Waging an inevitable war (Part 2)

Distrust of press leading to political polarization, threats to democracy

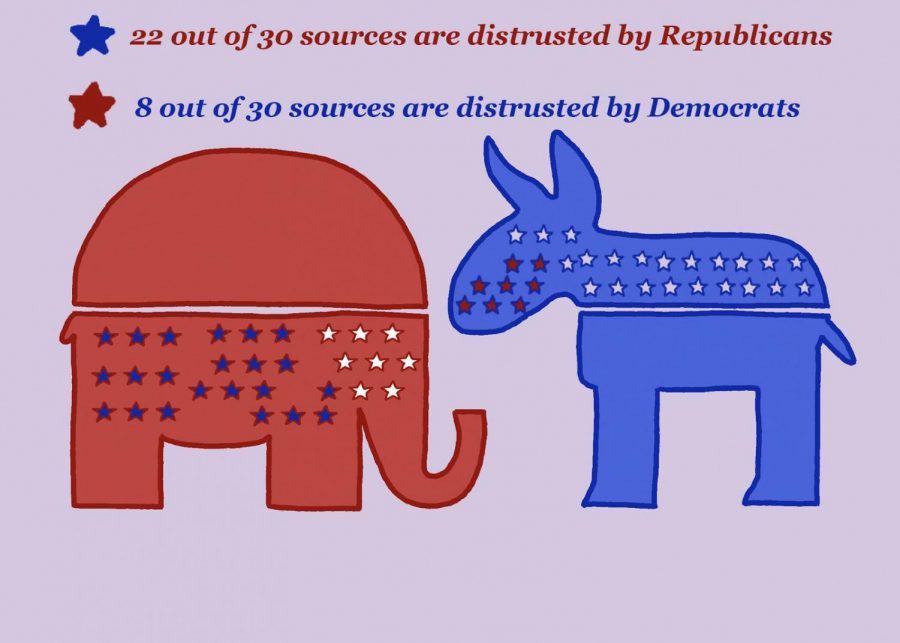

In a survey of 12,043 U.S. adults conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2019, it was revealed that Republicans had more than twice as much distrust when compared to Democrats in a sample of 30 news sources. As trust in the media has hit historic lows in the past four years, political polarization has been increasing. Graphic by Blanche Harris

February 26, 2021

Editor’s note: This is part 2 in a series exploring today’s news media and the impact of distrust on its consumers. Read part 1 here.

Deepening the divide

As trust in the media continues to falter, the armies expand and political divides are deepening.

“All these media companies are more concerned with clickbait articles and sensationalized news, which doesn’t help with factual reporting,” CHS senior Keertana Narayanan said. “People are then so reluctant to buy into this clickbait, partisan, not-telling-the-whole-story reporting and flock to whatever media site they think is best.”

Political polarization is not new, but as news sources have grown more biased, they have also cultivated more partisan audiences.

To The Trust Project founder Sally Lehrman, the increase in misinformation and explicit advocacy of distrust of the press is undermining the efforts of nonpartisan platforms, allowing for polarization to intensify.

“I wouldn’t say polarization is caused by distrust of the press,” Lehrman said. “It might be more that distrust in the press interacts with it because of the rise of misinformation and politicians actively saying they don’t trust the media.”

Former President Donald Trump’s condemnation of the press in the past has undermined public trust, especially in Republicans, allowing him to create his own narrative through social media and hyper partisan platforms.

“Anybody who wants to take control of society or the way we perceive events, a good way to do that is to knock down the press, because the press is independent and impartial,” Lehrman said. “Another piece is the rise of hyper partisan news and organizations that pretend to be news. In search engines, everything looks the same. It’s really hard to tell the difference between a real news story that’s produced with journalism and something that’s designed to convince you to buy into false ideas.”

Regulation is tricky. Navigating the line between reducing misinformation and restricting free speech is difficult and, if done incorrectly, can trigger outrage.

For example, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act currently ensures that social media platforms are not liable for illegal user content. However, as private companies rather than government entities, these platforms also hold the power to restrict speech as they see fit.

