“Guys, I’m such a big back,” I say, preemptively shaming my decision to grab another pizza slice before anyone else who is still finishing their first slice can make the comment.

Despite choosing to make myself the joke, I’m still flushed with humiliation when people giggle in agreement to my apparent gluttony of two pizza slices, but the punchline is never funny to the body you are making fun of.

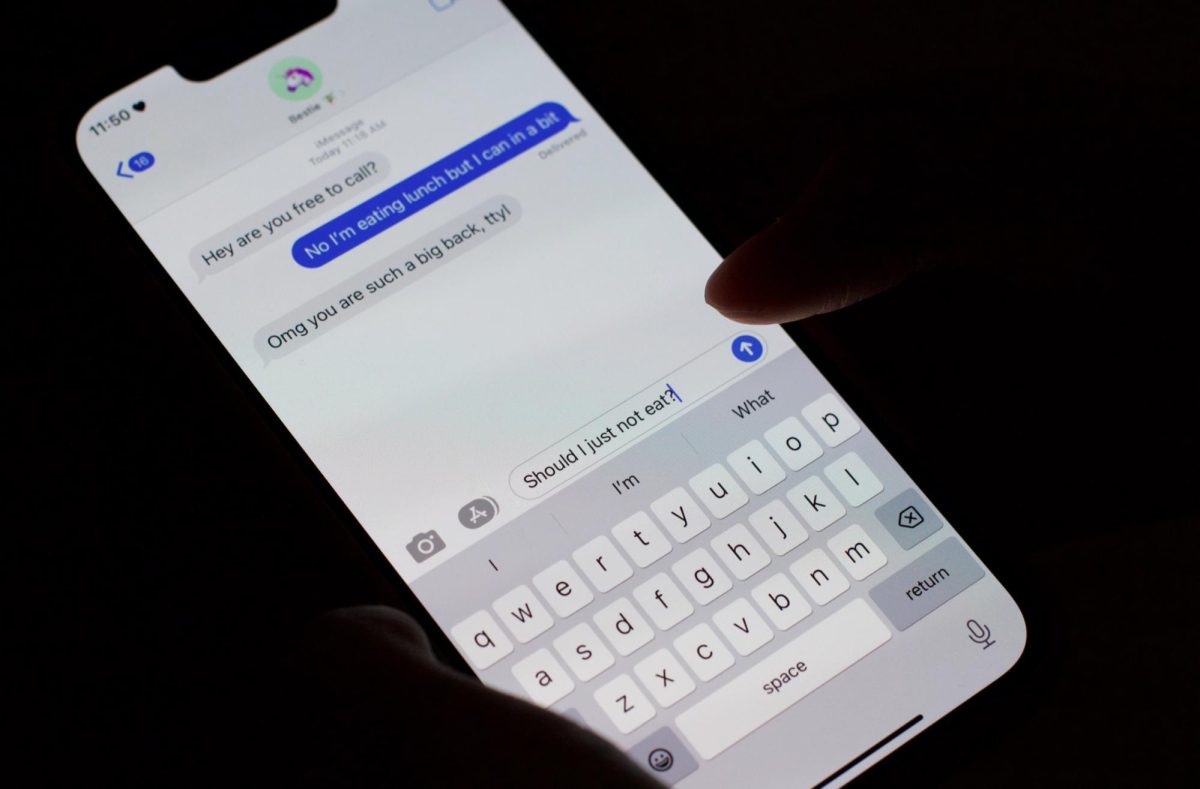

Situations like these are part of a phenomenon washing over teens using various social media platforms as they reenact the trends they see online such as a “big back,” “Ozempic allegations” and an obsession with being thin.

TikTok has taken the original meaning of many of the terms used in these trends and completely misconstrued them. “Big back” was once British slang term, referring to big butts. While it is hilarious, I know, it reveals the irony of changing beauty standards and true destructive nature of the trend.

Roughly 15 years ago, we saw the very first introduction to the beauty standard of thick bodies into the mainstream, led by celebrities such as the Kardashians, but this acceptance of new body types was limited to thicker women as long as they had small waists.

When the term “big back” captivated Gen Z, its meaning changed from admiration to shame of eating larger portions. A term once used to appreciate bigger bodies now denounces them, mirroring how society’s standards have shifted with these trends, cycling back to the late 1990s heroin chic aesthetic.

For those unfamiliar, the aesthetic is a style from the early 1990s fashion scene characterized by pale skin, dark circles, emaciated features, androgyny and stringy hair — all traits associated with abuse of heroin or other drugs.

We see this in popularized media today with artists such as Charli XCX who promotes heavy club culture and incredibly slim models like the Hadid sisters.

No beauty standard has been completely attainable without extreme measures, but with emaciated body standards, individuals have to push themselves to death in comparison to working out, eating more or having surgery that the curvier standard came with.

These trends have deadly and permanent consequences if we continue to allow it to resurface. For example, in the height of heroin chic, American supermodel Gia Carangu died at the age of 20 from AIDS complications as she was shooting heroin into her veins just to fulfill the fashion trend.

In 2024, we see illicit drugs replaced with prescription weight loss drugs like Ozempic.

Ozempic has not been FDA-approved for weight loss; it’s originally a treatment for type 2 diabetes but has become synonymous as a weight loss drug. The heavier dose, Wegovy, was only approved in 2021 and has only had minimal research on its long term effects.

Prescriptions for Ozempic had doubled in 2023 since the summer of 2021 to more than 1.2 million and it is part of the 301 active national drug shortages in this year’s first quarter. This means individuals across America are at risk of kidney failure, heart disease and stroke because of this shortage.

Teens have utilized disordered eating instead of prescription drugs, to achieve this body, and while some do naturally have it, it is not healthy to promote it as the standard when a majority of people can never achieve it without extreme dieting.

Ultimately, we need to understand the trends we promote and buy into having real practical effects, especially when it comes to beauty standards. The rise in body shaming trends have normalized an unrealistically thin body type, increasing disordered eating habits or reliance on weight loss drugs that have long-term detriments.

When you grab another slice of pizza or decide you’re full rather than making a self-deprecating joke or a punchline on fat body types, get more creative and make a joke that creates laughter instead of hair loss, teeth rot, malnourishment and the normalization of a beauty standard that kills.

Follow @CHSCampusNews on X.