Greenberg carving biomedical pathway through hands-on research

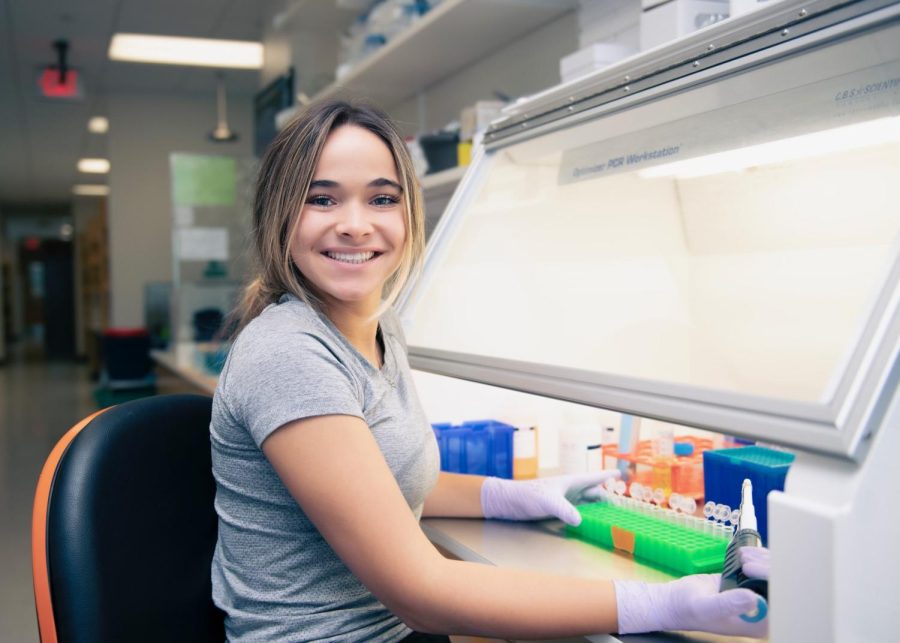

Coppell High School junior Hannah Greenberg processes DNA in an agar gel to a readable strand to be sent to sequencing at Monson neurology lab at UT Southwestern in August. Greenberg looks to pursue an occupation in the medical field. Photo Courtesy Hannah Greenberg

February 25, 2023

Coppell High School junior Hannah Greenberg’s summer job wasn’t your usual cashier or barista. Instead, her 9 to 5 emulated that of a medical professional, conducting paid research in a neuroimmunology lab under the advisement of UT Southwestern associate professor Dr. Nancy Monson. After countless hours at the lab studying autoimmune encephalitis, Greenberg was able to co-author a paper titled “VH2+ antigen-experienced B cells in the CSF are expanded and enriched for NR1-associated pediatric autoimmunity.”

What is autoimmune encephalitis?

It’s basically when the immune system of your body deals with viruses and attacks itself, and it’s specifically attacking parts of the neuro system, like the spinal cord and the brain. What we were specifically looking at is the neurons, so what transmits signals in your brain, and how a certain disease is attacking certain parts of the neurons and affecting the way they function.

How did you gain interest in such a field?

I’ve always been interested in the medical field, and that’s why this seems like a great step for me to get to try out and experience what research would look like and broaden my understanding of the medical field. I got into this through a couple of connections I had with a specific doctor and with people I know in their field. I’m very lucky to be able to work with [Dr. Monson]. She’s an incredibly esteemed researcher, and it was a great opportunity.

How did you prepare?

I jumped in the deep end; I went with pretty minimal prior knowledge. My first week in the lab was reading from a textbook and trying to orient myself. I was getting crash courses while I was there. I learned what I was doing as I went, which was a little scary, but then you got to learn while applying it, which I thought was cool.

I was terrified. It was the second week there and they were letting me do stuff on my own. And I was like “Why are you letting me do this? I know nothing, what in the world.”

What was your daily schedule at the lab?

About half of the day was learning and absorbing skills from other people in the lab. I would go watch [people], maybe two of my colleagues are doing something interesting that I would want to learn how to do or help out on. Then, another half of the day was working on pulling articles and sources for the paper, specifically.

What was the coolest part about lab work?

The coolest thing to me was something called immunohistochemistry. It’s when you are doing work with cells, but then you get to dye them and go under the microscope and see what you’re doing and see the fluorescent images. And in this case, it was to see if certain parts of the neuron [that] were getting affected. The visual part of that was really cool because this is cellular biology, so everything is so small [and you] can’t really see it. Getting to actually have it in front of you in neon colors was probably my favorite part.

Is this type of research the right fit for you?

I’ve thought about that a lot. The science I got to experience and research is super cool and super engaging, but it has made me realize that I do think the clinical one-on-one patient interaction of medicine is what draws me in. I’m a very social creature, and I think that’s an important part of what I want in my future.

How did you keep yourself from getting overwhelmed?

It was such a positive community. I was scared of seeming stupid, but I [came] with questions. I just realized that everybody was so kind that I kind of just let myself exist. And if I made mistakes, I knew there would be people there to kind of help fix it or support it. While I was allowed to do stuff on my own, I always knew that there would be someone else I could call on if something went wrong.

What advice do you have for future researchers?

You don’t have to know everything. If you’re reaching out to physicians or the research programs that CHS opens the door for, you can go into it and learn as you go. I think it’s scary, but all the professionals that are in this world are so happy and ready to teach, and even though it’s scary to ask questions, it’s the best thing you can do. Everybody just wants to help you get better.

Follow Sri (@sriachanta_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.