Nine years old.

That is how old Philadelphia resident Anthony Samuels was when he saw his first shootout with his own eyes. But Samuels recalls that the violence did not end there.

“When I was 10, I saw my first drug transaction,” said Samuels in an interview with the American Federation for Children. “When I was 11, it was the first time I saw someone get killed. And it wasn’t the last.”

Samuels grew up near Strawberry Mansion High School in Philadelphia, a public high school frequented by violence. For Samuel, the Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit (OPTC) voucher program was an outlet to a different life. He was able to attend Abington Friends School, a private school in Jenkintown, Pa.

“My life would have been completely different if I didn’t go to Abington,” Samuels said in the interview. “And I wouldn’t have been able to continue on at Abington without the scholarship. I’ll be forever grateful for the program. It saved my life.”

School vouchers attempt to offer money to parents directly for a student’s tuition to any school. While public and charter schools are funded by taxpayer dollars, private school vouchers offer alternatives to families looking for private education from private or religious schools. Texas currently doesn’t offer such programs.

For Coppell resident Nagashree Suryanarayan, sending her eldest son, Pranav Sreenivas, to Greenhill School in Addison during his freshman year was a decision based on the extracurriculars he wanted to pursue.

“It had nothing to do with the competency or the caliber of Coppell High School, which we love,” Suryanarayan said. “It was a personal decision. We felt like there would be more flexibility in terms of some of the extracurriculars that we were interested in. For instance, debate, robotics and orchestra were three things that he was keenly inclined on.”

But her youngest son, Prajit Sreenivas, attends Coppell High School Ninth Grade Campus.

“The same concept applies in terms of interest and which one provides better opportunity,” Suryanarayan said. “With my younger one, his big focus has been band. He made varsity in his freshman year for percussion, which is pretty big. There is no comparison between a huge school like Coppell and its band relative to a smaller school where band is definitely not a prominent extracurricular. It felt like he would be better served in a school like Coppell.”

Families within Coppell continue to make the decision between staying at Coppell High School or transitioning to a private school like Suryanarayan, but the debate on voucher programs in Texas may impact that decision.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott has advocated for a school voucher program since January, speaking at a variety of private Christian schools. At a rally at Annapolis Christian Academy on Jan. 31, Abbott expressed his support for school choice and the expansion of Education Savings Accounts (ESAs). Abbott’s extension of the program comes from a similar form of a savings account made to students with disabilities in 2020.

“It’s been so successful,” Abbott said about the program to The Dallas Morning News. “But that program shouldn’t be limited.”

This idea has been reflected in Senate Bill 8, authored by Senator Brandon Creighton. This bill would provide families up to $8,000 to use for private school tuition and other school-related expenses. The bill would use the ESA program to put state funding into accounts that parents can use to pay tuition.

“We have the obligation to give Texas students more choices,” Creighton said on the Senate floor. “It empowers parents to make decisions for better outcomes.”

That bill was approved by the state Senate on April 6 in an 18-13 vote.

While the bill was originally proposed with no limits on income, an amendment passed in April on the Senate floor reserves 10 percent of ESAs for lower-income families. The remaining has no income eligibility requirements.

However, after much discourse, the bill died in May after the House tried to limit the scope of the legislation. The House’s scaled-back version of the bill made eligibility for the proposed voucher program exclusively available to only certain groups of students, such as those with disabilities or those who attend schools that are considered “failing” according to the state’s accountability rating.

House Bill 100, another push to implement vouchers, didn’t fare any better. This bill intended to allocate $4.5 billion in new funding for schools, but the Senate tried to modify the bill to include an education savings account similar to the one in Senate Bill 8. Lawmakers failed to reach a compromise and forced the bill to death.

On Sept. 19, Abbott confirmed that he is to call back for a special session on “school choice” in October. He further declared Sunday, Oct. 15 as “School Choice Sunday” calling for pastors to support school choice legislation. Abbot has even promised political consequences if legislation doesn’t pass before the primaries in March.

“In that first special session, we will have another special special session and we’ll come back again,” Abbott said. “And then if we don’t win that time, I think it’s time to send this to the voters themselves.”

While many share the same story as Samuels, the rejection of House Bill 100 has been cited for many reasons. For one, funding for vouchers comes from the money the state has already allocated for students’ public education. The risk of losing funding has been a worry for many public schools including Coppell High School.

“I hate school vouchers,” Coppell High School Principal Laura Springer said. “When we operate as a public school, we are told by the state what tests to give, enrollment and attendance requirements. All those things are tied into money we get. But when you start taking money from that pot where we already don’t have enough money, you just lessen the amount of things we can do.”

With the already increasing teacher shortage, Springer worries about what a decrease in funding might mean for hiring teachers.

