One bad apple

Negative side of team loyalty rots original intent

Students are told that telling anything to an adult makes one a “tattletale” or a “snitch,” including when someone committed a wrongdoing. The Sidekick executive editor-in-chief Sally Parampottil writes about the negative side of team loyalty and the resulting hesitancy to tell on friends and teammates when they have committed a crime.

Snitches get stitches.

Don’t narc on me.

Tattletale.

From a young age, the concept of reporting wrongdoing has a stigma attached, a little negative social label stuck onto those who dare speak up. When it comes to sports, the fear of this label is combined with team loyalty ingrained in the program and the desire to win that fuels competition.

Months of practice and training, sharing highs and lows, experiencing wins and losses and making memories at team dinners build family-like bonds within athletics – bonds that can sometimes be too strong.

It is a recipe for a series of hidden disasters.

“In society, a narc is worse than the perpetrator,” Coppell ISD Athletic Director Kit Pehl said. “The narc can be looked upon worse than the person who [is guilty of the bad] behavior. That’s why it’s so important that in the culture you build, you build accountability into where somebody tattling is less likely to be necessary.”

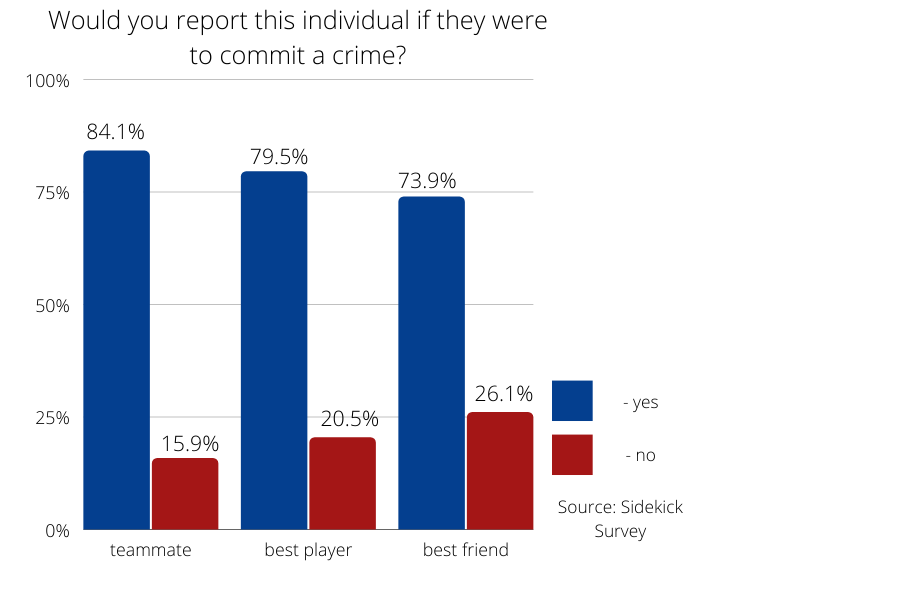

In an anonymous Sidekick survey sent out through Pehl to all head coaches of Coppell High School sports, varsity and JV athletes were asked in three questions whether they would report a teammate, the best player on the team and their best friend if they were to commit a crime such as theft, steroid abuse and sexual assault. Eighty-eight responses were collected, with athletes representing eight sports.

Though the overall majority on each question was “yes” as in they would report the crime, the percentages dropped with each question. For reporting a general teammate, 84.1% said yes; for reporting the best player on the team, 79.5% said yes; for reporting their best friend on the team, 73.9% said yes.

“It’s probably a voluntary response survey,” Coppell pole vault coach and AP statistics teacher Don Kemp said. “Probably the ones who did not answer are the ones who did not want to tell. I know there’s a lot of kids where it’s a tag they get on them as a narc if they tell, even if they should tell. There’s probably a higher percentage that won’t tell on a best friend or the best teammate.”

Even with anonymity, not every athlete completed the survey. Its validity remains questionable, as athletes could have lied, and the difference between the hypothetical and reality is unaccounted for.

