Biggest enemy in mental illness to defeat is denial (Part 1 of 2)

When sobbing uncontrollably in her mother’s car every morning before school became a regular occurrence in Coppell High School junior Jane Doe*’s life, she knew something had gone seriously wrong.

At the time, Doe was only 13 and in the sixth grade, an adolescent just entering middle school. This time period is notorious for the violent mood swings and awkward hormonal changes, amongst other havocs, it wreaks upon teenagers. Doe does attribute a portion of her emotional struggles to such experiences.

However, there is much more to her story.

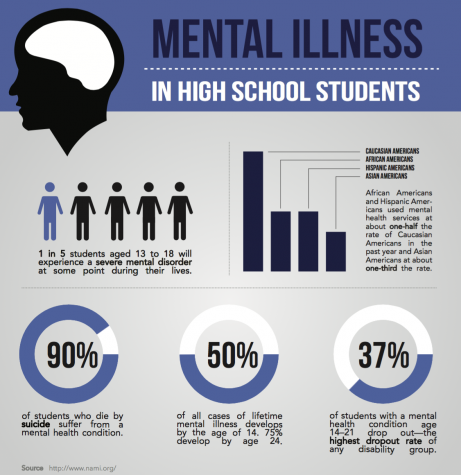

Graphic by Kelly Wei.

Doe has an extensive family history of mental illness: her mother battled postpartum depression and her grandparents from both sides also suffered from depressive behavior. This rendered Doe especially predisposed to developing the symptoms she did: stress, frustration, sadness and a seemingly ceaseless wave of general unhappiness.

“I started feeling really angry a lot of the time,” Doe said. “For a long time I was just bottling things up inside.”

Despite all of these signs, it wasn’t until over a year and a half later that Doe was finally diagnosed with clinical depression and social anxiety.

Unfortunately, this is not an uncommon story for many teenagers to tell. There are long delays between the first appearances of mental illness symptoms and the receival of effective treatment–only half of those affected reach out for professional help at all.

“Some view not being able to do everything at a high level as a weakness,” said Las Colinas cognitive behavioral therapy counselor Sarah Walker, who is also mother to a Coppell High School student. “There is still a stigma in our society about mental illness. Many feel ashamed, afraid and embarrassed admitting that they need help.”

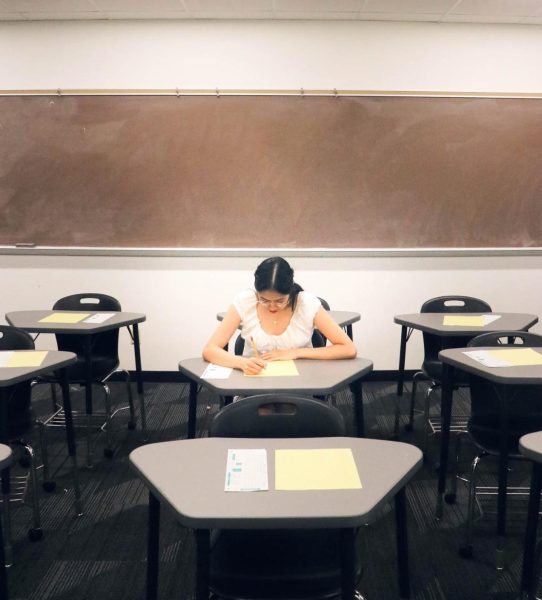

This is especially relevant to CHS students, many of whom find themselves unwitting participants of a cutthroat academic culture. While rigor and an advanced learning environment are able to motivate students to succeed, Doe can also attest to the detrimental effects of having too much pressure to perform well.

“I was in band, I was in choir, I was in higher-level classes and I was in theater–all at the same time,” Doe said. “That’s not something [I could] do – my stress was high, my anxiety was high.”

CHS AP Psychology and IB Economics teacher Jared Stansel agrees that the workload and high-achieving culture at CHS plays a significant role in the mental health statuses of students.

While it can be undeniably challenging to work against the development of mental illness, having to accept the reality of having one can be just as daunting, if not more. The demanding school atmosphere driven students are exposed to frequently compel them to dismiss their mental health issues in favor of simply ‘working harder’ or ‘sucking it up’.

“Some students try to internalize these stresses and they try to fix things [themselves],” Stansel said. “They think that, ‘if I rely on someone else, then that confirms that I’m lesser-than, so I need to work this out myself’. That can be very detrimental, because it compounds upon the anxiety that they’re already feeling. It just makes the situation that much worse.”

Doe, diagnosed in seventh grade, spent nearly four years regularly seeing a therapist to treat her depression and anxiety before being prescribed antidepressant medication in the ninth grade. Now, a junior, she has just been recently taken off her medication and is on a steady road to full recovery.

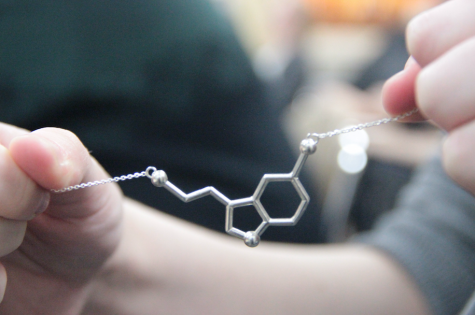

Doe wears a necklace in the shape of the chemical compound for happiness, serotonin. It is one of the many small ways Doe celebrates her journey to self-love and peace.

Looking back, Doe recalls similar emotions of reluctance to acknowledge her mental health issues and pay it the proper attention needed, for fear of what others would think of her.

“It was hard [to speak up about my depression], because everyone saw depression as an attention-getting thing and so I was scared that by saying these things [people would think] I was just making things up in my head for attention,” Doe said. “You know, ‘I don’t actually feel this way’, ‘this isn’t actually a problem’, ‘everybody feels this way, I’m just making a big deal out of it because I’m dramatic’.”

In the end, however, she discovered that the only way out is by facing the problem head on.

Today, Doe can be seen wearing a pendant necklace in the shape of the chemical compound serotonin, the chemical in one’s brain responsible for emotions of happiness.

It is one of the many small ways Doe celebrates her journey to self-love and peace – one that would not have occurred had she refused to accept and acknowledge the dark place she fell into so many years ago.

“The sooner you can get the issues addressed, the higher likelihood that more serious ones can be prevented,” Walker said, advising those currently suffering from mental illness.

Doe delivered a similar message of encouragement and reassurance.

“When I got on medication, I wasn’t expecting to get off, so when I did, it was amazing,” she said. “You don’t have to think you’re going to succeed in the beginning, but you have to try. That’s the biggest thing: you have to try.”

* – For privacy purposes, a pseudonym has been used in place of the source’s real name.

Follow Kelly Wei @kellylinwei

Kelly Wei is a senior staffer, serving her third year as Editor-in-Chief. In her free time, you can probably find her hiding out in a boba cafe with her...

Meha Srivastav • Dec 3, 2016 at 12:36 pm

And I love the picture!

Meha Srivastav • Dec 3, 2016 at 12:32 pm

Touching and so important to read. Great great story Kelly! 🙂