“We won’t be able to offer some classes because I don’t have enough teaching staff to fill those speciality courses,” Springer said. “When it gets to the point where I have to limit what students are all able to have, that’s wrong.”

Even for Suryanarayan, school vouchers take away too much money from public schools to benefit private schools only by little.

“As much as I’m a private school parent and I would appreciate the money, I do not believe in the voucher system,” Suryanarayan said. “At St. Mark’s School of Texas or Greenhill School, you’re looking at upwards of $40,000 in terms of annual fees. $8,000 in comparison because of vouchers, is 20% or less of that funding. When multiple people take that $8,000 away, it has a bigger dent in the public school system. The quality of a public school goes down if you start pulling away resources.”

School revenue is based on attendance, so funding would be lost with every student who decides to attend a school other than CHS.

“It’s a twofold situation: we lose kids, we lose funding,” Coppell ISD Board of Trustees President David Caviness said. “The other side of the equation is that there is only so much money available for public education. So if the state is now diverting local taxpayer money to private companies for private education, then there’s no way they can continue to properly fund public education, and they’re already behind in terms of how much we need per student.”

But vouchers are just a subset of the umbrella of “school choice.” A key component of the choice can be seen more locally through the implementation of charter schools. Charter schools, similar to voucher programs, can take money away from districts based on student attendance.

Coppell ISD consultant Bob Templeton has analyzed trends in public education enrollment and the number of students who transferred out of Coppell to attend other schools including charters such as Great Hearts Texas, Harmony Science Academy, Manara Academy, Texas College Preparatory Academy, Universal Academy and Uplift Education. According to Templeton, transfers have increased from 739 students in 2017 to 928 students in the 2023-24 school year.

The basic allotment per student on average for school districts is around $6,500 per student. The change from losing around 200 students is roughly $1.3 million.

A prominent issue with the implementation of charter schools is the fact that independent school districts lose local control. The charter schools’ application approval process goes through the Texas Education Agency (TEA), which then approves the charters to be located throughout the state. The local school districts, however, are cut out of this equation.

“It becomes a loss of local control when the state controls [charter schools],” Templeton said. “In a sense, the residents of Coppell ISD are paying for charter schools that are located in other areas. Their tax dollars are going to charter school operations that they don’t get to have a say in.”

Public school districts don’t have a choice if a charter school is placed in the boundary of its district. This then impacts ISD’s predetermined five to 10-year plans for primary facilitation.

“In some situations, it means that public schools can be in the wrong location so there are now underutilized buildings,” Templeton said. “The expansion of choice, while on the surface, sounds like a good thing for parents. But what it does is create planning challenges for local school boards, because this is outside of their control and outside of their knowledge. Many times these charter announcements come just weeks or months before the school is going to open so there’s not enough time to redo your plan and change your facility utilization to account for the last-minute decisions.”

Coppell ISD has an advantage of holding a good academic reputation compared to certain charter schools.

“ [When looking at schools for our son], the charter school was a different comparison.” Suryanarayan said. “Charter schools are a strength-in-numbers kind of model, so if you have a large number of students, then you are able to get a lot more funds diverted from the state towards the school, so they will be able to leverage that. That works well at least through elementary school, but as you progress into middle and high schools, you’re looking at a lot of extracurricular activities that need a lot more additional funding for the right coaches and the right instructors.”

Families from underperforming schools, according to Templeton, are more likely to use voucher funds to send their children to better schools.

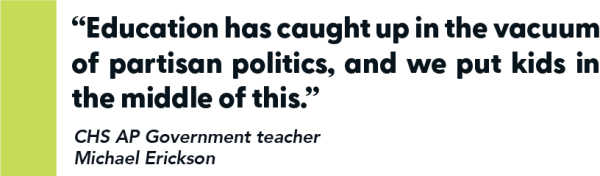

“I like the idea in theory that it gives people a choice with what to do,” CHS AP Government teacher Michael Erickson said. “People say education is funded with our tax money and therefore it’s our money. For kids and parents who are in school districts with issues, dangers or low funding, it allows them to choose a different school than what they’re forced to go to which can be positive.”

The use of school vouchers offers autonomy to choose schools outside of what students are zoned in. By creating options for students to find a safer school or one that matches the needs of a family, students may feel more comfortable. Students desiring special education resources, for example, might find a better environment.

“It’s all political, which is a shame because no matter what side you support, the government is taking education which is one of the most important things in this country and reducing it to a political talking point,” Erikson said. “Education has caught up in the vacuum of partisan politics, and we put kids in the middle of this.”

Follow Sri (@sriachanta_), Anushree (@anushree_night) and @CHSCampusNews on X