From dozens of labs across the world to local pharmacies

COVID-19 vaccines become available to the public

Three COVID-19 vaccines, Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson, are now available in the United States as the pandemic continues. Eligible Coppell residents can receive vaccines by joining distribution centers’ wait lists.

March 2, 2021

Coronavirus Disease 2019. COVID-19. Both imply this was an outbreak isolated to 2019, but the pandemic continues in 2021, after hundreds of thousands of Americans have perished as a result of COVID-19 and pandemic-related mental illness.

Rushed in by medical research companies to save the day are the new COVID-19 vaccines.

“[Getting the COVID-19 vaccine] was exciting,” Coppell ISD director of health services Joyce Alcorn said. “Because it was just a little bit of hope that we’re on a new road, so it was exciting.”

Authorization of the Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccines came after several months of life in the pandemic. This seems like a long time, but vaccine trials typically take anywhere from 10-15 years. The process was dramatically compressed into nine months for the COVID-19 vaccine, due to international competition and cooperation between scientists.

On Dec. 11, Pfizer-BioNTech became the first company to have a COVID-19 vaccine approved for use in the U.S. One week later, the Moderna vaccine was also approved for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

More recently, Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose COVID-19 vaccine was approved. Prior to its Feb. 27 approval, all available vaccines in the US required two doses, spanning 28-42 days apart. Getting only one dose has caused concerns about speeding up the evolution of new and dangerous variants of COVID-19.

“We got COVID vaccines approved in months,” Coppell High School health science teacher and former paramedic Gary Beyer said. “That’s typically what has always happened in Europe, Australia and in other countries, but we’ve always been way more cautious about approving medications than other countries. You can go to Canada and Mexico and get medications that either we don’t have yet, or that are very expensive in this country and pay pennies on the dollar for the same medications.”

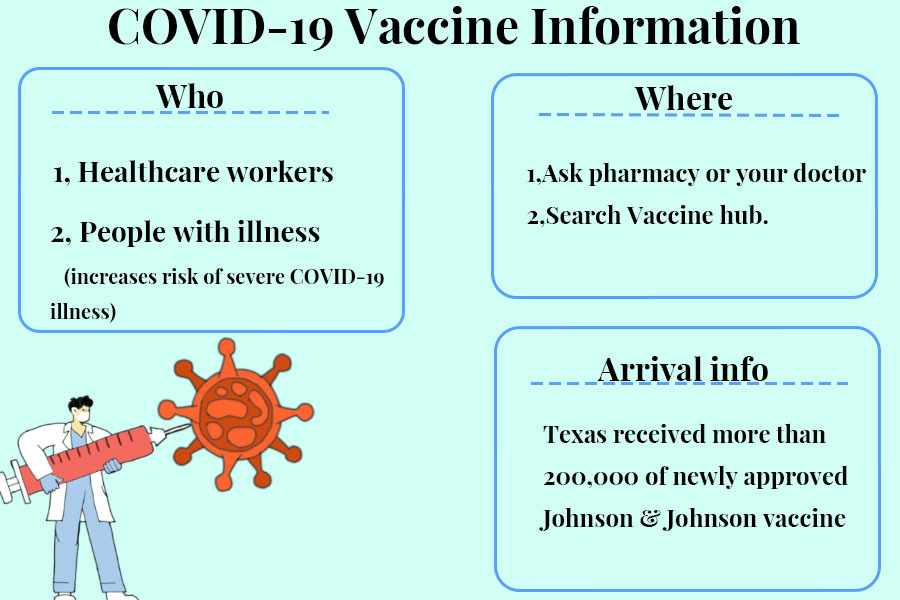

Frontline healthcare professionals were the top priority for vaccination. After that, availability varied on a state-to-state basis. In Texas, there are two phases of eligibility: 1A, covering healthcare workers and residents of care facilities, and 1B, referring to people age 65+ or 16+ who are at a high risk for contracting COVID-19.

In addition to age restrictions, there are other potential barriers to getting vaccinated. One major concern in the medical community is equitable distribution. As racial inequality was thrust into the political spotlight during the June Black Lives Matter protests, medical professionals hope to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines reach communities of color by establishing outreach roles in hospitals and apps about vaccine education all over the country.

