Exploring international classroom dynamics

Finland model proves to be best option for the United States

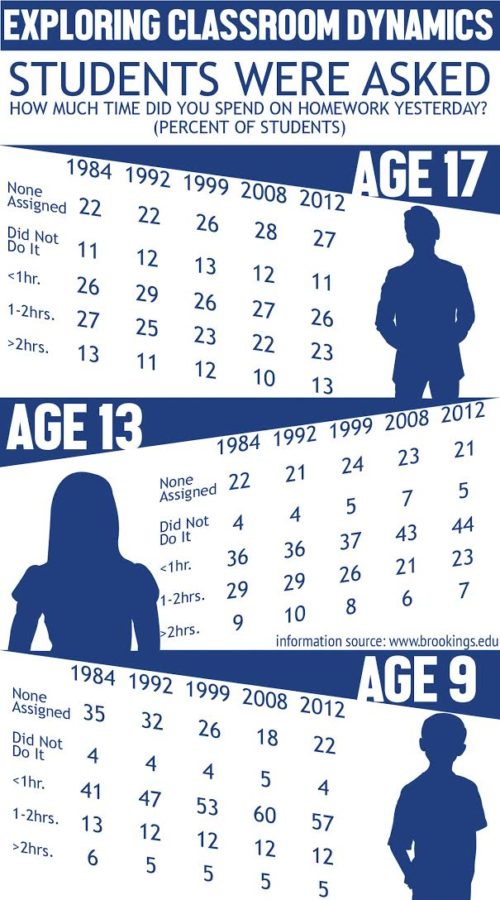

Statistical information on average times spent doing homework for students in the United States.

Coppell High School hosts students that work alongside strong competition and high stakes. In order to manage their workload, many students focus more on the necessary things to get them to the college of their choice, which leaves little room for legitimate education when students are only concerned about improving their GPA.

“I think Coppell has a large percentage of our students which are highly motivated…but I do believe and I do see that we have a percentage of our population also that has a motivation problem,” says lead assistant principal Sean Bagley. “I truly believe that when our teachers reach out to students who might be in one of those situations that I mentioned earlier, that students now have someone they can talk to, someone they can trust in.”

“America’s education advantage, unrivaled in the years after World War II, is eroding quickly as a greater proportion of students in more and more countries graduate from high school and college and score higher on achievement tests than students in the United States,” said Andreas Schleicher, senior education official at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris, which helps countries coordinate future policies.

“The problem is that while there are benefits to staying in school, most students do not benefit very much from working hard while in school,” Cornell University professor John Bishop wrote in his article “The Motivation Problem in American High Schools”.

Fueled with stress, little sleep and disappointment in our country’s education, I found that education reform is currently happening on a spectrum, with countries such as South Korea and Japan on one end of having perfect students, and countries such as Finland and Sweden on the other end, also equally-perfect students.

North America falls somewhat in the middle. Our kids are not reaching the standards that we have set forth with the former NCLB bill and the Race to the Top plan, but we are not doing completely terrible in comparison to third world countries – and isn’t that all that matters?

According to David Lynch, writer for USA Today and ABC News, South Korea has a completely different mindset to students dropping out which sets them apart from our own understanding of the term “high school dropout”.

“[In South Korea], 93 percent of all students graduate from high school on time. But in the United States, almost one-quarter of all students — more than 1.2 million individuals each year — fail to graduate,” Lynch said in his article.

South Korea’s graduation standard is among the highest of 36 other countries examined in Lynch’s study, with the United States being the 18th. What I find most interesting is that in the 1960s, South Korea had an economy and education standard equivalent to many underdeveloped countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. However in the present, they’ve put education at the epicenter of their agenda which has allowed them to boost their economy.

Unfortunately this yields to some pretty hefty standards that weigh down many students.

“The…formula combines fierce societal pressure, determined parents and students who study nearly round-the-clock,” Lynch wrote. “After a typical eight-hour school day, most students spend their remaining waking hours in private tutoring or reviewing schoolwork.”

In a 2012 Stanford Report, writer Stephen Tung argued that what North America sees as students being lazy, Finland sees as vessels of improvement for the future. Finnish students aren’t educated to make money like in the United States. They’re educated to be brighter individuals, hence the relaxation of standards, which also aids in mental stability.

“Finnish students have ranked at or near the top of the Program for International Student Assessment ever since testing started in 2000,” Tung said. “In the most recent assessment in 2009, they ranked sixth in math, second in science and third in reading. By comparison, U.S. students ranked 30th, 23rd and 17th, respectively, of the 65 tested countries/economies.”

“Inspiration for many of Finland’s changes came from research in the United States, which contributes 80 percent of the world’s education research,” Tung reports.

Dr. Pasi Salhberg, a leader in education reform, notes that while U.S. schools moved towards standardized testing and nationalizing their graduate requirements, Finland has taken a more micro-management approach; that is: avoiding standardization of practically any facet of education and allowing schools to address the problem areas of their students with more freedom, thus promoting faster development.

So what is the problem with U.S. schools? How do we solve the fact that we’re not even stagnating but declining in almost every measurable area of education? Do we accept the approach of South Korea, putting education at the top of the list and pushing social and financial pressure on students? Or do we follow Finland’s approach to lack of high-stakes testing and nationalization of practically every facet of schooling (good job North America)?

Are either of these even plausible in a country like the United States?

To promote the mental health and creativity of our students, we should adopt a model similar to Finland. Although South Korea does provide an interesting solution, the United States has not placed education as a top priority to the advancement of its economy. Stress and lack of motivation for students would not yield positive results. Thus the adoption of Finland’s policy as a progressive alternative would be better for the country.

Grant Spicer is a Senior and second year staff writer for The Sidekick. Grant specializes in writing opinions articles and answering those difficult questions.

Austin Banzon is a senior and the Graphics Editor for The Sidekick newspaper. He creates infographics / designs pages using his skills with Photoshop,...