House of Sharing visits Coppell, spreads awareness of comfort women

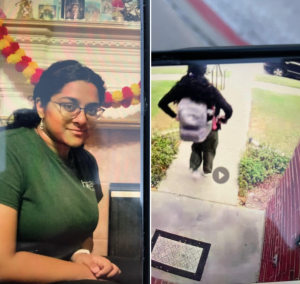

War survivor Lee Ok-Seon holds hands and talks personally with CHS junior Duyoung Cho. “She thanked me for being here, and said that usually, they can’t tell if there are any Korean people in the crowd, so she said it was nice of me to come up and talk to her,” Cho said.

April 22, 2016

The pain of the past can be changed by the strength of the present.

On Thursday in the Lecture Hall, Coppell High School students had the unique opportunity to meet Korean war survivor Lee Ok-Seon.

Lee, along with members with the House of Sharing, spoke to students of the tragic events that happened to her as a “comfort woman” during World War II.

The term “comfort women” refers to the thousands of young girls who were victims of sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army during the war. For years now, there has been an increasing demand from the Korean public for an official apology and proper compensation from the Japanese government for the acts that were committed. Both sides have continued to go back and forth on reaching a suitable agreement.

Lee, along with members from the House of Sharing, talked to students and answered questions about the issue.

“I’m sorry for taking your time,” Lee said. “But what else can I do? I was taken to the [comfort stations] and beared the knife, I was beaten and I was covered in bruises and have still survived from that point on. I want to spread this issue to the young people.”

At age 15, Lee was abducted by soldiers in 1942 and taken to a “comfort station” in Yanji, which is now the Jilin province in China. At the stations, women “serviced” up to 40 soldiers a day, and were severely assaulted.

“I thought of committing suicide, but I realized that I had to survive, I had to live to get payback for all the crimes and atrocities and terrible experiences that I gained,” Lee said. “I felt like I needed to get justice.”

At the moment, there are 44 known survivors remaining. With the women growing older, there has been a stronger push to get justice for the victims in time.

“I just felt like there are too many people [in Dallas] who do not know about this issue,” translator and advocate Sinmin Pak said. “So I just wanted to bring awareness and touch people’s hearts and then motivate them and have them wanting to do something.”

Pak is hopeful of the future and what it could potentially do to bring these tragic events to light. As a mother of three former CHS students, Pak was the one who proposed to host the event to International Baccalaureate (IB) history teacher Michael Brock.

“I feel really fortunate that we had this opportunity to have someone actually associated with the events that we just discuss in class that makes it that much of a more present experience and it makes it easier to connect to our own lives,” Brock said. “It’s really living history.”

The students, as well, felt this issue resonate within themselves.

“I thought it was really great to hear them talk, especially by bringing awareness and bringing support to the women who went through such suffering and atrocities,” CHS junior Joanne Jung said. “It’s good to know how we can support them.”

Lee, along with her fellow survivors, hope to continue the movement until it reaches their final goal of receiving justice.

“They worked for so long but they still haven’t received that official apology that they’re really thinking,” Pak said. “So maybe it’s Dallas that is the place that can actually do something that turns the tide.”

Mallorie Munoz • Apr 27, 2016 at 10:02 am

Awesome story, Amy! Good job.

Racn Kel • Apr 23, 2016 at 9:38 pm

“Comfort women” is a suitable theme to study journalism principle, examine objective primary source and both side assertion on your own account.

see “Points in the dispute at a glance, ‘comfort women’ ” – https://sites.google.com/site/olnatidy/astboacn

Hope you’ll be a good writer. Thank you.

Meha Srivastav • Apr 23, 2016 at 11:11 am

It’s so cool that our students got to meet her and experience this!