“In real life, they wouldn’t turn them in, and in real life, it wouldn’t be as valid,” Coppell girls basketball assistant Julieann Hartsburg said. “I think they say one thing, but if it were to actually happen, they’d be afraid of getting caught for tattling. I don’t think they would do what they say.”

The data collected shows a change in people’s decision based on their relation to the player in question. A general teammate is more likely to be reported than the best player, and an athlete’s best friend is less likely to be reported than the best player. To Coppell football coach Michael DeWitt, this is a point of interest, as he had thought athletes would value competitiveness more in the sport. To Hartsburg, this could be rooted in selfishness.

“The only thing I can think of is jealousy,” Hartsburg said. “I know some teammates may be jealous of ‘oh, she gets more play time than me, so I’m not afraid to turn her in because if she gets turned in, that would be more play time for me.’ That’s very catty, so I’m not sure. It stems from how you raise your team, how you instill the work ethic and value, ethical and moral. It does interest me, because I don’t see how they’re so quick to turn in the best player as opposed to their friend, but that’s the only reason I can think they would do that.”

According to Pehl, the bridge between coaches and players comes from team leaders, who serve as a connection on both sides. Accountability on a team requires the help of self regulation rather than solely resting on the coaches to keep track of every athlete.

“We can’t be everywhere; you’d like to be, but you can’t be, so you have to rely on the team leaders [and] the athletes to tell us what’s going on sometimes,” Kemp said. “We’re not at their houses; we’re not at their parties. We’re here two hours a day, so we worry about that all the time.”

When this does not happen, however, issues arise. Kemp, who used to teach in Georgia, experienced times when athletes tried to cover up misconduct. While those examples were caught, it is not known how much flies under the radar.

“We have used tattling for so long as ‘we’re throwing our friend under the bus’ and ‘I’ve got to have my friends’ back all the time,’” CHS Principal Laura Springer said. “I truly believe in having your friends’ back. I’m all about loyalty. You can ask my assistant principals and everyone else I hire, I’m a loyal person until you cross a line. That line is you’re harming yourself or you’re harming someone else.”

On the collegiate and professional level, there are countless examples of coverup stories trying to protect athletes within a program. Baylor University’s football sexual assault scandal revealed massive sweeping under the rug by members of the staff, including former head coach Art Briles.

“When we get to a point where we allow athletes to believe they’re untouchable, and because they’re such a superstar, you can sexually assault someone and not be punished for it, we have taken the worship and loyalty way too far in our life,” Springer said.

The solution, while not clear or simple, all comes down to maintaining accountability. The “snitches get stitches” mentality is still prevalent, and working to counteract that requires holding people accountable for minor things, rather than solely criminal offenses.

“If you cut a corner in practice, like you went inside that cone, if you’ve got the kind of accountability where a teammate goes, ‘Come on man, you’re better than that, do over again,’ as a coach, I’m not going to be irritated with a candidate that skipped,” Pehl said. “I’m going to give praise to the kid that held him accountable. The guy who skipped was weak in the moment. He’s going to recognize that, and instead of getting jumped on for a poor choice of behavior, he’s going to be more motivated to do the right thing next time.”

Athletes who do wish to report a teammate may speak to any of their coaches or counselors.

“There’s a lot of resources for those kids to have those hard conversations,” DeWitt said. “Hopefully we’ve created an environment where kids feel welcome and comfortable to talk about those things because those could potentially be hard conversations.”

While it may be difficult to report someone with a personal connection or with a major impact on the team, the character of the individual with the choice is tested with that decision.

“We have a conversation with our guys all the time that the wounds of a friend can be trusted,” DeWitt said. “There’s times in your life where you need to have friends who are OK and willing to hold you accountable. Even if you do something wrong and it’s going to cost you, they need to confront you on that.”

Follow Sally (@SParampottil) and @SidekickSports on Twitter.

Sally is a senior and the Executive Editor-in-Chief on The Sidekick. While she's done just about everything possible on staff, she loves writing for sports...

Ava Gillis is a sophomore and a staff designer on The Sidekick. She enjoys reading in her free-time and you can often find her in the kitchen making cookies...