Hands folded and eyes down, Chris and Martha Thomas take a deep breath as the video of the memories and passing of their daughter, 2011 Coppell High School graduate Ella Thomas, rolls once again.

In 2018, the Thomas’s lost Ella to suicide.

“Looking back on everything, I’m like ‘How did I miss this?” Ella’s brother, 2014 CHS graduate and New York Jets defensive tackle Solomon Thomas said. “How did I miss my sister being so sad? I was over here playing football while my sister was fighting for her life.”

On March 28, Chris and Martha Thomas, founders of The Defensive Line and parents to Ella and Solomon, gathered citizens of Coppell for a Parent University meeting at the Vonita White Administration Building.

Martha and Chris Thomas have worked to use their daughter’s story as an example for parents, a call for them to be aware and alert for their children. The foundation teaches parents how to recognize warning signs and strategies for open, honest communication.

“We’ve got a huge issue with our youth,” Chris Thomas said. “We have to find a way to get the right resources, policy, funding – whatever to stop it. It doesn’t matter what group you’re in, we just have to stop it. Any suicide is too much.”

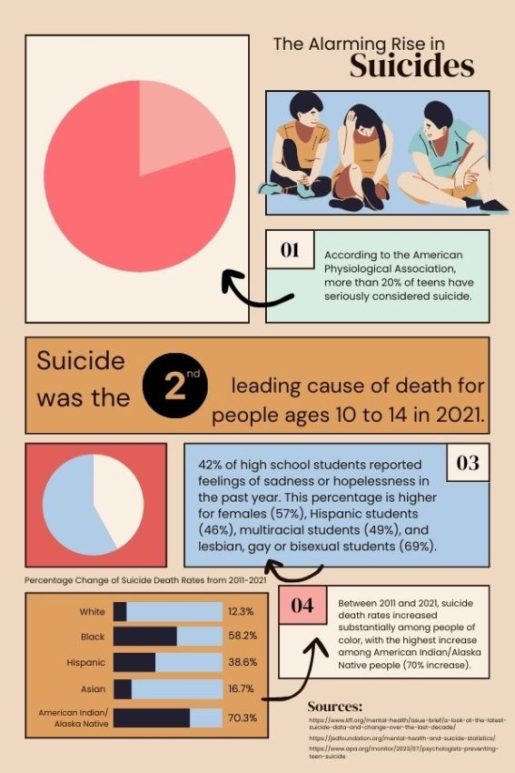

From 2021 to 2022, 42% of high school students reported feelings of hopelessness and 8.9% attempted to end their lives.

In 2021, more than 40,000 people died by suicide, almost a 5% increase from the previous year. As of July 1, more than 20% of teenagers in America have considered suicide.

Suicide rates among youth are rising faster than ever, particularly among females, the LGBTQ community and people of color. From 2011 to 2021 suicide increased substantially among people of color.

More than one factor

Walking the halls of CHS, you picture the quintessential high school life.

Students rushing to their next class, groups clustered up against the walls deep in conversation. Everything appears to be normal. But it is the feelings some of those smiles are hiding that can be much darker.

CHS consists of a multitude of diverse student groups, however, with that comes cultural stigmas centered around mental health and suicide.

“A lot of times, not just the Indian American community but also the Hispanic, African American and any Asian groups, the stigma might be greater or is greater,” Martha Thomas said. “There’s more cultural differences. It’s like how in the Black community, you have got to be strong. If you’re seen as weak, you could become vulnerable.”

Early in the school year, students are told that they have access to school counselors and other school resources if they ever feel overwhelmed. This idea is reinforced every year with the school’s suicide prevention week in September.

During each suicide prevention week, students watch a video in which they can see multiple testimonies from people who have struggled with depression and thoughts of suicide. At the end of the video, students take a survey or fill out a card that asks if they or anyone they know struggles with thoughts of suicide.

