Black History Month: Signing the stories of those unheard, unspeaking

ASL students study Black History Month through lens of the Deaf and black

Coppell High School American Sign Language teacher Erika Trammell teaches signing phone numbers and addresses with her seventh period class on Tuesday. Trammell and the CHS ASL team are teaching classes about Black ASL and influential Deaf African American people in honor of Black History Month.

February 28, 2020

Upon entering an American Sign Language classroom at Coppell High School, your greeting is a warm silence and a simple hand movement, rather than traditional chatter filling the air. To the members of this class, though, the hand movements are as understood as any spoken language is.

In honor of Black History Month, the ASL teachers are shining light upon a group whose history often goes unheard – the black and Deaf community, a group of people enduring both racism and ableism in the past and the modern world.

“This month for me, is an expression of my culture,” CHS ASL teacher Erika Trammell said. “Being an African American teacher, I want to show off my side, my culture, and for the black and Deaf, there’s even more to it. They’re two minority groups, and being both means facing double the prejudice.”

The formation of the black and Deaf community traces back to segregation times, when those Deaf and black were prohibited from joining organizations such as the NAACP and the National Association of the Deaf.

The rejection from both Deaf and African American communities forced this minority to create their own groups that would dually combat ableism and racism. In Washington, D.C. in 1981, a local committee organized Eastern Regional Black Deaf Conference at Howard University, from which emerged the National Black Deaf Advocates.

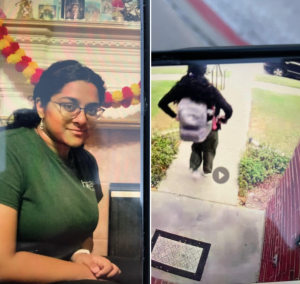

“I think it was really interesting to understand how black history relates to Deaf history,” Coppell sophomore Anna Vazhappily said. “They’re both minority groups we were able to learn about how they each evolved in society to be viewed as they are today.”

Today, the community focuses on raising awareness of the issues they are facing and defining their culture as one syncretic of both African American and Deaf. One of these differences aligned specifically with the ASL classes – the difference in sign between black and mainstream ASL.

“A long time ago, schools were segregated, but also, schools for the Deaf were segregated,” Trammell said. “So you had white students only around white students and black students only around black students, and there was a dialect formed there off of English, and it was the same for forming a different kind of Black ASL. It became a dialect. If I was signing with a white person, I would say, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to do that,’ but if I was signing with someone who is black, I would go, ‘Oh, my bad.’ The meaning is equal, but the way we sign it can be a little different.”

As when teaching any LOTE, part of teaching ASL is learning about the culture the language is from. According to CHS ASL teacher Delosha Payne, within the Deaf community, being Deaf is not considered to be a disability, but rather a culture, not an impairment to be fixed. Those Deaf do not consider themselves hearing impaired, because it implies that something is wrong with them.

“People tend to think that the Deaf are disabled,” Payne said. “And Deaf African Americans have a double negative, because they face racism and ableism. It’s important to recognize what they are doing this month to let people know that the Deaf and African American can do anything and everything.”

Follow Anjali (@anjalikrishna_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.