By Henriikka Niemi

Staff Writer

When attending an information session for the University of Southern California at the Marriott in Dallas this past Sunday, I found myself questioning all the classes I had taken throughout my high school career.

We all wonder why we are forced to learn about the anatomy of a frog or how to graph a polynomial function rather than how to write a check, manage loans, or how to file taxes; things that we will actually use after graduation.

Even more than that, why are we forced to take classes we are not interested in? If I become a psychologist in the future, why should I learn about derivatives or World War I?

The USC representative mentioned that the admissions office looks not at how many AP classes an applicant takes, but whether they challenged themselves in the areas of study they were planning to pursue. Yet, they also heavily consider GPA, which most schools calculate as weighted, and class rank. Both of these rely on difficulty of classes.

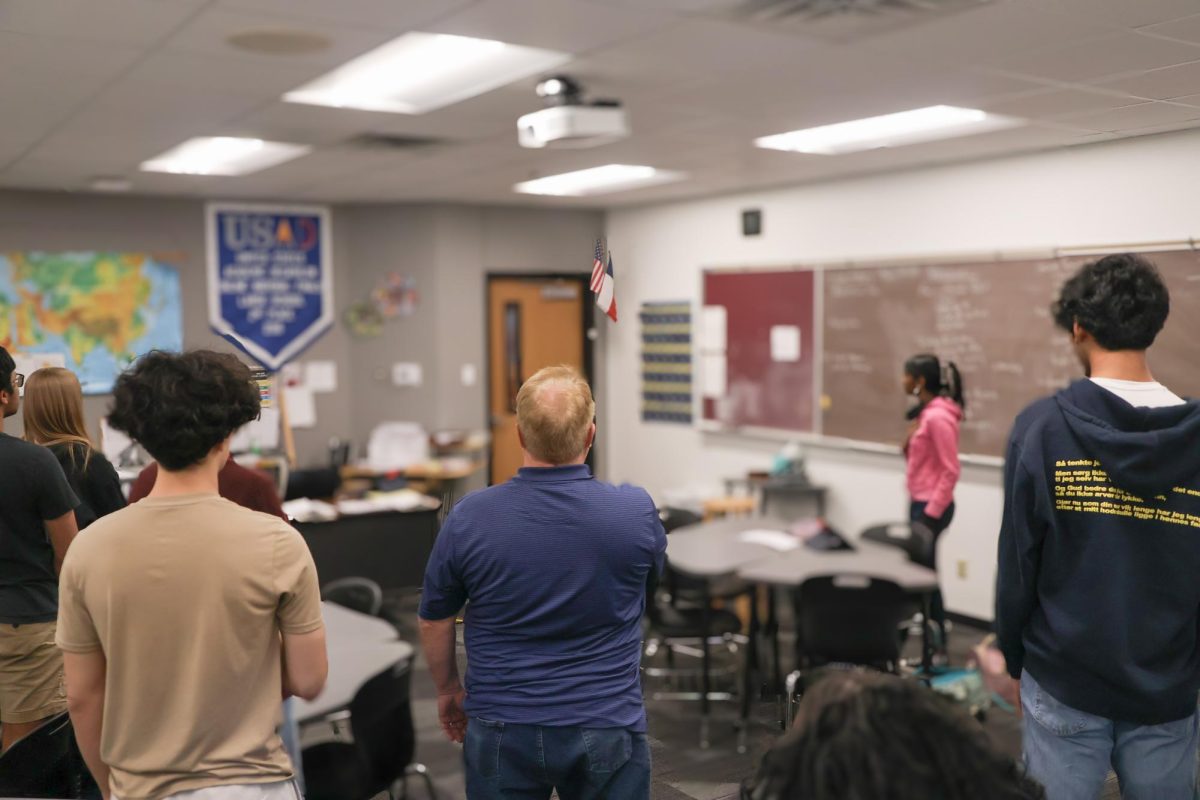

At Coppell High School, there is a trend of filling your schedule with as many AP or IB classes to boost your GPA. I am also guilty of this. This year, four out of five of my classes are AP. I know my strengths, but I chose to challenge myself with as many advanced classes as possible.

Some people are discouraged from taking interior design, forensic science, sociology or photography simply because they are regular level classes. It is not that students do not value their passion, but we all do it for the sake of getting into the college we want. The competitive nature of GPA and rank creates the stressful atmosphere that we are all so familiar with, where we find ourselves constantly refreshing portal and worrying about grades rather than making sure we are learning the material.

Sure, everyone needs to have a well-rounded education to learn fundamentals, since almost every career involves proficiency in writing and math. Advanced math specifically can teach problem solving skills that can be applied to a number of different careers. In addition, well educated people are also more likely to participate in community affairs and politics, which benefits our democratic society.

However, this does not mean that everyone needs to spend a year learning the ins and outs of every subject. If someone wants to be a nuclear physicist, they should concentrate on classes that pertain to that career, such as math and science.

High school should be more about finding careers that we are passionate about. No one wants to be undecided their first or second year in college, especially since tuition is extremely high.

As studies have shown, most people change their career seven times in their lifespan. If we would spend the majority of our teenage years picking classes based on our curiosity or interest, we would spend less time being indecisive in the future.

While it would definitely be difficult to change the structure of our schools, the benefits may outweigh the costs. We should keep core classes, but perhaps design a system that allows a student and their parent to decide which core subjects they want to spend more time on.

It would be impossible to eliminate competition, but if schools nationwide set a limit for the number of AP or IB classes a student could take each year, it would give everyone an equal opportunity to boost their GPA while giving more room in students’ schedules to take other classes that are offered.

School and college applications are arguably the biggest source of stress for teens. This atmosphere could be changed if high school was based around classes that interest students and finding a potential career.