A few cards short of a full deck

Athletic programs’ missing key components in sexual assault policies

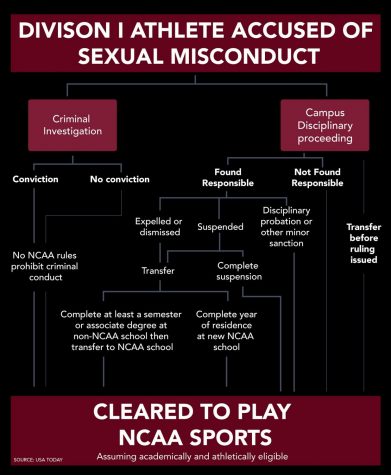

According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, one out of every five women gets assaulted at some point in their lives. The Sidekick staff writer Yash Ravula brings attention to high school and college athletic sexual assault and how they often go dismissed. Graphic by Shriya Vanparia.

March 23, 2020

**Disclaimer: the following article includes discussions about sexual assault, which may be sensitive to some readers**

With the rise in movements such as #MeToo in 2017, many women have come forward talking about their experiences with sexual harassment and abuse. Since, numerous popular sports figures such as Felipe Vazquez, ex-Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher, Luke Walton, a former NBA player and current coach of the Sacramento Kings, and Larry Nassar, a former USA Gymnastics doctor, have been accused of sexual misconduct.

Many of these accusations have been against people in the entertainment and sports industries, which have been happening for decades.

The offenders are more likely to choose victims who have been previously assaulted and in hindsight, a victim who reports multiple complaints is less likely to be believed. The number of false allegations is overestimated in the media, which has led to many cases where the offender is let go without any charges, according to a paper written by the research directors at “End Violence Against Women International”.

While I was doing research on sexual abuse, about half of the cases I read about were about athletes who “made a bad choice” in regards to sexual misconduct, where the case is often dismissed by the athletic program either at a college or high school level.

“Anytime districts put together athletes, they want to be represented well. There is nothing worse than a district that can’t garner support from the community because of scandals. No one wants this bad reputation for their athletic program,” Coppell girls basketball and softball assistant Andrew Martinez said. “So yes, there is a level of protection that happens for any district, and unfortunately in some cases, this means protection of the athletes.”

Look at the case of Jane Doe v. Forest Hill school district, which was decided by the federal court in March 2015 based in Missouri. In November 2010, “Jane Doe” was sexually assaulted by a male classmate. The star basketball player “MM” (because of his status as a minor) committed sexual assault by dragging Doe, a cheerleader and a soccer player, into a soundproof band room and assaulted her, and then attempted to rape her.

Doe confided in her teacher, who notified the principal and the school resource officer, as well as Doe’s parents. Though the parents requested the school to take steps to remove settings where MM can interact with Doe, the school shifted Doe schedule and not MM’s because they “didn’t want to cause him inconvenience.” Along this time, other students blamed Doe for bringing “bad reputation” for their star basketball player, whose suspension would impact the team’s success.

He pleaded guilty to lesser juvenile charges and was given a 1-year suspension from school (after two more victims came forward with accusations). The school district also was sued for $600,000 in 2015 for mishandling the investigation.

This is one of the clear cases where the school did not do its duty as an educational center in order to favor its “star player” because it did not want to ruin his career. In April of 2014, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights released an updated policy interpretation clarifying the legal responsibilities of colleges, universities and public schools to address sexual violence and other forms of sexual discrimination under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. A juvenile can be charged with “indecency with a child” (found in section 21.11).

“[At Coppell High] school, there are a set of regulations we have to follow, there are many moving parts. Even before we step in the investigation, we have got the authorities to do a full investigation, and we have to get the parents involved in this as well. All these codes come into play,” Coppell ISD assistant athletic director Dr. Nicole Jund said. “Because these incidents can happen to anyone at any time, it is a part of my job and any coaches here to provide a safe space for athletes, both boys and girls.”

Every sports program at Coppell High School has family groups, where a coach is assigned to a group of student athletes. The coach is responsible for being their person or mentor that athletes can look up to. This is an efficient way for athletes to have a safe, non-judgmental space to talk to someone in a higher power or just someone who is willing to listen to them. This system is critical when someone has been sexually assaulted.

“Whenever we go out of state for tournaments, there have been times one of my student athletes asked me to walk them to their car or whatever, and I’ll be glad to walk with them. As a coach, it’s your responsibility to build that trust with your student athletes,” Martinez says.

So what makes athletic programs’ want to save their student athletes?

A quick Google search suggested that 65 schools of the 2,078 (about 3%) in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) were responsible for $7.8 billion in revenue through athletes in 2018 according to the conversation. That’s how much the athletes bring to the college and the program they are in. Naturally, colleges would prefer to protect their athletes than lose them over a sexual assault case. That paired up with the mentality of “that’s what men do” is a disastrous recipe for these athletes to walk away from crimes.

The NCAA metes out punishments to student athletes for bad grades, smoking marijuana or accepting money and free meals. But nowhere in its 440-page Division I rule book does it cite penalties for sexual, violent or criminal misconduct. Therefore, any student athlete playing Division I sports accused of sexual misconduct can find loopholes in the system to remain on the team, according to USA Today.

This is exactly how victims sometimes do not feel safe in the place they are supposed to feel safe at. These examples are just one of the millions of cases – one in five women get sexually assaulted every day. And the perpetrator is let go, often without any punishment.

These horrible crimes by the schools and colleges can be fought if the victims come forward and talk about the assault that happened to them.

“Victims of sexual abuse need to come out and tell someone. It’s not something they have to keep to themselves,” said CHS senior Katie Odum, a defender on the Cowgirls soccer team.. “By going out and talking to the police or the counselor you are not only helping yourself, but you are also helping the other girls who have been sexually abused come forward and talk about their issues. This will help destigmatize talking about these hard topics, which honestly, whether we like it or not, can happen to anyone and anywhere.”

If you or someone you know have been a victim of sexual assault, please talk to parents, teachers, or school counselor or call:

National Sexual Assault hotline: 1-800-656-4673

National Domestic Violence hotline: 1-800-799-7233

National Suicide Prevention hotline: 1-800-273-8255

National Child Abuse Hotline: 1-800-422-4453

Follow Yash (@yashravula) and @SidekickSports on Twitter.

Shivi Sharma • Mar 23, 2020 at 4:11 pm

This story explores its sensitive topic so well. Good job Yash!