By Sakshi Venkatraman

News Editor

@oompapa1

As freshmen transition to sophomores and as sophomores transition to juniors, success-driven students increasingly begin to stand apart from the majority.

There are many facets that make up a modern day high school “success”. These include a high grade point average (and a subsequently high class rank), a good Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) score and participation in clubs and extracurriculars. The pressure to balance these scholastic aspects along with friends, family and personal life leaves many students overwhelmed and begging the question: what sacrifices do I have to make to be an academic success story?

“The types and amounts of pressure [on students] have definitely increased,” Coppell High School Principal Mike Jasso said. “There tends to be a culture of competitiveness [at CHS] and that can be healthy. But when taken to an extreme, what happens sometimes to some of the kids here at the high school, is that they don’t lead a balanced lifestyle. They lose perspective on the importance of academics; there is also a need for social and emotional well being.”

Jasso said the pressures students experience today are much higher than the pressures on students “even five or 10 years ago”. In recent years, being an “A” student has become not just common, but it has become the norm amongst highly achieving students.

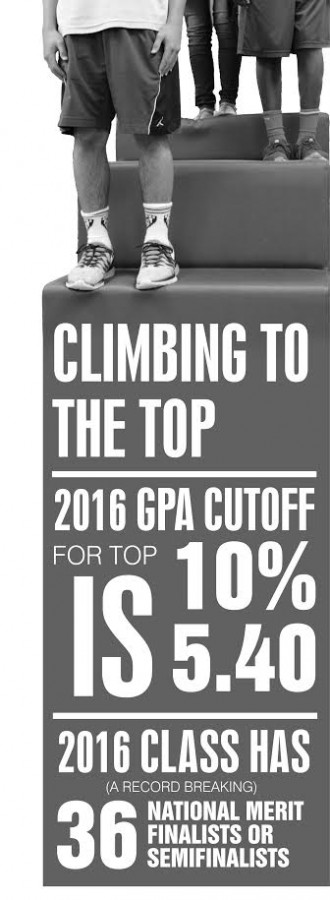

The GPA cutoff for that class of 2016’s top 10 percent remains at 5.40, according to Naviance Career and College Readiness Platform. There have also been record breaking numbers of students achieving the title of National Merit Finalist or Semifinalist, with 36 this year alone.

“We do have kids [at CHS] who choose to challenge themselves for very genuine and very good reasons by taking large numbers of Advanced Placement classes,” Jasso said. “Pressure, in and of itself, can be a positive thing when it is handled well. But when it becomes overwhelming for a student, it may lead to things like academic dishonesty.”

Although working hard certainly bears fruits, students who aspire to graduate in the top of their class claim to be feeling the pressures of “making it big” academically.

“There is a lot of stress with homework,” top five percent junior Meghna Suresh said. “I feel like teachers are not even giving us any time between the all-nighters we pull. It’s like, you go to school, you go home, you start your homework right away and you are still pulling an all-nighter. If teachers give us lessons to do at home, and a project to do on top of that, how are we supposed to finish it all? Imagine that times seven. That’s our workload.”

Jasso encourages teachers to be mindful of this workload and guide students on their journey for a valuable, meaningful education.

“[Teachers should] be mindful of the amount of work, whether that’s homework or in class work that [they assign],” Jasso said. “As a principal I would say, let’s assign work that is meaningful and necessary versus busy work. That would be a responsibility that [teachers] hold in order to not make that situation worse.”

Suresh describes her struggle to keep the balance between her core class work and her extracurricular activities, which include choir and Health Occupations Students of America (HOSA).

“Choir is very intense,” Suresh said. “You have to perform your level best even if you have a test the next period. Extracurriculars totally put us to a standard; even though they should be relieving our stress, they are still adding to it.”

Suresh notes that another addition to the weight on students’ shoulders is the grade-centric environment of high school, specifically CHS.

“There are cliques at our school based solely on ranks,” Suresh said. “You are popular, among your group, if you have a high enough rank. You are looked at as almost godly; everyone respects you. If you [don’t], people treat you like crap.”

Although most of this affinity for higher ranking students seems to be centered around the students, Suresh says that teachers contribute to this division as well.

“Some teachers are emphasizing grades more than learning and I feel like it should be the opposite,” Suresh said. “Students should want to come to school to learn the material, not to get a certain grade. ”

From the multifaceted standpoint of grades, Suresh says parents play an extremely important role in the amount of pressure on their children.

“How do you pay back your parents for all they do for you?” Suresh said. “You pay them back by making them happy. How do you make your parents happy? By getting good grades. Their identity is based on their grades.”

Though the outlook of some students may be that reducing academic pressures, homework and course intensity may benefit the student body, teachers of these high intensity courses do not necessarily share that opinion.

Advanced Placement U.S. History (APUSH) teacher Diane de Waal, for example, says that her class, being one of the most material intensive ones at the high school, prepares kids for what they will face in higher education and future jobs.

“I have taught for over 25 years and [high school] is much more intense now, I agree with that,” de Waal said. “The sad part of that is that it leads people to make poor choices such as cheating into grades rather than doing the learning. I really do not know where that pressure comes from but it seems to bring out the worst in people.”

De Waal and her team of AP U.S. History teachers rigorously plans the homework schedule to try and give students periods where they do not have the usually daily reading homework.

“I don’t think I would [make any changes to the College Board material],” de Waal said. “You have to understand the scope of history from beginning to where we are now. The material is pretty condensed, if not too simplified.”

In 2007, de Waal’s daughter, Caitlin, graduated ranked No. 5 from CHS, so the former AP Human Geography teacher has had a firsthand taste of the high expectations from top students. She wants to make sure her students realize how to manage their time and that high school does not last forever.

“If you want to achieve that top recognition, you are going to have to work hard for it,” de Waal said. “It doesn’t go on forever but it does go on for a few years and if that’s what you want you will have to work for it. This a competitive school; it depends on what you want your future to hold.”

De Waal’s daughter, a recent law school graduate, described her higher education like “having five jobs”.

“For those who want to get to the top of society both economically and socially, you are going to have to work to get there,” de Waal said. “That is really the American mantra.”

Regardless of the workload, de Waal says that the collaboration and material learned in high school can translate to the rest of a student’s life, shaping their life in college and in future jobs.

“In [AP U.S. History], for example, it is really about who we are as Americans and the role that we play in the world,” de Waal said. “It is about training your brain to be who you want to be.”

As far as academic pressures are concerned, Jasso advises students to seek support of teachers, parents and counselors in their endeavors to rise to the top.

“Ultimately, [students] have to continue to reevaluate their situation to determine: is this goal still my goal and is it a worthy goal and I am willing to pay the price to reach that goal,” Jasso said. “That gets back to having a support system and involving parents in [academic] decisions.”