Separate playing fields: The systematic gender stigma in sports

May 19, 2023

The clock reads 8:30 p.m. as the Coppell boys basketball team jogs onto the court. It’s a cold and rainy February night at Coppell High School, but an incandescent glow radiates inside the arena. There is no empty space in the student section – everyone is crammed into the stands, watching the court intensely.

An hour earlier the clock read 7:30 p.m. There were two people in the student section for the girls basketball game.

Identifying the roots

It is no secret that women’s sports have always struggled to draw a crowd at games. Women’s teams struggle to find ways of incentivizing people to come support their teams, sometimes resorting to borderline desperate and degrading tactics. According to The Atlantic, when Kansas State passed out free bacon at one of its women’s basketball games, student attendance more than tripled.

Furthermore, difficulty drawing crowds doesn’t end at the high school or collegiate level, it continues into the professional level at the WNBA.

The NBA record for most fans in attendance at a single event remains 108,713, which was set at the 2010 All-Star Game held at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas.

What does it take for people to pay attention to women’s sports; bribery, giveaways, a playoff run?

According to The Atlantic, analysts say that the small number of female sports journalists has led to less overall coverage of women’s sports, and that the limited media attention also takes a toll on these teams’ popularity.

All of this goes to say that the entire process is cyclical and systematic in society – less female sports journalists means that there is less coverage of those athletes and teams. Consequently, if there is less coverage, there is less popularity for the sport and it becomes harder for younger generations to visualize a successful career in that field.

In a field that repeats a cycle, it appears that there is no room for change.

Bayley Zarrehparvar, a 2011 CHS alumna, was a staff member on The Sidekick and KCBY-TV and is now an ESPN associate producer.

“The disparity is there and it’s pretty apparent,” Zarrehparvar said. “Some of the disparities you’ll see happen in just the ability for these games or meets to be broadcast.”

According to Zarrehparvar, the difference not only lies in the women covering these events but how they are covered: you have high profile linear networks streaming men every week in prime time slots for viewers, which leads to differences in the audience, coverage and budget.

When high profile networks broadcast women’s sports less often, these sports don’t receive as big of a viewing audience and therefore have lower popularity and don’t receive as much of an opportunity to succeed as male sports and athletes.

“When you look at the kind of opportunity past collegiate sports, that’s another place that the equity lacks,” Zarrehparvar said. “A fraction of those athletes become collegiate athletes and then an even smaller fraction of those collegiate athletes become professional. 100% of the athletes I cover for women’s college gymnastics, when they compete a final routine at the NCAA Finals, it is their final routine. They don’t go on. There’s not a secondary thing for them.”

When there isn’t a drive for a sport at the national level, how can high school and collegiate athletes see a tangible future for themselves in their sport?

How CISD is impacted

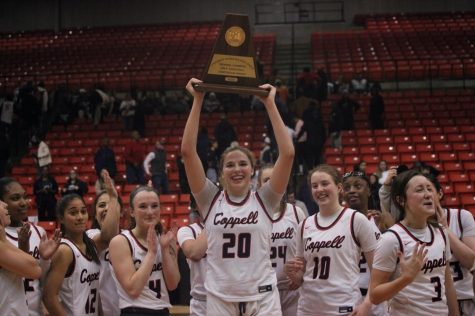

In March, the girls basketball team advanced to the Class 6A semifinals for the first time in program history, drawing in the most recognition and attention the program has ever received.

The Cowgirls never drew a crowd in the student section until it advanced to the Class 6A State Tournament and the Coppell boys basketball team did not.

“I feel like we continue to not be respected and it frustrates me, because look at our kids.” CHS Principal Laura Springer said. “We had some of the greatest female athletes we have had and if you look at every program this year, we had more girls programs go to state than boys this school year, but nobody is recognizing that nor posting it anywhere. If we had that many boys programs go to state, it would be everywhere.”

According to Coppell girls basketball senior guard Waverly Hassman, the further the Cowgirls advanced into its playoff run, the more the way they were treated began to change. All of a sudden, the team was invited to school board meetings, they were recognized throughout the community, but not so much by their fellow classmates.