Section 230 has been a bipartisan concern, as many lawmakers believe companies should be held accountable for misinformation and disinformation spread on their sites. In the past year, Trump has publicly pushed for elimination of Section 230, claiming that it allows for political bias to increase, particularly after Twitter fact-checked, and ultimately, suspended his account.

Lehrman thinks government regulation of information could suppress the freedom of the press, decreasing transparency and increasing the chance of spreading government propaganda.

“Regulation is something we have to think really carefully about so that we do not unintentionally curb the free press,” Lehrman said. “What Twitter and Facebook did [on Jan. 6] was good. They needed to stop the spread of misinformation, and they honestly didn’t do that because of regulation but in fear of regulation. Whether we can trust any government to regulate is risky territory.”

KCBY-TV adviser Irma Kennedy disapproves of social media regulation as well, because she thinks it is not social media executives’ role to decide what speech should be prohibited.

“It certainly wasn’t friendly speech, it was ugly, and [Trump] went too far, but what makes Twitter the judge?” Kennedy said. “When we silence a group, we move closer to a government that has control over our speech, and that’s where the danger lies. If we look at communist countries, you cannot speak out without disappearing, and it causes concern because we’ve seen what these governments can do.”

Big tech companies were also major contributors to President Joe Biden’s campaign in November, and Kennedy thinks giving such platforms this power could allow them to impose political biases by regulating what information constituents can view.

“I recognize Twitter is not the government, but who will be silenced next?” Kennedy said. “It’s a very valid question we have to ask.”

In addition to fostering polarization, distrust of the press reduces the value of objectivity, allowing for not only opinion, but facts to be disputed.

“There’s a larger issue in the diminishing of a shared set of facts that we all then make decisions about,” The Dallas Morning News vertical news editor Beth Frerking said. “If we don’t even agree on what the facts are, it makes it harder to make decisions as a society.”

Threats to democracy

On Jan. 6, a large group of Trump supporters protesting the election results breached the U.S. Capitol, vandalized parts of the building and generated violence in an attempt to prevent verification of the Electoral College count.

As Congress was forced to evacuate its chambers in the biggest attack against the Capitol since 1814, threats against democracy and a peaceful transition of power progressed to attempted realities.

Distrust of the press influenced some citizens to turn to social media and right-wing platforms such as Parler, in which a lack of regulation with regards to misinformation made it much more difficult to separate fact from fiction.

“Journalism is vitally important in our world and in our society,” CHS Principal Laura Springer said. “If we have a democracy, we have journalism. If you decide you want a dictatorship, you have everything tunneled through one way, one person, one thought process.”

To Springer, journalism is synonymous with education, and she thinks an independent, honest press is a key component of democracy.

“I’m always going to be a supporter of journalism,” Springer said. “Uninformed people make poor decisions in life. They are led by people that are horribly out of touch with reality, and you end up with our democracy under siege.”

Springer thinks the Capitol protests were evidence of the dangers of losing trust in the mass media and turning to less verified and reputable sources for news.

“[The protesters] had absolutely been told something that was not true and led to believe they were cheated out of an election,” Springer said. “That all comes from the fact that if you just pay attention to one person, and you don’t check facts, you become distrustful of the news. You think all news is bad and all news is out to get you and that they’re always lying.”

Engaging with only one news source can allow individuals to entrench themselves in their own beliefs, and Springer recommends considering a variety of sources to reduce overall bias and develop a holistic understanding of issues facing the world.

“It’s easy to place the blame on someone else,” CHS associate principal Melissa Arnold said. “Unfortunately, honest journalists are getting the raw end of the deal right now. When you’re reporting in the moment, if you need time to confirm, another source is going to report it and you’ll lose the story.”

The aftermath of the election was a wake up call not only for journalists, but the public.

“Regardless of what you believe about the election, the lesson everybody should take away from that whole incident is that it is incumbent upon us as individuals to not take things at face value,” CHS AP psychology teacher Kristia Leyendecker said. “When we don’t think critically, when we don’t question, we see turmoil.”

Follow Avani @AvaniKashyap03 and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.