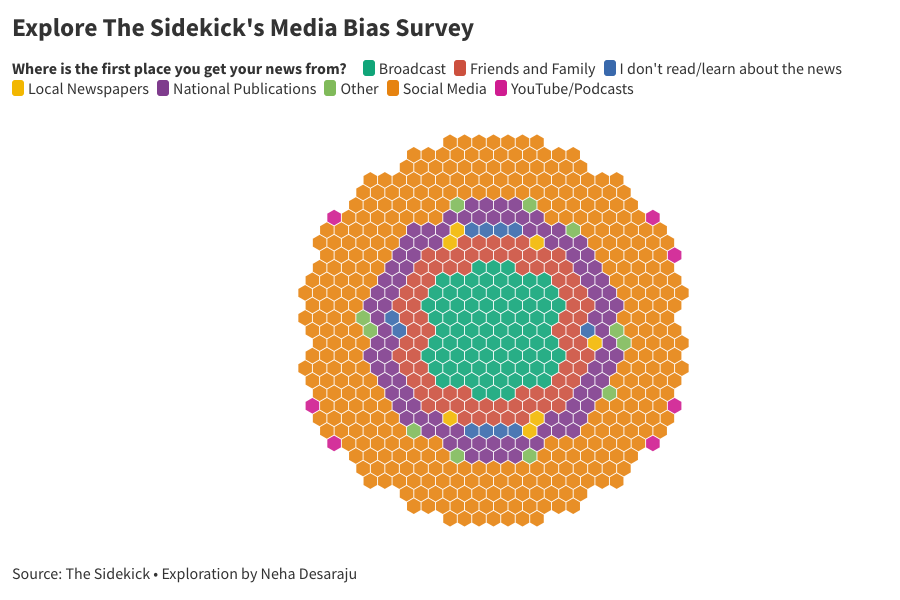

A survey of 659 students at Coppell High School found that more than half first received their news from social media. A lack of media literacy in youth has revealed the importance of student journalism. Graphic by Neha Desaraju

February 26, 2021

Editor’s note: This is part 3 in a series exploring today’s news media and the impact of distrust on its consumers. Read part 1 and part 2 here.

Youth and the media

As the torch bearers of digital news, changes in consumption and accessibility have led today’s youth to face a new, more dangerous battlefield.

In a survey conducted to understand what news sources high schoolers interact with, 659 Coppell High School students were asked to identify their first source for news, how often they checked the news, what sources they typically engage with and how biased they thought these sources were.

The results revealed that the majority of students, 54.6%, first received their news from social media, followed by national newspaper publications (14.3%), broadcast media (13.1%) and friends and family (12.4%). Students most commonly checked the news weekly (39.2%), with 34.4% checking the news daily and 8.6% never engaging with the news.

Of the 17 news sources listed, Fox News and CNN were perceived to be the most biased, followed by Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Furthermore, most students (54%) believed the news source they interact most with to be “a little biased,” and 41.6% believed it to be “moderately biased.”

“When I first find out things, it’s usually from social media, but I usually look at another platform too, because a lot of platforms are biased,” CHS senior Anokhi Patel said. “I definitely have my own views for a lot of things, and I do get information that confirms what I believe, but to gain an understanding of events, I always try to seek someone else’s perspective that is different from mine. A lot of people are choosing to be ignorant.”

Given the prevalence and accessibility of social media, many students get their news from infographics and posts made by other individuals, with content being tailored to align with their beliefs through internet and social media algorithms.

To AP psychology teacher Kristia Leyendecker, the environment students grow up in – the third most common source of news in the survey – also plays a large role in determining what news sources they engage with and the ideologies they are exposed to.

“Our environment is the number one factor that determines what we’re willing to hear, look for and believe,” Leyendecker said. “How we handle that is individual. It’s not uncommon to find that most kids reflect the beliefs of their parents. It’s what they know.”

Children who are exposed to specific beliefs or party affiliations at an early age are more likely to adopt the ideologies of their parents.

“Particularly in youth, it’s really difficult to go up against somebody who believes something differently than you and have the confidence to stand up for what you think when it goes against your family or faith institution,” Leyendecker said.

To Coppell High School Principal Laura Springer, the dangers of not being exposed to new ideas and perspectives is exacerbated by utilizing social media as a main source of news, as it is often unverified and subject to misinformation.

“My major concern is that [today’s] generation of kids believe everything they see on Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat as real news,” Springer said. “I don’t know if there’s a vast majority that get on different types of news stations and hear real news. You cannot use social media as a truthgate, and if you do, you’re going to end up in a lot of trouble in life.”

Studies have also shown that if children were brought up in more authoritarian households they tend to be more conservative when compared to being raised in egalitarian households. Some studies have shown that as children grow, they tend to become more liberal as well.

“Kids go off to college and are introduced to different ideas and different ways of thinking, and that may change or counter what their parents believe or thought,” Leyendecker said. “Higher education has always been considered liberal, but higher education really teaches people to question and look at information like an onion. You’ve got to peel away the outer layers and keep peeling down until you get to the facts.”

Media literacy, the ability to think critically about media sources and evaluate their legitimacy, is not a skill that is required to be taught in most U.S. states. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many budget cuts have removed journalism majors and programs, in which students are often taught such skills.