On a typical Coppell home basketball game night, the girls game precedes the boys game.

At the girls game, the stands are usually filled with teachers, parents and younger members of the community, but the student section is sparse throughout the entire game, if that. As the fourth quarter of the girls game rolls around, more students begin appearing in the crowd, waiting for the boys to take the court.

“On the high school level, it’s definitely about school support, and school spirit,” Hassman said. “The guys play after us and a lot of the time, the fourth quarter rolls around for the girls’ games and the student section will start to fill up. Some people see that as, ‘Oh, well they’re coming to support the game.’ No, they’re coming to support the boys game. They just came a little too early and they have to watch the end of our game. There are still parents and little kids from the community that want to watch us play, but it is definitely frustrating when your student body doesn’t seem to show the same support.”

However, as the girls basketball advanced into the playoffs, the student section grew each game.

“We joked around that the parents and the occasional boyfriend were all that we had for a long time, and now we have huge crowds at the playoff games,” Coppell girls basketball coach Ryan Murphy said. “So it was a home court advantage at every single playoff game that we played.”

The girls basketball program is not the only female sports program in Coppell ISD experiencing lack of support in the student section.

“In Coppell, people are always going to go to the football games, whether they’re good or bad,” Zarrehparvar said. “But that’s the telling point, right? Win or lose, people are going to go to those games. Whether it’s because of tradition, the social aspect or a need to feel like you’re doing the right thing on a Friday — people are going to go — but the statement doesn’t ring true for a number of other sports. Especially on the women’s side.”

If it’s all about school spirit and support, then why is there still such a large disparity in the student section between male and female sports?

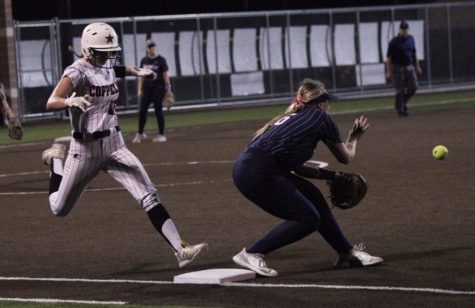

“I have covered a good amount of baseball and softball games,” The Sidekick sports visual media editor Olivia Short said. “In the same week, when I covered baseball, the entire student section was full – people from every grade were there, there wasn’t a single seat that was open for both schools – when I go to softball, it’s only parents, to the point where there are whole rows open or only one person sitting in them. I would say there were a total of 30 people there, from both teams. It was really hard to watch because both the baseball and softball team work hard and you only see recognition on one side.”

In order to draw a crowd in the student section, female sports and athletes have to work harder to advertise when their games are.

“There is a lot more advertisement for the boys games, there are more hype videos made, there are signs posted outside reading ‘boys home game tonight,’ even when there is a girls game too, ” KCBY sports director Arabelle Warren said. “Until they started the playoffs, there was really no outward support for them and they had such a great record the whole season.”

Additionally, some think unaffiliated Coppell sports accounts are part of the issue.

According to Warren, the Coppell Barstool page is used by many Coppell students to access the schedule for male athletic events. However, the account never posts anything about the female sports in Coppell.

Furthermore, according to Short, the only time girls have been posted on the account is to call them out or make fun of them. Not specifically female athletes, but girls in general.

Throughout the girls basketball team’s successful season, none of the playoff games or even the state semifinal game was posted about on the Barstool page.

“On Instagram pages that aren’t affiliated with CISD, the accounts post baseball, boys basketball and football game times, themes and locations,” Hassman said. “I’ve never really seen a girls game — whether it’s for softball, girls basketball, girls soccer — posted on there, even if it’s a playoff or state semifinal game. Those sports have never really been broadcasted on the account, which I think would make a big difference because a lot of people in the student body follow this account.”

Hassman described how multiple times she’s had conversations with male friends and tried to convince them to come to a girls game. Hassman recalls once the Cowboys played in Marcus and the Cowgirls played at home, yet her friends were still more interested in attending the boys basketball game.