Where the problem with this arises is that CHS students are aware that if they answer yes to any of these questions, they could be called in for questioning by the administration and that their answers could be reported to their parents.

“There’s definitely a fear factor,” junior Meghan Chiang said. “A lot of times they’re scared they’re going to get pulled into the office, they’re scared they’re going to get questioned, they’re scared that their parents are going to get called, that their parents will get upset at them. ”

This is the same reason that many students are reluctant to discuss their mental health with school counselors. According to a survey done in 2022, 53% of students surveyed said they would not want their parents to know they are meeting with a school counselor or therapist. The prevalence of this in CHS has led to the normalization of suicide ideation dismissal of negative emotions.

While such programs are targeted towards teenagers and designed to initiate conversations, that goal often goes unrequited.

With a variety of AP, IB, honors and practicum courses and a range of hardworking students, the effort to achieve brings new challenges.

“You’re coming to a school with a lot of really good and academically strong students,” CHS Principal Laura Springer said. “Academics can’t control your whole life and making a B does not mean you’re a failure.”

This pressure to stand out, be ranked and maintain academics often becomes a path to self-comparison and emotional repression.

“There are certain kids in this building that are raised by parents who do not believe that you have time for any kind of mental health,” Springer said. “That’s not the most important thing. The social norm for some of these people is work, work, work through everything.”

The rise of phone usage among teens, especially during COVID-19, has contributed to feelings of isolation and suicidal ideation.

“With COVID-19, I think that that’s changed what mental health and depression look like,” CHS counselor Lindsey Oh said. “When we experienced COVID-19 it brought isolation to the surface, a different viewpoint.”

With teenagers having access to the internet earlier than previous generations, it has contributed to kids maturing faster.

“It feels like we don’t really have friends,” junior Samriddhi Baranwal said. “Everything moves to the internet.”

The widespread availability of social media, constant images flooding students’ screens and pressure to present a certain image of themselves has led to a snowball effect of anxiety and depression.

“In the past, everybody didn’t know about your life,” Springer said. “Everybody didn’t know every single thing about you. Everybody didn’t see you make a mistake and post it across the world for everybody to see. All of that kind of stuff is a pressure cooker for a kid who’s trying to cope with life.”

Narrowing into Coppell

Through programs in place such as SOS (Signs of Suicide), Coppell ISD prioritizes mental health awareness among students. SOS is a curriculum that is used from sixth through 12th grade. This is part of the TEC §38.351 Section (b) and Sub-section (c-4) requirement that all students receive education on suicide prevention such as warning signs, how to get help and how to let somebody know if you’re seeing those signs.

“It teaches students to let them know that you care about them because that can be a daunting conversation when a friend or somebody they are close to shares that they are having some thoughts of suicide,” CISD assistant superintendent of curriculum and Instruction Dr. Angie Brooks said.

Character Strong does not directly relate to SOS, but is an additional curriculum built into every third period class in CHS. It builds soft skills such as empathy and coping skills that allow students to understand responses towards their peers or their mental health.

“Often peers confide in one another and see things that we don’t see and we try to tell students to not keep secrets for their friend, and saying something when there are concerns,” Oh said.

To ensure support, counselors among CISD schools prioritize students’ comfort, always keeping a door open for potential concerns.

“[We] make our offices as safe and comfortable as possible because I know that it is scary to reach out to help students come in, but sometimes it’s more from friends that are concerned, and I always appreciate when friends are willing to say something,” Oh said.

In addition to school counselors, CISD provides direct access to licensed support counselors that provide one-on-one professional mental health support.

“Whether it’s mental health-related or just talking about interests, people feel connected to another person, feeling that sense of belonging, like they’re not alone,” CHS support counselor Kelly Spears said. “We need to be open to building new relationships and learning more about new people with a nonjudgmental stance, so when we ask someone, ‘Hey, how are you doing?,’ we expect to hear an honest answer.”

