By Kristen Shepard

Staff Writer

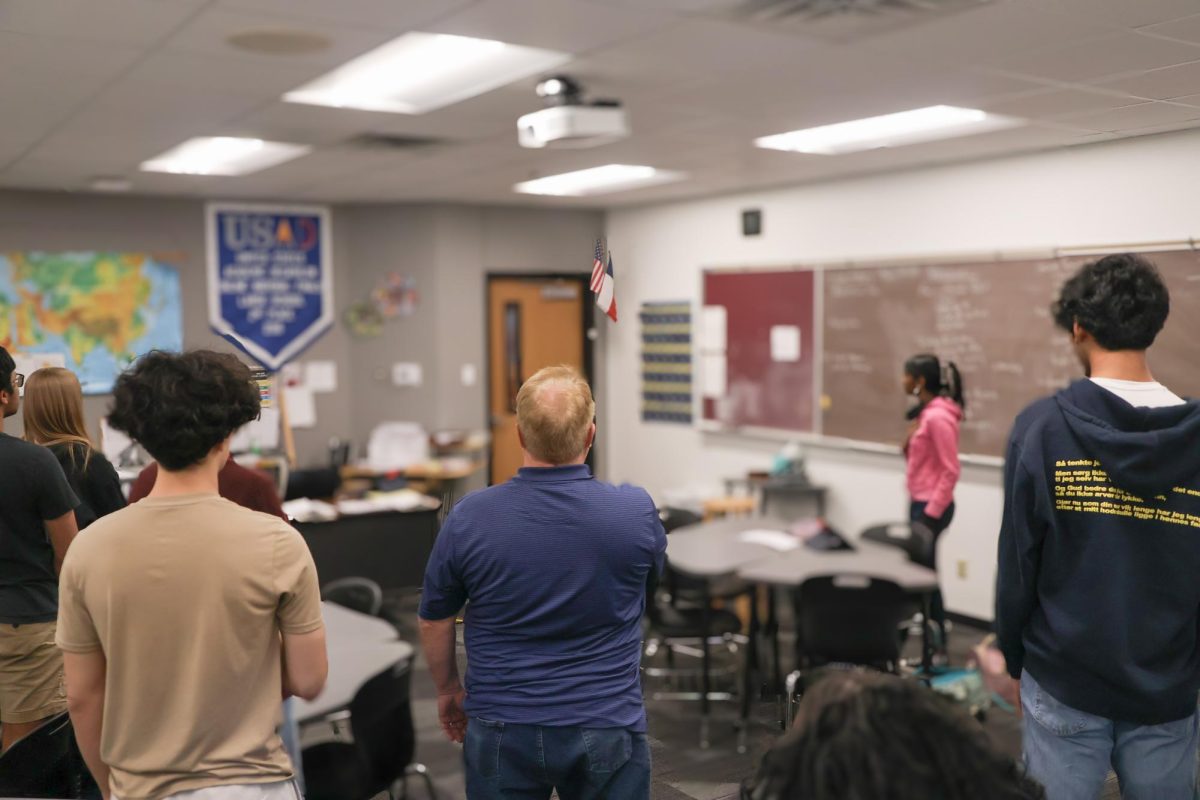

Any student athlete would agree: it is not always easy balancing education and sports. Some students play more than one sport and take multiple difficult classes, and oftentimes, their grades start to slip.

But, it is OK to fail, as long as they are performing well on the court, right?

Wrong. More often than ever before, UIL rules are being bent and stretched to accommodate student-athletes who are failing classes. These exceptions spread the message that education is second to athletic performance.

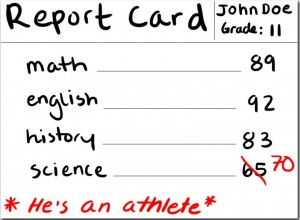

Picture the football player who is all too focused on the upcoming game and blows off his Thursday morning math test. He did not grasp the concept, and is now failing the class. The majority of students would flash into heart-attack mode, if they got an assignment covered in red ink.

Fortunately, this football player will still have a chance to make it on the field despite his failing grade. Too many times, this is simply the player’s main concern. UIL places rules that allow athletes to pay less attention to their classes by allowing them to round a 65 in a Pre-AP or AP class to a passing 70 through the use of a school-issued wavier.

You could argue, “They’re athletes. These athletes work hard during practice and sometimes they just cannot balance it all.” However, in the vast majority of the cases, any given student will rely on their intellect above their athleticism throughout their life.

Careers in sports are not reliable enough for students to make their priority, and these curves and waivers just feed the idea to student athletes that sports will carry them through life.

Too many times, small town athletes blow off their class load to accommodate long hours of practice. These athletes fail to see the bigger picture. They may be the star of their high school team and have their future lined up for them, but injuries happen. What one star player has relied on so heavily can be gone in a minute. Any injury, from a torn ligament to a paralyzing concussion, can strip a player from his scholarships and even his career. Of the 30 million school-aged Americans who play sports, 3.5 million are injured.

According to a study by Children’s Hospital, one of every four of these injuries will be serious. And in reality, people who base their careers on athleticism alone are standing on thin ice.

Even if the athlete avoids all injuries, there is no guarantee they will make it beyond high school level. According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), 0.03 percent of high school basketball players, men and women will make it to professional level. Even if an athlete is in the three percent of high school students to make college recruitment, it poses the question: then what? College is four years, and once your school hands you a diploma, your athletic career is over.

If a student’s failing grades are bumped up time after time, they’re being deprived of the life skills and lessons that will make them successful in other areas of their lives. The heavy class load and upper level content that makes high school curriculum so intense does more than pound information into our brains. The hours we spent working and learning are teaching us, as students, life skills that will help us be successful in the workplace and as adults.

Anyone who argues that we will not use math in life has never filled a tax return; just as anyone who bashes Biology has most likely never had to understand a medical condition. Sliding by in classes at the price of playing for a team can be costly in life.