“We have to go the extra mile to advocate for ourselves,” Hassman said. “I think that goes for women in all sports. We take time out of our day to post on our own social media because we know that no one else is going to post it besides our school team and stuff. We have to go above and beyond to be amazing for people to even notice.”

One common argument made to explain the crowd disparity between boys and girls games is the intensity of the game. Oftentimes, people argue that a girls game is slower and less intense, which is an invalid argument for the Coppell girls basketball team.

“To make the statement that girls’ games are less intense, is honestly just moronic,” Hassman said. “Especially when you show up in a state final game and lose by one point, that’s an incredibly intense game. Everything is on the line at that game.”

The overall record for the boys basketball team for the 2022-23 season was 24-11, whereas that of the girls was 38-4. During their playoff run, the highest point gap between the Cowgirls and their opponents was 13 points and the lowest was one point during the state semifinal.

Moreover, according to Coppell athletics director Kit Pehl, the boys basketball team has not had a state run since 1999.

“The boys have a safety net,” Hassman said. “They’re always going to know that people are going to show up to their game, but the girls basketball team doesn’t necessarily have that. Sometimes the team feels like we have to be amazing to have people show up when the guys can be mediocre and still have a huge turnout. I honestly can’t tell you why that is, but it is really frustrating.”

Breaking down the barrier: better, but not enough

“The women that have come before me and the women that came before them had it a lot worse and have blazed trails and done the hard work,” Zarrehparvar said. “My generation of women is continuing that work and continuing to cut down trees, bushes and weeds to make a really great path for the women that continue to come after us.”

Change is often hard to enact and slow to implement, but advancements in reducing the gender disparity in sports have been made and have brought about that change, on all levels of play, not only at the collegiate or professional level.

“We need to make sure that Coppell ISD supports any girl that wants to pursue athletics,” Springer said. “It may be just to the high school level, but we are going to give her 110 percent in that pursuit to be able to shine and be a woman that is going to be amazing in her future.”

District leadership shares Springer’s hope.

“When a girls sport is doing really well, it gives me a ton of hope for what I want all of our sports to look like and how I want them to be supported,” Coppell ISD Athletics Director Kit Pehl said. “The way the girls basketball run happened helps break a stereotype instead of contributing to one.”

According to Zarrehparvar, for several years on the men’s side of the College World Series, dark days in television existed – days in which athletes, coaches, reporters and broadcasters could rest in between games – and were built into a team’s schedule. However, only until recently did the Women’s College World Series implement this concept as well. Female athletes had to advocate for these important days in the schedule where they could focus on recovery rather than finishing a game late and then playing early the next morning.

Regardless of how slow the change came about, it is there and important to recognize as it created more equity in the realm of collegiate athletics.

Another policy that has created change is Title IX, an amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965.

Title IX gives women athletes the right to equal opportunity in sports in educational institutions that receive federal funds, from elementary school level, to colleges and universities.

Elizabeth McQuitter played basketball when Title IX was implemented in 1972 and played in the Women’s Basketball League, which only lasted three years. She is a trail blazer for womens basketball and played in the first professional women’s basketball game in the United States.

“The culture surrounding women and sports has changed tremendously over the years,” McQuitter said. “Doors of opportunities are open now that weren’t back then. I see girls now making salaries and women officiating men’s games. It’s not an equal opportunity as far as finances are concerned, but it is a lot better than what it was.”

The amount of opportunities presented to female athletes has increased since the implementation of Title IX and other policies aimed towards instituting equity, but there is still a long way to go.

“We get complacent because we get to fly like the guys, we get sweats like the guys and we have a beautiful gym like the guys,” McQuitter said. “We’re molded into this false sense of security that everything is equal. But the pay isn’t equal, the funding isn’t equal. [To combat inequalities within sports] you have to first: be aware, and second: don’t get complacent. Keep up the fight, keep pointing it out.”

