By Daphne Chen

Editor-in-Chief

Every student and teacher knows the telltale signs. A yawn and a stretch. The ever-so-slight glance of eyes to the left and right. The glint of an iPhone held casually beneath the table, away from the prying eyes of teachers.

It’s cheating.

And to some, it’s also a survival technique. In the words of one sophomore student, “If you care about it enough, you cheat.”

The Pressure

In 2003, a survey conducted by UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute found while the percent of high school students who maintained an A average in 1968 was 17.6 percent, that number had inflated to 46.6 percent in 2003. Essentially, students who make straight As in high school today are simply… average.

Biology teacher Jennifer Martin hears these kinds of statements from grade-obsessed students all the time. Martin teaches allegedly one of the toughest courses in the school, AP Biology, attracting ambitious students who want to beef up their courseload. Martin says she sees cheating happening in the upper 25 percent of students – not the lower quartile.

“I’m very concerned about our focus on grades because I really feel like it is leading to the degradation of integrity in our students,” Martin said. “I really wish Coppell would not give class ranks until your senior year. I think that would help at least a little bit.”

Eighty-one percent of public high schools use class rank. As more and more nearby school districts are eliminating class rank on student transcripts, such as Carroll Independent School District (its new policy will start with the Class of 2011) and Highland Park, both highly competitive school districts. CISD is also considering the change.

“We are exploring it and letting Southlake and Highland Park take the lead on this,” Dean of Instruction Gina Peddy said.

In school districts this competitive, the pressure to be “number one” can reach extreme levels. Just 20 minutes to the east and six years ago at Plano West Senior High School, valedictorian Jennifer Wu and salutatorian Sarah Bird had GPAs that differed by .00154 points. Bird sued the school board to be named co-valedictorian, demanding that her unweighted As for playing on the basketball team (treated as a P.E. course) be taken off of her transcript. She won.

A 1999 Who’s Who survey published by The Heartland Institute found that 95 percent of high-achieving students who had cheated in the past reported never being caught. However, the CHS administration wants students to know that those are caught will not get off easy.

“If the teacher reports [cheating] to the administration, the administration acts aggressively on it,” Peddy said. “It could eventually become a Compass placement. We do not want our students to cheat. They represent CHS for the rest of their lives – good, bad or ugly.”

Private school differences

Private schools often deal with cheating a bit differently than large public schools. Many have honor councils to hear the students’ “case” and make a decision like a jury.

At the Episcopal School of Dallas, all students are required to sign the honor code and promise not to “lie, steal or cheat”. If a teacher accuses them of breaking the code, their case is brought before the honor council, an organization consisting of three elected student members from each grade and the Student Council president. Both the student and the teacher present their side of the story, and the honor council members make a judgment on the student’s guilt and set a punishment, which usually includes a one-day suspension and a letter of apology to the teacher and dean.

“The thing about private schools is that it’s all about community,” ESD Upper School Dean Eddie Eason said, noting he himself is a product of a large public high school. “We have about 400 students, and with our 100 seniors, it’s really family. The way we look at it, an honor violation is an offense against the school community.”

The dealings of honor councils are almost always kept highly secretive; at ESD, talking about any cases of the honor council constitutes a violation of the code in and of itself. The mysteriousness of honor councils makes the idea of cheating all the less tempting for students at these tight-knit schools, a closeness CISD may not have.

“Coppell tends to be a very religiously-based community,” Peddy said. “And yet the students almost OK cheating. It’s interesting how students can rationalize copying and cheating and still go to church every Sunday.”

CHS also experimented with an honor council-esque program about 12 years ago when the school was smaller, called the Academic Integrity Committee. Unfortunately, for a school so big, too many petty complaints were brought in and the idea fizzled.

The Definition of Cheating

One of the difficulties in punishing cheaters is that the act itself can be an ambiguous. The CHS 2009-2010 Student Handbook states: “Students found to have engaged in academic dishonesty will be subject to grade penalties on assignments or tests and disciplinary penalties in accordance with the Student Code of Conduct. Academic dishonesty includes cheating or copying the work of another student, plagiarism, and unauthorized communication between students during an examination.”

But what about more ambiguous scenarios? The Sidekick surveyed over 100 CHS teachers and students about eight possible situations and whether or not they constituted “cheating.”

The scenarios:

1. Skipping a day of school to take a test later 2. Writing acronyms or notes on your hand to look at during a test 3. Asking a student who has already taken the test “what I should know” 4. Reading Sparknotes for its analysis to finish English homework 5. Taking advantage of a teacher who guides students to the answer instead of restating 6. Students working together on take-home worksheets or packets 7. A student is playing on his phone during a test. Do you assume that he was cheating? 8. You see a student glancing around the room during a test and it looks suspicious. Do you assume that he/she was cheating?

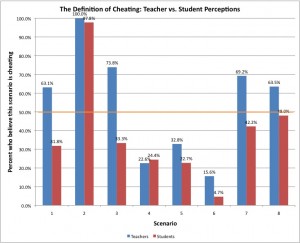

The survey reveals for almost every single scenario on the survey, a greater percentage of teachers versus students believe the given scenario is an act of cheating.

“Asking a student who has already taken the test ‘what I should know,’” the third scenario, illustrated the greatest different between teacher and student opinions: Nearly 74 percent of teachers believed that this was a form of cheating, compared to only 33 percent of students.

“Sometimes, teachers tell you to study whatever and then the test ends up being way different,” senior Matt Speer said. “It’s like they’re trying to trick you. So that’s when I ‘cheat’ the most. Whenever the test is different from what they tell me to study, I don’t feel regret at all because that’s not fair to me as a student.”

But what ignited the most debate between teachers and students was the fourth scenario: “Reading Sparknotes for its analyses to finish English homework.” Although teachers and students found themselves in basically agreement as far as how many believed using Sparknotes was cheating – 23 percent for teachers and 24 percent for students – many found the question too subjective and commented that using Sparknotes in lieu of reading was cheating, but allowable as supplementary material.

Others didn’t find the question so subjective, like an anonymous teacher who simply circled “Yes” in response to the survey question “Is this cheating?” and wrote, “The worst of all. =)”.

However, most students don’t seem to think so.

“It’s way too crazy for me to try to read the whole book and not understand a word of it,” senior Aagya Sharma said. “If you just read the summary, then you can get the whole thing. You’re actually just utilizing your time.”

As the percentage of students who admit to cheating rises each year along with the pressure, a highly competitive environment may be affecting the way teens think about their education negatively rather than positively.

“People feel like it’s worse to get a bad grade than get the punishment,” senior Marco Arce said.

However, Peddy does not believe that the high-pressure academics should be an excuse.

“Because of the need to get the GPA up, to take the advanced classes, I think people justify it because ‘everybody does it’,” Peddy said. “I understand the pressure. Life’s all about pressure. But I think it’s a cop-out, to be honest.”

Eason sees ESD’s approach to cheating differently.

“There is no shame in not being able to do some schoolwork, but a lot in turning in something that is not yours,” Eason said. “We are constantly reminding kids that honor is everything.”

Interestingly enough, sophomore Connor Wilcox said something that parallels Eason’s words.

“People will do anything to get into college, into the top 10 percent,” Wilcox said.

“Rank is everything.”

So what will CHS students choose to sacrifice?