“You’re learning communication skills that are transferable to anything else,” KCBY-TV adviser Irma Kennedy said. “We reflect on what’s going on in our world, and we’re able to put it in perspective by offering opinion, interviewing people and hearing from them to enrich our own perspective. As a reporter, you’re not only expanding the connections that you make, but you’re helping other students see things through a different lense and gain empathy.”

To Kennedy, the benefits of journalism programs extend beyond helping students pursue a career in the field; rather, it teaches them greater media literacy and gives them the ability to be more informed citizens.

“Anyone can be a citizen journalist, but the thread of ethics involved in making decisions that are offering a balanced, fair approach is what we teach in these classes,” Kennedy said. “If you don’t have that, you won’t have the same perspective.”

The search for objectivity

With less than 10% of students believing the news source they interact with is “not biased at all,” bias seems to be pervasive through the media. Thus, it can be difficult to form objective opinions that consider various perspectives.

To founder of The Trust Project Sally Lehrman, part of the solution relies upon diversifying your news diet and reviewing trust indicators such as journalistic expertise, labeled purpose and diverse sources.

“It’s good to rely on more than one news source,” Lehrman said. “Pick your favorite news source and maybe that’ll be the one that you follow, but consider what it might be missing. Say you follow your local newspaper, but you should also be looking at national news sites and consider what voices you don’t hear.”

Narayanan, who intends on pursuing a career in international relations, relies on multiple sources and checks think tanks (institutes dedicated to research based analysis) to interpret current events.

“The place I go to first is always Reuters and Associated Press, because they’re wire news services, so they report just the facts and there’s very little analysis,” Narayanan said. “If I am going for analysis, I occasionally check out NPR. More often, I try to go to think tanks, because people have written research papers on them, so they’re backing analysis up with evidence.”

In Walsh’s experience working at Trusting News, local journalism sources retain more trust within the community, as local journalists are often more accessible to receive feedback and can be held more accountable for their content.

“We see that our local newsrooms seem to have more trust when it comes to covering local issues,” Walsh said. “We encourage journalists to show them that you’re a part of the community because they will be more likely to trust you because you’re a person in the community.”

To The Dallas Morning News vertical news editor Beth Frerking, a majority of journalists are consistently trying to be objective and fair in their reporting.

“The people that are on the ground doing the reporting, they’re just getting the best story they can get,” Frerking said. “They are not getting paid to give their opinions, because that’s not what they’re supposed to do. They’re supposed to tell the story with all elements involved, and the way to do that is to be assiduously careful, thorough and represent all sides. The reporters I knew did that.”

Combating Distrust

“I was really struck by the fact that when news media all went digital, news media started to have more clickbait headlines and ethics were thrown aside a bit,” Lehrman said. “Everybody blamed it on the digital environment, and I thought, ‘Why can’t we flip the picture? Why can’t we use the digital environment to support quality journalism?’”

With the surge of information accessible through digital news, combating distrust could be getting more difficult. However, organizations such as The Trust Project, which focuses on ensuring quality content abides by eight trust indicators (best practices, journalist expertise, type of work, citations and references, methods, locally sourced, diverse voices, actionable feedback), and other fact-checking websites are playing a large role in restoring trust in quality journalism.

While many platforms prioritize educating the public and increasing their trust, Trusting News focuses on creating change through journalists themselves.

“The goal of Trusting News is really to show that journalists have to be a part of the solution,” Walsh said. “We primarily work with journalists to rebuild trust by focusing on being transparent and engaging with their communities. By engaging with the community, we can involve them in our process to make stories more reflective of the communities we serve.”

This type of community engagement is more easily found in local journalism sources, due to increased accessibility to reporters and the opportunity to break stories first.

“We try to keep in touch with the community and go to the community to ask what we’re doing right and what we’re doing wrong,” Frerking said. “We’re trying to increase trust in communities that have traditionally been underrepresented in the news. We have trainings constantly on good reporting practices. People call us. People email us. People write us letters. We really try hard to get back to people when they have questions and concerns about our coverage.”

Frerking thinks many are unaware of the efforts most journalists put in to create fair, balanced reporting.

“People that don’t know what [journalists] do, they don’t know how devoted they are to their profession and doing it correctly,” Frerking said. “That’s the part that hurts the worst. That people assume we sit around and say, ‘How skewed can my reporting be?’ It’s quite the opposite. It’s ‘how thorough and full and complete and representative can my reporting be and how can I push myself to do even better?’”

Without trust in the press, misinformation and disinformation can unfairly sway citizens’ views.

“If people don’t trust their news information and they go to other bases where information isn’t as vetted, they might trust information that is incorrect,” Walsh said. “Good information is power, and if people can trust news organizations that are providing ethical, reliable content, then they have reliable, accurate information that impacts everything we do. It’s really dangerous for trust to be this low because it creates a chaos of information and people don’t know where to go.”

In the future, news sources are only expected to increase. However, with the onslaught of information comes a responsibility to differentiate between quality content and misinformation.

If distrust in the press continues to rise, threats to democracy can continue to deepen. In order to heal the wounds, both journalists and the public need to adhere to higher ethical standards and if not, risk creating new battles in the inevitable war.

Follow Avani @AvaniKashyap03 and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.