For this story, The Sidekick reached out to several coaches for both male and female sports at CHS: girls basketball coach Ryan Murphy, boys basketball coach Clint Schnell, softball coach Kimberly LeComte, baseball coach Armando Garza, girls soccer coach Craig Abel and boys soccer coach Stephen Morris.

Hi Coach ______,

My name is Ava and I’m a staff reporter for the Sidekick. I’m currently writing a story about some of the disparities between womens’ sports vs. mens’ sports, and I would love to get your input.

I was wondering if you would be willing to conduct a quick interview about this?

Thanks,

Ava Johnson

The coaches that responded included: Murphy, LeComte and Abel — all of the female sports coaches.

It is one thing to read about someone experiencing something and another to experience it yourself — it makes the experience more raw and pressing. After reaching out to other female sports reporters and broadcasters, The Sidekick discovered that many of them experienced similar situations, whether they write for a high school newspaper or ESPN.

“There’s always this air that lingers that I’m being treated like I don’t know what I’m doing.” Short said. “You see a camaraderie with the male reporters and the players. When it gets to female reporters, you see more of a blunt attitude. That’s not always the case, you definitely see on the sidelines of how male reporters have a friendly relationship with players and then it seems like men are only going to talk to me if they want something from me.”

In addition to members of The Sidekick staff, members of KCBY have had similar experiences.

“From what I’ve seen, there are definitely more male reporters, more respected male reporters,” Warren said. “As a female being less respected in the sports regime, you have to work harder and know what you’re talking about, or at least seem like it.”

But the experiences don’t end there—they continue on to the professional level.

“There have been a number of situations in my career where I’ve had to work harder,” Zarrehparvar said. “I’ve had to study harder, I’ve been passed over for things and been ignored in a situation where I knew I knew what I was talking about. My male colleagues don’t always have to deal with that.”

Springer played basketball from a young age, throughout college at Mississippi State, then coached girls basketball at CHS.

“I get frustrated at the gender inequity in the fact that most people assume girls are not real athletes; That they don’t have to work as hard as guys or aren’t as talented as them,” Springer said. “But, we have to have more talent to play our game.”

The girls basketball program at CHS has been extremely successful, not only during their playoff run, but throughout their entire season. Still, players on the team feel a lack of support.

“We are one of the most successful teams to ever walk through Coppell and to still have this issue is very frustrating,” Hassman said. “I really hope that the support doesn’t end here. The team next year might not have the same record, but it’s still the same program, it’s still the culture that we created. The only thing that changed was the girls out there.”

The support that the Cowgirls gained during its playoff run is promising for next season and will continue, but nevertheless, it took a while to reach that level of support. The fact still remains that each step along the way until they secured a spot in the playoffs, the Cowgirls had to watch their sparse student section fill up as the boys games each night drew closer.

However, the crowd that the Cowgirls drew at their playoff games was always as big, if not bigger, than their opponents.

Additionally, several players on the boys basketball team reached out to the Cowgirls throughout its playoff run and offered to scrimmage and practice with the team to help switch up the feel of the game and unpredictability of their opponents.

Coppell junior forward Antonio Romo was one of the players that practiced with the Cowgirls during this time.

“It was definitely eye opening because we went into it and thought we were going to dominate,” Romo said. “Then, I remember a couple plays where they dropped two three’s in a row and the coaches were laughing. We were looking at each other after and it was humbling.”

Romo and the other boys continued to make the journey to each of the Cowgirls’ playoff games, spreading word of the Cowgirls’ skill and their experience playing with them, drawing in more people to the student section each time.

“Our society, not just here in Coppell, has always been super supportive of male athletics and we are working up an uphill battle right now for women in sports all over the place,” Coppell softball coach Kimberly LeComte said. “There have definitely been some huge accomplishments in female sports recently and I think we’re on the right track to really propel our games.”

“There’s an innate quality about men and sports and people just believe that they know what they’re doing,” Zarrehparvar said. “The day I’m excited for is the day the question doesn’t have to be asked ‘what have you had to do differently than your male colleagues?’”

Follow Ava Johnson @Avakjohnson4 and @Sidekick Sports on Twitter.