Unseen, but deeply felt

Living as a teenager with an obscure illness

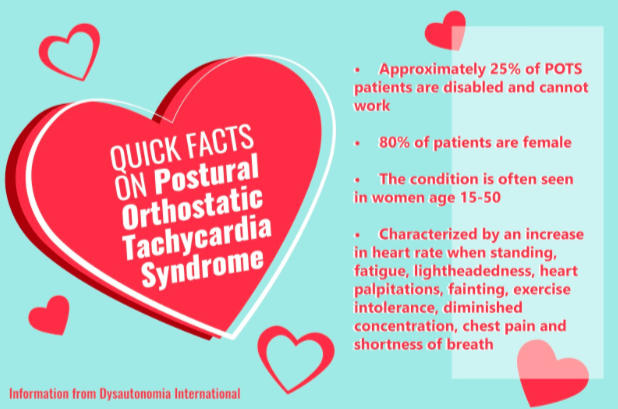

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a blood circulation disorder commonly treated by cardiologists and neurologists. Staff writer Emma Meehan shares her story of being diagnosed with this condition.

October 10, 2019

My heart pounded as my vision blurred, knees shaking as my body weakened and blood rushed to my feet.

I remember thinking I had a concussion, but not being able to explain the actions of my heart or blood.

I was used to my daily run presenting me with some difficulty, but I had never experienced such struggles when exercising. It was seemingly random. The night before, I could run for miles, but that night was different.

I was different. Weaker.

Medical testing, uncertainty and misdiagnosis of my new physical limitations weighed heavy for seven months from that night in October 2017. A concussion was ruled out before I was diagnosed with chronic migraine syndrome, which was later proven incorrect.

I was told to visit a neurologist, then a headache specialist, opthamologist, neuro-opthamologist and finally, cardiologist.

My eventual diagnosis with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) the following May gave me hope and new information about treating my symptoms and improving my standard of life. However, there is no known cure for POTS. I became one of the one to three million Americans affected by the condition every year.

POTS is a blood circulation disorder characterized by an abnormal increase in heart rate when standing. Common POTS symptoms include fatigue, headaches, lightheadedness, heart palpitations, fainting, exercise intolerance, diminished concentration, chest pain and shortness of breath.

With my new symptoms, I couldn’t play lacrosse or take dance classes anymore. Simple tasks such as going to the grocery store and shopping at the mall quickly became strenuous. Even standing in a line could cause blood to pool in my feet. Brain fog made concentrating in class harder and my fatigue made staying up late to do homework or write a story even more draining.

POTS affects every patient differently. Though many can live normal lives and even play sports, 25% are disabled and cannot work. Mobile and able to go to school, I would call myself lucky.

Dealing with my symptoms meant everything in my life became a little bit harder, but not impossible. I can’t run for miles anymore, but I can do moderate exercise. It may be hard to deal with excessive fatigue as a student in rigorous classes, but I have learned to manage my course load.

For months after diagnosis, I only told family and close friends about my condition, trying to conceal it, fearing abnormality. I said lacrosse just wasn’t fun for me anymore and that’s why I quit. I said I didn’t want to take dance classes anymore because it was boring and took up too much time. In reality, I wanted nothing more than to be able to put in my mouth guard or slip on jazz shoes.

Recently, I have felt more comfortable being myself and talking about the serious issues I confront in my daily life. I’m not afraid to confide in friends about the struggles I encounter on a daily basis, and I no longer fear being different.

Whether students deal with a physical struggle or hardship in their personal or family life, they can often try to conceal or hide it from the world to protect themselves, but there are no hopes of improvement or progress in silence.

Follow Emma (@emmameehan_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.