Focusing on one-on-one communication, CISD also gives all teachers training on how to effectively support different students with different backgrounds.

“When we identify with kids, we put at least one administrator and 11 educators in front of you during the school day that you feel comfortable with, and that you feel you can relate to,” Springer said. “Hopefully, when things start getting rough in your life, you will go to that person and say, ‘Can I talk to you?’”

Understanding the problems surrounding a student, stemming more from their mental health to potential internal pressures they may face, is CISD’s way of combating the academic pressure.

“We talk to parents about it, and some of it we can control and some of it we can’t because there are some parents who don’t care,” Springer said. “They want their kids to suck it up, they want them to get up to that top 10%, and it’s more important than anything else.”

Most of all, CISD emphasizes speaking up.

“People are embarrassed because they’re having those feelings and they shouldn’t be,” Springer said. “We all have stresses in our life, some handle it better than others. We have got to make sure that we get across that a person who’s going through mental health issues is not weak. It’s just a person who doesn’t have coping skills given to them yet to be able to understand what they need to do, to help get out of this pressure.”

In a school setting, help and support are what allow action to be taken before it is too late.

“It breaks my heart hard to think any of our kids want to hurt themselves,” Springer said. “It hurts me. I feel like we’ve failed in some way when they’re at that point, but we can control only so much.”

Our part in the puzzle

As a community, the roots for change lies in awareness and acceptance. From fellow classmates, teachers, neighbors or friends, change starts with the recognition of warning signs, and through it a drive for safety and help.

“If I don’t know that your child is struggling with something, I might not be able to give them the extra love and care that I could give them if I knew what your child is dealing with,” Pinkerton Elementary School physical education teacher Colleen Michaelis said. “I would treat that situation completely differently if the parent had reached out to me.”

This movement has been accepted, but not readily implemented across Coppell. Among high academic and social performance, it may be easy to forget the realities of individuals within the community.

“We have such high expectations within the community, even the word mental health, to say those two words is scary for some people,” Brooks said. “And that’s another reason why in my role and working together in the district, we have mental health written as a part of our district improvement plan.”

Helping students find a passion and realizing their potential promotes better mental health among kids, making them realize they have a purpose.

“I want us to constantly work with programs like our character program like we’re doing now, where we show students other kids who’ve had rough lives but have made it through it,” Springer said. “They all have to have a passion, they have to look for that passion and they have to let that passion grow.”

While such a big change can be daunting, it is not impossible. Though students are not always inclined to listen to the adults in their communities, their fellow peers and student leaders can help CHS take the next step in the mental health conversation.

“Who are the leaders of organizations, who are the top performing students at CHS that could stand up and say this is what we need to do for each other?” Martha Thomas said. “I don’t think anything ever happens overnight, but who are leaders in the community that could stand up and help parents to open up and listen because it does happen.”

Though cultural stigmas are not so easily combated, parents value their children and taking steps to help them can be crucial to saving their child’s life.

“I know other people’s parents are slowly changing and if other people can change, so can you,” Baranwal said. “A family’s understanding and a support group can lower this number. We can’t work our way top-down because we don’t have control at the top, but we can go bottom up, which is with our environment at school.”

Ultimately, greater acceptance in the community and more conversations with peers can begin to open the door to a brighter future. The promotion of a safe and healthy environment starts by distancing teens’ faces from their phones, engaging with real life and parents initiating conversations about mental health with their kids will promote a healthier, safer environment. One where no one ever considers the possibility of taking their life.

The Defensive Line works towards this goal with their drive towards suicide prevention. Through workshops and courses available all over the country, the Thomas’s strive to make an impact.

“Even though there’s a lot of stigma in communities, I know everyone’s parents want their kid alive,” Martha Thomas said. “No one wants to go through what we’ve gone through, no one wants that to happen. People love their kids, love their community and we can make that more visible.”

Follow Nyah (@nyah_rama), Aliza (@aliza_abidi) and @CHSCampusNews on X.