“Making a murderer” trial is a true crime

I first heard about Stephen Avery’s case in my fourth period English class. I had walked in on an early January day and found my classmates engaged in a conversation, but it was not about what everyone did over holiday break.

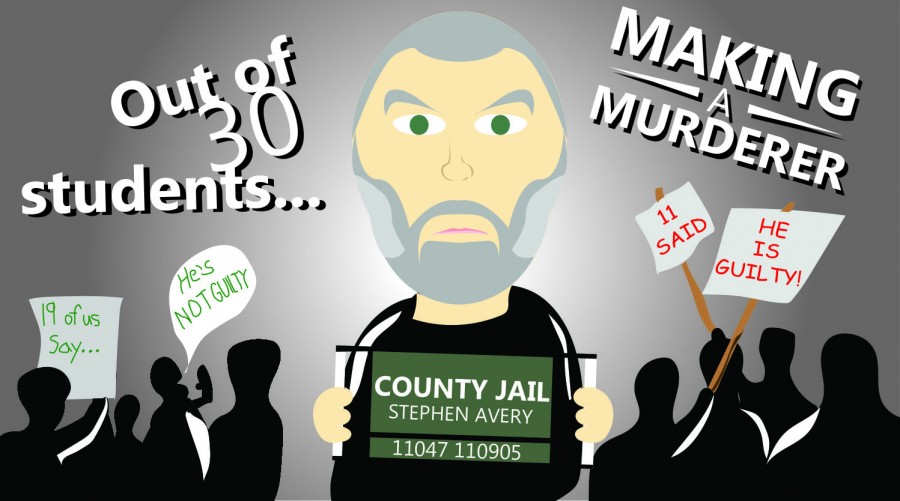

Many of them had binged watched the 10 episode Netflix miniseries, “Making a Murderer,” and were arguing about whether or not the show’s subject, Avery, was guilty of murder. The fact that the innocence of this man was so disputed, even by my teacher who joined in on the conversation, led me grab the remote and see what was perplexing my peers.

For those unfamiliar with the series, the documentary is centered around the twisty and terribly ironic life of the Wisconsin resident, who was falsely imprisoned for 18 years, only to return for a life sentence two years later on charges of murder. By weaving together interviews of those close to Avery, and footage from the months long trial, the creators were able to create a pretty convincing case in Avery’s favor – the show garnered a petition to the White House with nearly 130,000 signatures in under three weeks.

After watching the trial, observing over every piece of provided evidence and listening to testimonies from both sides, I finally came to the conclusion that I had no idea whether Avery was guilty or not. However, I was sure of something, his trial was plainly unfair.

In Avery’s trial, the defense brought to light information that could possibly point to corruption by law enforcement. For example, a key to the victim’s car was found by police in Avery’s home in clear view after it had been searched six times, and a vial of Avery’s blood had appeared to have been tampered with.

There is also the condemning eyewitness statement from Avery’s mentally-deficient nephew, Brendan Dassey, also currently serving a life sentence, which is surrounded by evidence of foul play by authorities, such as coercing statements and conducting off-record interrogations.

According to The Innocence Project, an organization which recognized Avery after his wrongful trial in 1985, improper forensic evidence played a role in the cases of 46 percent of exonerees, whether it be by incomplete analyzation, or outright forensic misconduct. There is also currently no entity that establishes whether or not drug tests are reliable before they are allowed to be used as evidence in court.

False eyewitness testimony was the leading cause of wrongful convictions, with over 70 percent of exonerees affected by faulty statements. Further, 31 percent of exonerees were affected by false confessions and incriminating statements.

The Innocence Project (TIP) estimates between 2.3 percent and five percent of all prisoners in the United States are innocent. While I do not believe Avery should be immediately exonerated based on what the documentary has presented, I do think he deserves the right to an honest, more ethical trial.