Swift is golden on ‘Red (Taylor’s Version)’

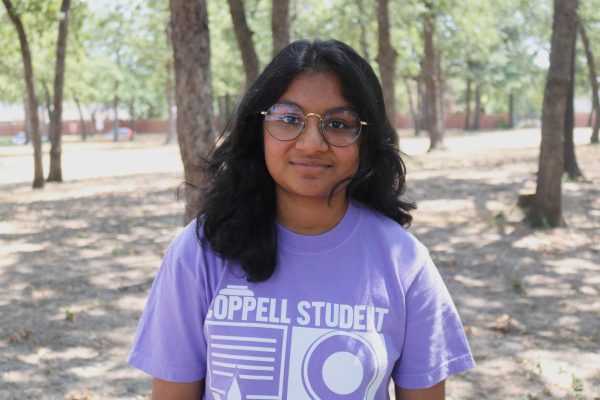

Singer Taylor Swift released Red (Taylor’s Version), the second of her re-recorded albums, on Nov. 12. The Sidekick editor-in-chief Anjali Krishna writes about how the album is different from the first recording and why it doesn’t have the same impact as the original from 11 years ago.

December 5, 2021

Taylor Swift never forgets a thing. Not her scarf, left in an ex’s drawer with other things long passed, not the note on the door with a joke she made and not a new guy pulling out a chair for her on the first date.

In her original Red, Swift draws on her ability to pinpoint these moments, the ones of collapse or brightness, with painstaking exactness. It is a relationship in retrospect – current heartbreak on full display. Red (Taylor’s Version), the second of her re-recorded albums, is less precipitous; less heartache, more explanation. There is no longer a nostalgic, achy feeling of confusion and misery, and her vengeful moments and witty one liners come off less cutting for it.

Red, listened to in order, allows a realization: each track adds up to the story told in “All Too Well (10 Minute Version).” It is sped up and from the get-go, less sad. For fans of Swift, it holds possibilities for years of analysis.

For fans of her lyricism, it has “You kept me like a secret, but I kept you like an oath” and “Just between us, did the love affair maim you too?” Gems like this are sprinkled throughout as she decimates an ex, taking it from a tone of heartbreak to one of utter outrage. It is too personal to be anything more than that, and the speculation about her personal life emerging from the more definable moments overtakes the feeling of reminiscence in “there we are again in the middle of the night / We’re dancing ’round the kitchen in the refrigerator light.” Even 10 years later, the hurt is still there.

But the youth in Swift’s voice is lost, and so is the grit that came along with 2012 sound quality. Her pop tracks lose their charm with that, and they don’t feel like respites to the fitting wistfulness of the album, or part of the wild slew of emotions Swift was feeling when she wrote the record originally, but rather beneath her ability.

The cool millennial vibe that is lost in “22,” appears, oddly enough, in “Nothing New,” one of Swift’s best tracks to date. She’s 32 when she sings it, but “How can a person know everything / at 18 and nothing at 22?” feels painfully young. It is ironic to hear her trade prescient verses with indie pop phenom Phoebe Bridgers after Swift’s 2016 scandals, wondering “if they’ll miss me / Once they drive me out.”

Though the new production fails to convey emotion in parts, the title track, “Treacherous” and “The Last Time” turn into experiences: heady indunations of sound. It feels like Swift is into it, and the greater backing vocals in “Treacherous” impose an intoxication into the track. As “two headlights shine through the sleepless night / and I will get you, get you alone,” Swift zones in masterfully. What could have come off excessive in an attempt to feel sensational, (as in “The Way I Loved You” and “Love Story” in her first rerecording) stays muted in both tracks.

“State of Grace” and “Holy Ground”, both quintessentially Swiftian tracks, are the opposite. Swift’s voice is too loud and the backing drums too inebriating. Though she screams with just the right amount of devotion, her hopeful lyrics (“Mosaic broken hearts / But this love is brave and wild”) are drowned out. “Holy Ground,” is slowed down, and the rushing feeling of a new relationship, the one she captured in the original, is lost.

Much of her anger is now spitting as she replicates resentment that doesn’t feel natural. But on the final verse of “Sad Beautiful Tragic,” groaning background vocals compete with her voice. As she forces “Would you just try to listen?”, it’s like Swift is begging right in front of us.

In her original Red, when Swift proclaimed “This is a golden age of something good and right and real,” we were all rather confused. When she wrote her original Red, Swift was 22, heartbroken and growing into superstardom. Love, for her, was devastating, torrential and all-consuming. What exactly is so good and right and real in her relationships falling apart and breaking wide open in front of the world?

In Taylor’s Version, we know exactly what she means; we know she’s been through her heartbreaks and now has her fairytale ending. As she said on Lover, “I used to think love would be burning red / but it’s golden.” And where she should be, and where she shouldn’t, Swift burns golden on Red (Taylor’s Version).

Follow Anjali (@anjalikrishna_) and @CHSCampusNews on Twitter.