Read into it: young adult novels do not belong in literature classes

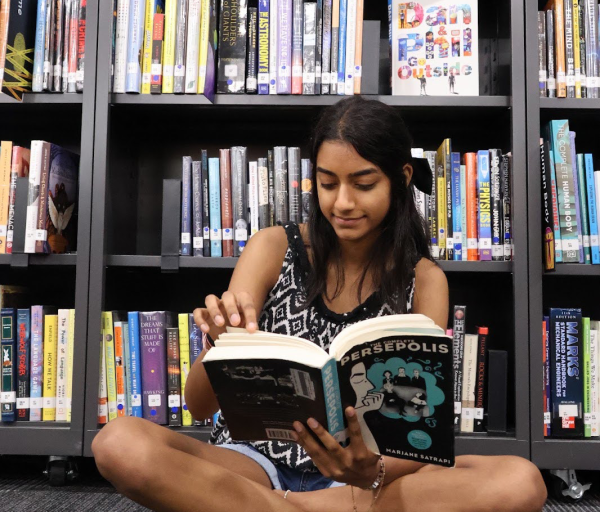

Young adult novels can seem to be a valid pick for analysis in English classes because they cater to high school students’ interests. However, The Sidekick editor-in-chief Anjali Krishna thinks YA novels don’t provide enough food for thought, rendering them useless in English classes.

The magic behind Donna Tartt’s famed The Secret History lies in the unlikability and wrongness of her six main characters – and just how confusingly lovable they are in spite of this.

There is Richard, desperate to find his people; Henry, maniacally obsessed with aesthetics; Francis, weak in every conviction; Bunny, a not-so-secret racist and homophobe; Charles, cruel behind his angelic mask; and Camilla, a woman, which in most literature counts as a fatal flaw enough.

It’s never stated that each character is so controversial, or that their actions are wrong. Even Bunny, who is so obviously hateful and insecure, is loved by those around him for his redeeming qualities. Tartt, and all other adult literary fiction authors, require us to draw our own conclusions and think critically about texts. In that is the difference between Tartt’s novel, as adult literary fiction, and something like Harry Potter, a young adult book series.

It’s something young adult books cannot do – leave so much up to a reader’s interpretation, since these books are meant for younger minds and made for enjoyment, rather than analysis. That is, in fact, the traditional demarcation between the genres. Adult fiction books hold more depth and thus, more room for the analysis English classrooms in America are trying to teach.

The point of high school English classes is to practice engaging with texts in meaningful ways and teaching students to take meaning from writing, then craft it themselves. Ergo, books that leave room for critical thinking and hold more material meant to be read into, are more effective in their curriculum. Then, why do we consider teaching young adult novels a viable alternative to teaching complex literature ripe for analysis?

The selected readings for literature classes are carefully chosen, each with deeper meanings ready for analysis. At Coppell High School, books for upper level literature classes are chosen by the class’s teachers together, and guided by lists from past years and the College Board in order to teach certain AP and Texas standards. Although the required readings are largely open to change, according to CHS teacher Alexander Holmes, the AP English literature teachers have yet to find a young adult novel to encompass these standards.

By their genre placement, young adult novels are not choice examples to teach such complexity,

Young adult novels are meant to be read alongside required reading and teaching in school, not taught to be analyzed in higher level literature classes. They may, however, be useful in teaching basic concepts such as plot structure and setting.

While we can hope that learning English is enjoyable or at least something students feel worth pursuing, switching curriculum to lower-level yet more purposefully fun books would not serve to motivate students already disinterested in the content, who typically dislike curriculum because it is school work, and instead cause intellectually curious students to lose interest for lack of challenging material.

Currently, the English literature curriculum at CHS focuses on these classics – and rightly so. Yet with students falling behind after a year of virtual learning in basic reading skills, discussion has opened up about worldwide curriculum switching to focus on basics and reengage students in learning with more fun content.

But young adult novels are not interchangeable with tried-and-true classics chock-full of analytical material. If the question lies in whether these classics are relevant to today’s English classes, a more viable substitution would be modern day literature by writers such as Kazuo Ishiguro, Haruki Murakami and Tartt, who broach modern subjects with nuance.

The Secret History details the story of a group of six Greek students, led on by their equally contentious professor, who make an attempt at an ancient Greek ritual and end up with dire consequences, ending up with an accidental murder, and a second “justified” murder to cover the past one up. The running theme underneath the plot is the utter ridiculousness of these twentysomethings engaging so obsessively in academia. They make justifications for murder and treat it as a necessary task, as something simple and sensible and able to be reasoned out.

It’s never said explicitly that this is wrong, and a debate between two characters on the subject comes to no real conclusion. It takes great talent on Tartt’s part to blur the lines so far between good and bad until we can’t tell who we are supposed to love or hate, and what we are supposed to agree with and what is morally wrong. To reach this conclusion, that their discussions are ridiculous and that they think their intelligence gives them the means to decide something like murder, takes a critical analysis that can only be taught in English classes.

In 500 years, the human race will not remember J.K. Rowling the way it does Shakespeare. It will remember the Tartts and the Sally Rooneys and the Margaret Atwoods, who wrote of inner meanings and deeper thoughts. That forces us to understand simply that certain words hold more meaning than others – and that learning about some provides value over learning others.

Follow Anjali (@anjalikrishna_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.

Anjali is a senior and this year's executive editor-in-chief of The Sidekick. As a writer in her third year on staff, she loves covering tennis, writing...

Avani Munji is a senior and the executive design editor for The Sidekick. Munji joined the program unintentionally, but found that The Sidekick was the...