Another concern is cost. Medications are notoriously more expensive in America than in other countries. However, the public should not be worried about potential cost barriers to receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. Insurance is guaranteed to cover the cost of the vaccine, and in the case that a recipient does not have insurance, they can apply for government coverage.

When the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were approved, pharmacies were receiving so many calls from the frenzied public that phone call menus began including information about vaccine availability at certain locations. The Market Street pharmacy on Denton Tap Road in Coppell answered an estimated 50-100 calls every day about the vaccine, according to Coppell pharmacist Kent Hertel, The Sidekick student life editor Victoria Hertel’s father.

Market Street pharmacy received its first COVID-19 vaccine delivery on Jan. 5. Overnight, all 100 spots had filled up.

“When we got the first shipment, we thought we would get 100 doses every Tuesday,” Hertel said. “But there is no set schedule. We expect more doses soon, but it could be weeks or even months before we get any.”

While the Market Street pharmacy received 100 doses at a time, county vaccine centers received thousands at once. These go to mega vaccine centers, such as the Dallas County vaccine center in Fair Park.

According to the Operation Warp Speed (OWS) distribution plans, there is no explicit timeline for vaccine distribution. However, the report does acknowledge the possibility that the COVID-19 vaccination might join the list of yearly vaccinations alongside the annual flu shot. This is recognized as Phase Three of the OWS plan, with Phases One and Two involving vaccination of healthcare workers and the broader public.

It should be remembered, though, that control of OWS has changed hands. After the Jan. 20 inauguration, President Joe Biden took control of the federal COVID-19 distribution process. According to a Reuters report, there was very little foundation for distribution left behind by the Trump administration. In the absence of an existing plan, the Biden-Harris administration spent its first day in COVID-19 briefings. Biden’s goal is for 100 million vaccines to be administered in his first 100 days. In the 38 days since his inauguration, more than 70 million Americans have been vaccinated. In spite of the promising rate of vaccinations, though, vaccines have never been pushed out as urgently as the COVID-19 vaccines, and there are bound to be issues.

“[The vaccine distribution process] has been extremely disorganized,” Hertel said. “We expected doses to arrive faster when Biden took office, but they haven’t so far.”

The rollout in Texas was affected by the winter storms and power outages occurring through the week of Feb. 15. As roads were buried in snow and ice, vaccine distribution trucks were delayed, causing appointments for second doses to be rescheduled at the Market Street pharmacy. Additionally, centers with an excess of vaccines requested that anyone who had planned to get the vaccine and was within safe distance of a center to go in and get vaccinated, fearing the expiration of the extra doses.

As vaccination goes back up in Texas, questions arise about how this will affect school reopenings. While CISD has been open for in-person learning for about six months, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has published new guidelines for schools that are beginning to reopen.

“I certainly have my fingers crossed and hope that [more people will be in-person next school year],” Alcorn said. “We’ll be on our way there, but we’ll know more about that down the road.”

The vaccine may take much longer to affect schools, though, because current age restrictions exclude anyone younger than 18, or 16 with pre-existing conditions, to get the vaccine. As more testing occurs, this may change, but currently, most CISD students are not eligible for vaccination.

“If they meet their goal of giving everybody the opportunity to be vaccinated by July, and I think all of that will have a tremendous impact, but there’s still so much to wait and see,” Alcorn said.

However, not everyone is as excited about getting the vaccine. Working against the efforts to create herd immunity to COVID-19, is the anti-vaccine or “anti-vax” movement, which has grown in popularity. Herd immunity occurs when enough people are vaccinated or immune to a disease so contraction in that population is highly unlikely.

“I did research on why anti vaxxers are scared, and [my class] wrote a whole essay about the pros and cons of vaccination,” CHS junior in the health science endorsement Ananya Balaji said. “One of the things I learned was that you have [a very low chance] of dying as a result of vaccination.”

There is some concern as to how the growing movement will affect herd immunity to COVID-19. If more people refuse to get vaccinated, the chances of achieving herd immunity in the United States could be impacted.

“We can’t really control [how the ‘anti-vax’ movement will affect herd immunity] unless the government takes a left hand turn and says, ‘By God, everybody will have [to get] a vaccine,’” Beyer said. “There’s no way to do that, this country is not built like that.”

Follow Anjali (@viola_swan) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.